HOME AGAIN … AND THEN WHAT ?

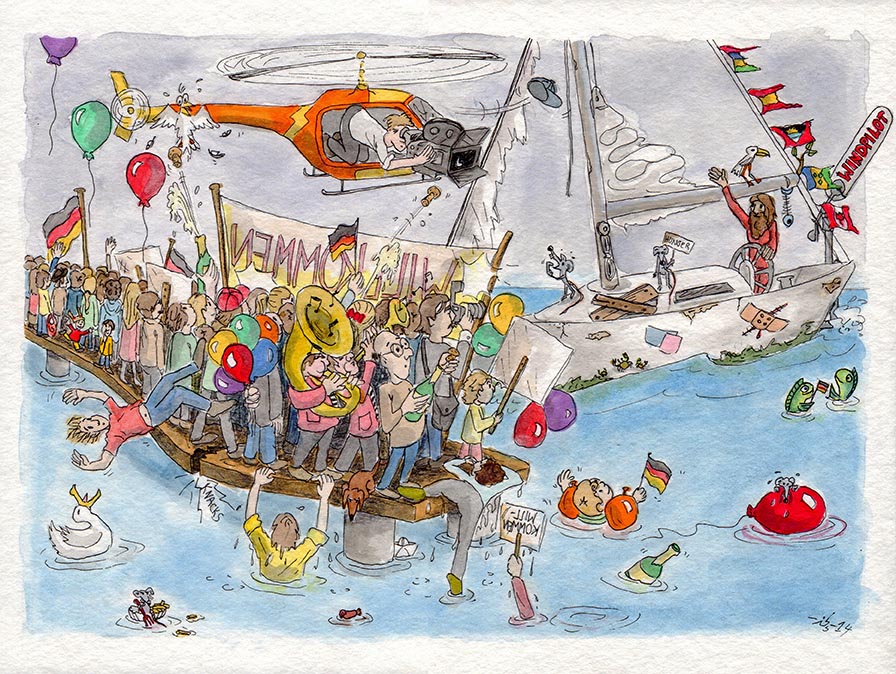

The last few miles pass in a flash and then it’s a headlong plunge into a joyous, welcoming throng of loved-ones, friends and family. Even ancient distant relations never normally to be seen anywhere near the sea make an exception and put in an appearance. There follow scattered moments of bliss, a few tears, much waving, popping of corks and draining of bottles and a fair smattering of “We must catch up properly soon”.

Family life resumes, in other words, at first probably in a kinder, gentler form with unprecedented levels of harmony and none of the usual jockeying for position: you have been gone long enough to be genuinely missed (if not forgotten). But fitting long-time absentees back into the established social structure is a process with winners and losers…

Hopes and expectations unfold against an undercurrent of reproach, a feeling that those who flew the coop voluntarily should not necessarily assume immediate and painless readmission. Mutual respect and understanding are essential if the reintegration process is to be completed without tempers flaring and those who find themselves displaced to accommodate sailors, once gone and now returned, moved to give a full and frank exposition of their feelings.

Going to sea can open a rift in the social fabric, reanimating old grievances and inspiring new ones (and some of the aggrieved will inevitably seize on the moment of return as the perfect moment to settle old scores). I am reminded once again that while our partner may be our own achievement, we have the rest of our family thrust upon us. The media may like to try and tell us otherwise (if it sells), but while most people will have no great difficulty enticing family to turn up for a party, far fewer could honestly rank their relatives among their friends.

Anyway, sooner or later the welcome party draws to a close and everyone heads home to their comfortable bed. And it is a bed – a real one with a head, a foot and two sides – and it will be comfortable; in fact thanks to our innate gift for always seeing the grass on the other side through green-tinted spectacles, even the meanest of land-based accommodation will seem positively palatial compared to the still-ever-so-slightly-damp confines of the boat.

