SEAWEED – FLOTSAM – THINGS THAT GO BUMP IN THE SEA

Sailing would be much easier and safer if all we had to worry about was the water. Usually it is when the water runs out – or when something solid goes to sea without sinking – that the trouble begins. Flotsam, fishing lines, entire shredded nets held aloft by floats, assorted rubbish, old mattresses and, of course, the occasional shipping container that has rudely hopped overboard … All are lurking out there somewhere, barely visible (if at all), waiting to snuggle up to some unsuspecting hull or appendage. Only the fortunate ever cover significant distances at sea without having ridiculous encounters of this kind to report. Or is there more to it than good fortune? Let us investigate.

Sailing would be much easier and safer if all we had to worry about was the water. Usually it is when the water runs out – or when something solid goes to sea without sinking – that the trouble begins. Flotsam, fishing lines, entire shredded nets held aloft by floats, assorted rubbish, old mattresses and, of course, the occasional shipping container that has rudely hopped overboard … All are lurking out there somewhere, barely visible (if at all), waiting to snuggle up to some unsuspecting hull or appendage. Only the fortunate ever cover significant distances at sea without having ridiculous encounters of this kind to report. Or is there more to it than good fortune? Let us investigate.

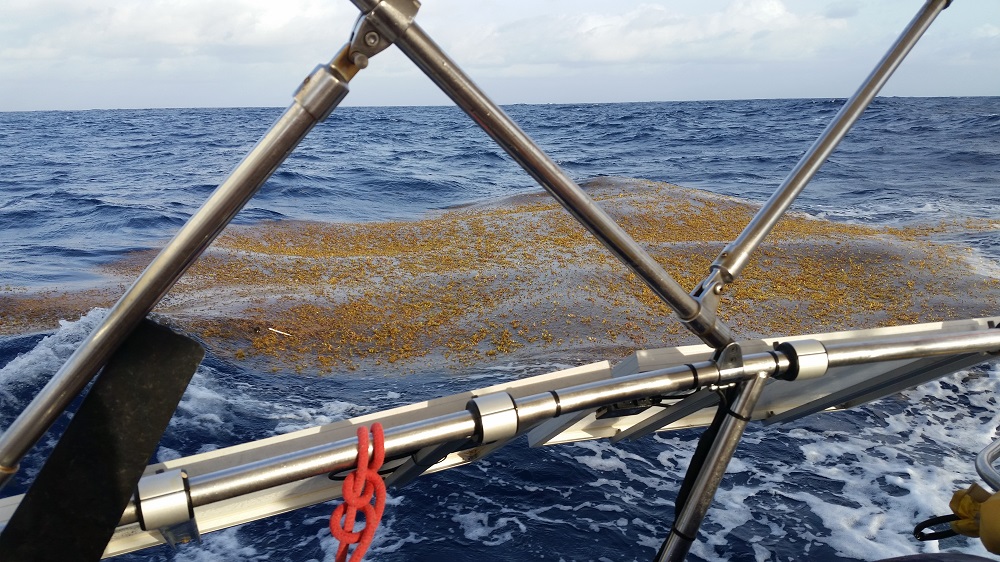

None of what I am about to write should come as any great shock to the thinking sailor: if we are honest about what we know about our boats and the sea we sail them on, my conclusions are essentially self-evident. Certainly there can be nothing controversial about my pointing out that a boat with a long keel will sail through or over almost anything that isn’t attached to the earth with no dramas, often without the crew on deck or in their bunks knowing anything about it. That long keel just pushes everything aside or deeper down into the water out of harm’s way. Long-distance passage-making in a modern boat, in contrast, involves all kinds of worrying what-ifs to consider – and try to prepare for as far as possible. Look below the waterline of a modern design and there are likely snagging points everywhere, perfectly poised to sweep up their share of the millions of tonnes of junk that drifts endlessly around the continents. As if that were not enough, nature has stepped up the production of free-floating seaweed in recent years too: now sailors in many waters have to be on their guard for appendage-hugging vegetables on top of everything else.

None of what I am about to write should come as any great shock to the thinking sailor: if we are honest about what we know about our boats and the sea we sail them on, my conclusions are essentially self-evident. Certainly there can be nothing controversial about my pointing out that a boat with a long keel will sail through or over almost anything that isn’t attached to the earth with no dramas, often without the crew on deck or in their bunks knowing anything about it. That long keel just pushes everything aside or deeper down into the water out of harm’s way. Long-distance passage-making in a modern boat, in contrast, involves all kinds of worrying what-ifs to consider – and try to prepare for as far as possible. Look below the waterline of a modern design and there are likely snagging points everywhere, perfectly poised to sweep up their share of the millions of tonnes of junk that drifts endlessly around the continents. As if that were not enough, nature has stepped up the production of free-floating seaweed in recent years too: now sailors in many waters have to be on their guard for appendage-hugging vegetables on top of everything else.