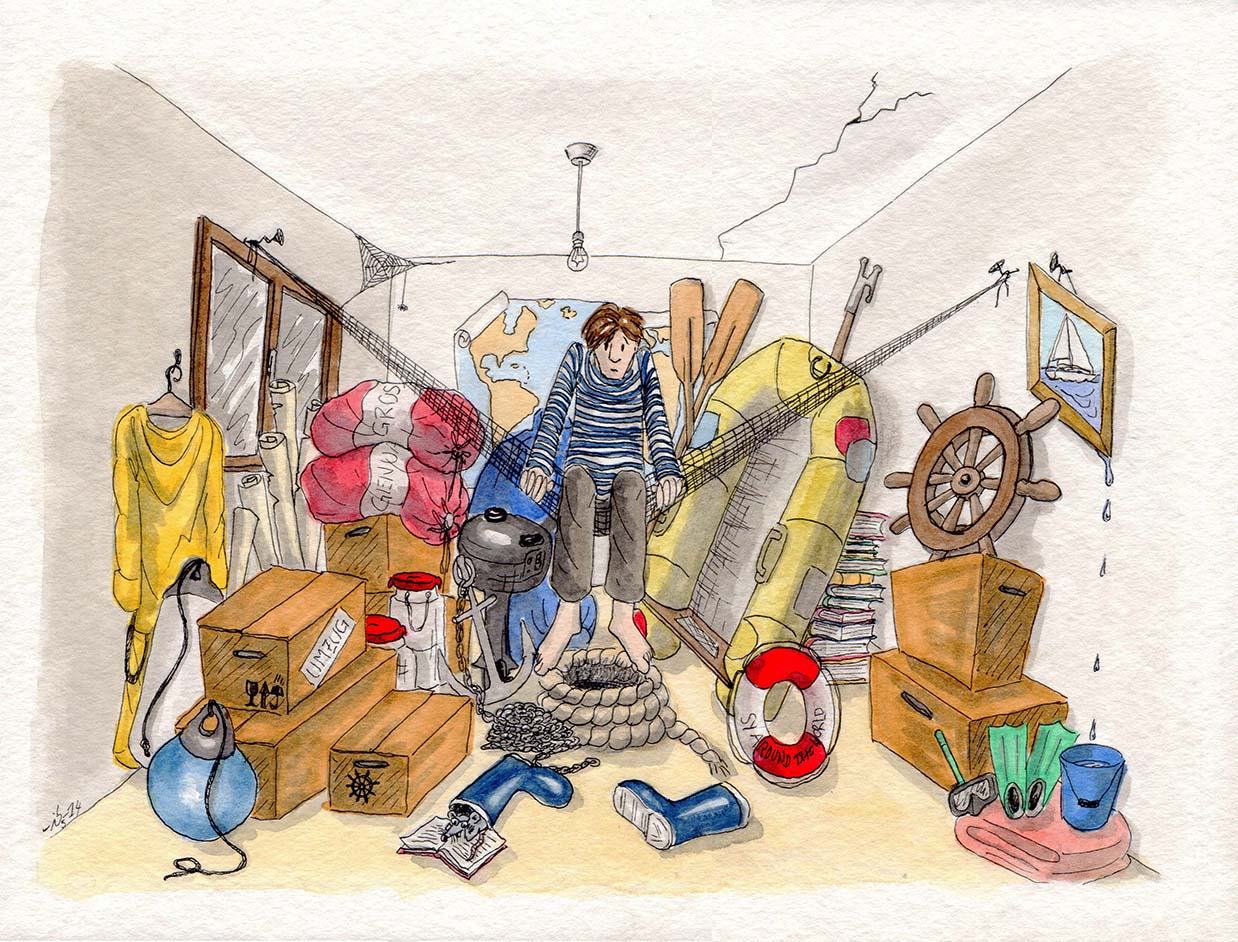

The last night on board leads directly into the enthusiastic clear-out and the ritual trial of transporting too much stuff in too few trolleys and then trying to load it into the car while still leaving space for the people. And then – drum roll please – it happens: the zero hour, tabula rasa, the first day of the rest of your life with dry land beneath your feet.

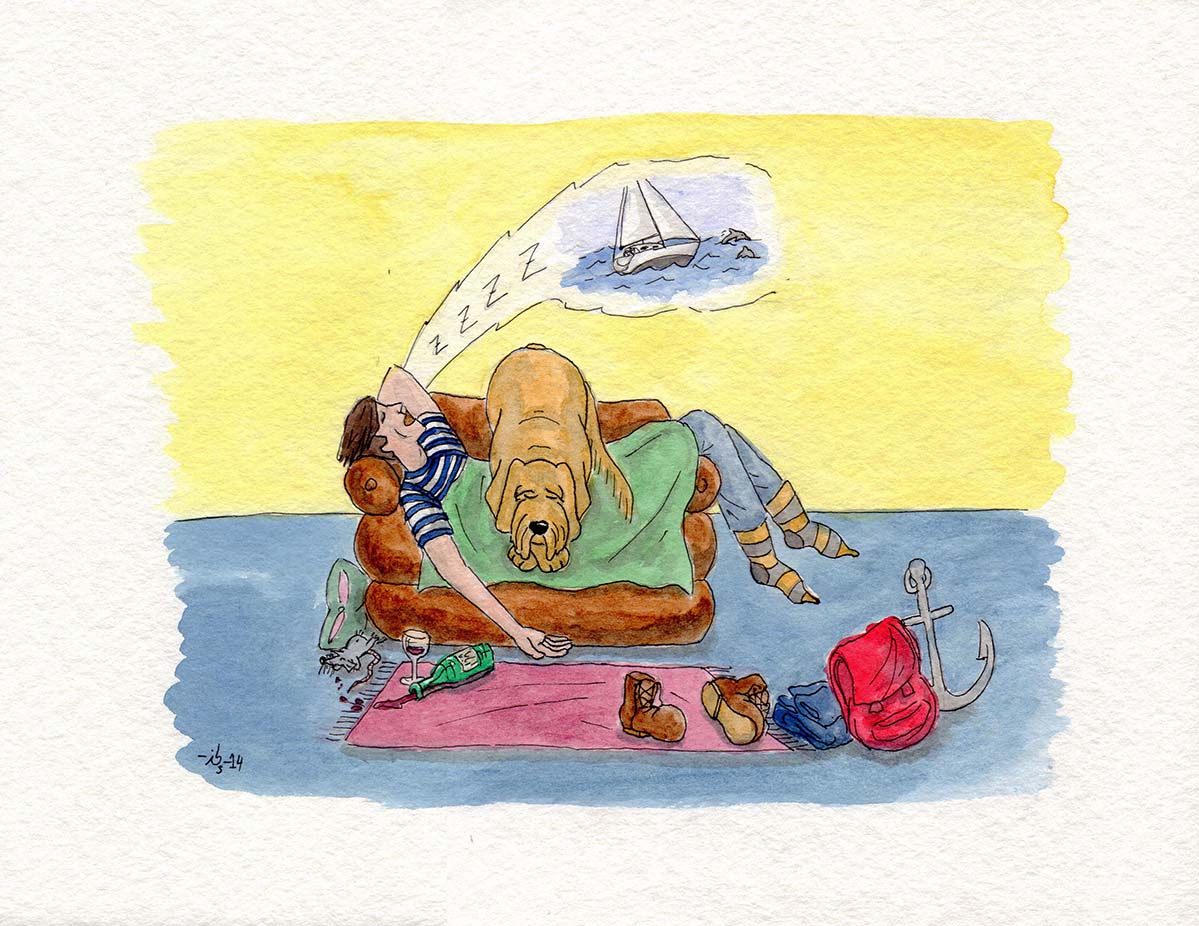

How it plays out in practice seems to depend largely on the bigger picture: some people step ashore with dreams realised and a fair idea of where to go next; others with at least mixed feelings about the past and nothing but uncharted territory ahead. The morning after the night before can be a shock without adequate mental preparation.

Those returnees who still have their own four walls have a great advantage here: dump the yachting paraphernalia somewhere out of sight, open the windows, brush off the dust, fire up the heating if necessary and boom: you are ready to go. Those who really do have to start again from scratch have it much harder: even once you have found a place to live it takes effort to turn it into home and a long time before it inspires any sense of belonging. And all the while the thought remains: down there at the waterside, tugging hopefully at its moorings, bobs the passport to an alternative future ready and waiting for another adventure.

So what next? My intention in writing this is to discuss and examine – in a hopefully humorous way and with absolutely no desire to imply any kind of value judgement – which elements of life’s rich tapestry often come to assume an unanticipated importance for the sailor returning and which have to be put out of mind for want of time to prepare properly when keeping the boat going is so much more pressing.

While every case is different and care must be taken to ensure comparisons are valid, generally speaking it makes a big difference whether the round-the-world trip takes place mid- or post-career and, of course, how much time it consumes.

STIMULUS AND RESPONSE

The causes, implications and consequences of the decision to embark on The Big One could hardly be more varied, especially as they involve and impact on whole families. Parents who decide at a relatively young age and for purely egotistical – if entirely understandable – reasons to give up a professional career that today’s uncertain labour market may well prevent them from ever resuming run a considerable risk. The risk assessments on which we base the decisions that shape our life remain sovereign territory, but the consequences of a misjudgement in this department are much more serious than they used to be. It appears more and more people are stepping ashore to find that in working life at least, resuming where they left off is simply not an option. A career break can be a significant impediment with competition for jobs so fierce, ever higher expectations with regard to personal development and qualifications and the need to demonstrate an extensive and unbroken record of professional achievement. Specialists possessed of the sort of expertise that always holds its value have a clear edge here, as they will usually be able to slot straight back into place, possibly even with the same employer. Least vulnerable of all in this context are those who have built their working life around independence, as they really can return to business as usual – provided they maintain their contacts properly while away.

Sailing around the world in the middle of working life generally involves a prolonged career break: there’s just too far to go and too much to see to manage it within a sabbatical.

Sharing the experience with children can give them a wonderful head-start in life, however. Kids usually come back thoroughly enriched by the whole adventure: more knowledgeable about the world than their peers, more skilled in communication, undaunted by change and novelty, more self-assured and decidedly more independent.

SOCIAL TIES

Long-distance sailors occupy a special position in the social web of family and friends by virtue of their itinerant lifestyle and their propensity – immune to all forms of logical or emotional persuasion – to drop off the scene for months and years on end. The decision to go, to cast off, set sail and return who knows when brings a moment of truth in family relationships, revealing how much mutual respect really exists between family members and how willing individuals are to compromise on their own desires and expectations.

The repercussions can be even stronger for parents of adult children, born, raised, schooled and graduated, who decide the hour has finally come to move on with their own life and leave their offspring to explore an independent future. The kids, accustomed to the notion that they have the old folks well trained, don’t always like the idea. Families of course can be competitive places and I am aware of several cases in which the start of the great voyage and the associated unavoidable loosening of ties proved a welcome release for all sides (in some instances with quite unforeseeable results).

We are accustomed to hearing family ties described in solemn, sacred tones but does this really reflect reality on the ground? It seems in many families that these fine words represent no more than a reflex, a habit, a borrowed collection of platitudes concealing a reality in which true solidarity remains a scarce commodity and successfully installing a respectable next generation without falling victim to any of the countless family battles to be fought along the way remains a mighty challenge. Nothing brings out the true state of family cohesion like the distribution of assets. Who sits where for dinner on the big occasions may be contentious, but it pales beside questions like who gets the house, who gets the family silver and who – whisper it gently – gets the boat. Word has reached me of families in which the parents have taken a thorough emotional beating for having the audacity to fritter away the proceeds of their life’s work on their own remaining years (afloat, naturally) without first obtaining the permission of their heirs.

The corollary of this, of course, is that there can hardly be a better way for parents to underline to the offspring that even Mum and Dad still deserve – and intend to have – a life of their own and that there comes a time when everyone needs to stand on their own two feet. The day the parents announce they’re going to sea brings a moment of truth for any family.

TIES TO HOME

All the communications wizardry in the world cannot prevent ties to home growing steadily weaker with each passing day away. Often contact is eventually lost with all but close family – and even there life goes on and the physical remoteness of sailors effectively living in a different world leaves an unmistakeable imprint. The peculiar tension between different generations habituated to living cheek by jowl ensures a steady supply of meticulously crafted reproaches. And with reproach comes guilt, that constant companion on life’s journey. Physical distance makes these barbs incomparably more effective such that sometimes brushing them aside ceases to be an option and a line in the sand has to be drawn. Nobody can outrun a constant hail of reproachful comments forever: you either take a stand or accept that eventually these verbal smart bombs will begin to take their toll. Sound defence is always the best policy!

A permanent guilty conscience does nobody any good, least of all the type of person who has probably always done their best only to discover, in later life, that their best is not good enough to spare them the reproach of dissatisfied descendants. There exists a mindset according to which the blame can always be made to lie with the other person: it’s just a case of working out why, making the accusation stick and then hoping he or she doesn’t put up a fight… People whose horizons have drawn in to nothing more than Me and Mine can be truly, truly awful.

SEPARATION AS EPIPHANY ?

Periods of separation focus attention on the essential. Everything else just fades away into the background. More than a few sailors have discovered on their return that they no longer have much to say to former friends, which perhaps begs the question: was it ever really any different? A sailing trip as the cue for an epiphany? Perfectly conceivable.

I have made the acquaintance of sailors whose address book shrank and shrank until in the end they remained in contact only with immediate family – and then only with the status of near-outlaws.

FRIENDS

A prolonged absence changes relationships even with long-standing friends. I suspect the people left behind with no grand plans of their own when a friend sets off on a great adventure often cannot help but develop a certain measure of envy. The fact that the returning mariner almost always comes home profoundly moved by the whole experience and suffused with an irrepressible urge to talk about it (in exhaustive detail) hardly smooths the waters either.

It is noticeable that sailors returning from a serious long-distance venture often go on to cultivate contacts with other well-travelled sailors, with whom they can discuss and reflect on shared experiences properly as equals, as it were, and meet with much greater understanding than can be expected with people who have never tested the bounds of their comfort zone to a comparable extent.

These friendships among apparently like-minded bluewater veterans can turn awkward though: there always seem to be a few seafaring contemporaries who consider it rather good fun to invite themselves for a visit with old “friends” and then take up residence in the guest room for as long as possible. Such problems do not arise in the same way on the water: visitors have their own home riding at anchor not so far away, so everything can be much more casual. Visits on land intrude much more fully into your own living space – your house, bathrooms and bedrooms – and expose you to much more of your guests (complete with all accompanying noises and smells). How much honesty can a person bear in these circumstances? My wife has devised her own simple rule: after three hours fish and visits begin to impinge on the nose, personal freedom begins to feel constrained and attentive curiosity begins to wane. Sensitive and considerate visitors, of course, are a different matter. Mutual respect can quickly be established if people have the confidence to speak their mind. Politeness is one thing, but nobody has any fun if everyone feels they are walking on eggshells.

IN SUMMARY

Partners who have survived sailing around the world together are ideally prepared to share whatever challenges the rest of life has in store for them: there is precious little on land capable of shaking foundations that have withstood the trials of a life at sea.

Circumnavigating amicably with a partner as a team of two is an intense experience that creates a tight bond between the couple involved while simultaneously distancing them from those left ashore. Time at sea infuses a sense of perspective not always appreciated or understood by uninitiated friends and relatives, who may be found to seek solace in jealousy.

Still, we cannot hope to please everyone all the time so perhaps a little more realism is in order: manage to be happy in your own skin and a large part of the battle is already won…

suggests

Peter Foerthmann