So much for the obstacles; what about the Achilles’ heels that make certain boats particularly susceptible? Some we have covered already:

What else ought we to consider?

A long keel (did I mention how useful a long keel can be?) will generally provide very good protection for the extremities in its wake. Not every underwater component of the boat lines up with the keel, of course, and anything that protrudes from the hull away from this protected central zone stands alone and exposed. This includes the rudders in twin-rudder configurations, assuming both are in the water.

The sharp minds in the IMOCA fleet adopted modular lifting rudders a long time ago, enabling them to replace the blade relatively easily (relative, that is, to verging on the impossible) after a collision with flotsam (as well as allowing them to have the windward rudder flying in the breeze when it suits them). Many of the IMOCAs even incorporate a pop-up mechanism that allows the rudder to swing up aft on impact and thus – hopefully – avoid damage.

None of that has any relevance for the dedicated long-distance cruiser though, as solutions of this nature cost far too much to be a possibility for production leisure yachts. Boats sporting twin rudders but just the one keel thus have an additional Achilles’ heel not just because they have twice as many rudders scouring the ocean but because neither of those rudders gains any protection from the keel. The following clip provides an insight into the pain that can ensue.

None of that has any relevance for the dedicated long-distance cruiser though, as solutions of this nature cost far too much to be a possibility for production leisure yachts. Boats sporting twin rudders but just the one keel thus have an additional Achilles’ heel not just because they have twice as many rudders scouring the ocean but because neither of those rudders gains any protection from the keel. The following clip provides an insight into the pain that can ensue.

It would be remiss of me not to point out that windvane self-steering systems installed off-centre face exactly the same hazards. Collisions with flotsam place unbelievably high loads on the gear’s mounting components. If they or the gear itself fail, that is the end of silent self-steering. If they pull out of the transom, that may well be the end of the boat (as seems likely to have happened in the case of the German-flagged Hanse 388 Plan B). I should also mention that the transom on almost all modern production boats is not designed or built to endure such high loads. The manufacturer of the Hydrovane wisely recommends reinforcing the inside of the transom on a grand scale to ensure it is strong enough to cope with the very substantial loads generated by an auxiliary rudder system even for simple steering movements.

It would be remiss of me not to point out that windvane self-steering systems installed off-centre face exactly the same hazards. Collisions with flotsam place unbelievably high loads on the gear’s mounting components. If they or the gear itself fail, that is the end of silent self-steering. If they pull out of the transom, that may well be the end of the boat (as seems likely to have happened in the case of the German-flagged Hanse 388 Plan B). I should also mention that the transom on almost all modern production boats is not designed or built to endure such high loads. The manufacturer of the Hydrovane wisely recommends reinforcing the inside of the transom on a grand scale to ensure it is strong enough to cope with the very substantial loads generated by an auxiliary rudder system even for simple steering movements.

Keeping watch for huge mats of floating seaweed has now become part of the daily routine for sailors in many parts of the world. Collecting seaweed on the appendages is slow, slow slow and having to dive regularly to remove it quickly becomes a chore.

Almost every time I see a balanced rudder and that narrow gap between the bottom of the hull or skeg and the top of the blade, my mind turns to thoughts of how easily seaweed, plastic bags, old rope and other unwanted passengers of that ilk can lodge there and disable the steering. My Hanseat always had a triangular metal deflector in front of this gap to reduce the chance of bad things happening.

Almost every time I see a balanced rudder and that narrow gap between the bottom of the hull or skeg and the top of the blade, my mind turns to thoughts of how easily seaweed, plastic bags, old rope and other unwanted passengers of that ilk can lodge there and disable the steering. My Hanseat always had a triangular metal deflector in front of this gap to reduce the chance of bad things happening.

Darum gilt mein besonderes Augenmerk seit Jahrzehnten den Balancerudern, deren Vorkante dicht unter dem Rumpf einen Spalt besitzen, der als Rattenfänger für Unrat, Leinen und Seegras irgendwann das ganz Ruder ausser Kraft zu setzen in der Lage ist. Auf meinen Hanseaten war zur Entschärfung dieser Gefahrenstelle stets der Schlitz durch einen dreieckigen Abweiser in Form eines Knotenbleches “entschärft”.

Darum gilt mein besonderes Augenmerk seit Jahrzehnten den Balancerudern, deren Vorkante dicht unter dem Rumpf einen Spalt besitzen, der als Rattenfänger für Unrat, Leinen und Seegras irgendwann das ganz Ruder ausser Kraft zu setzen in der Lage ist. Auf meinen Hanseaten war zur Entschärfung dieser Gefahrenstelle stets der Schlitz durch einen dreieckigen Abweiser in Form eines Knotenbleches “entschärft”.

I learned of the following on theCruisersforum ist folgende Begebenheit:

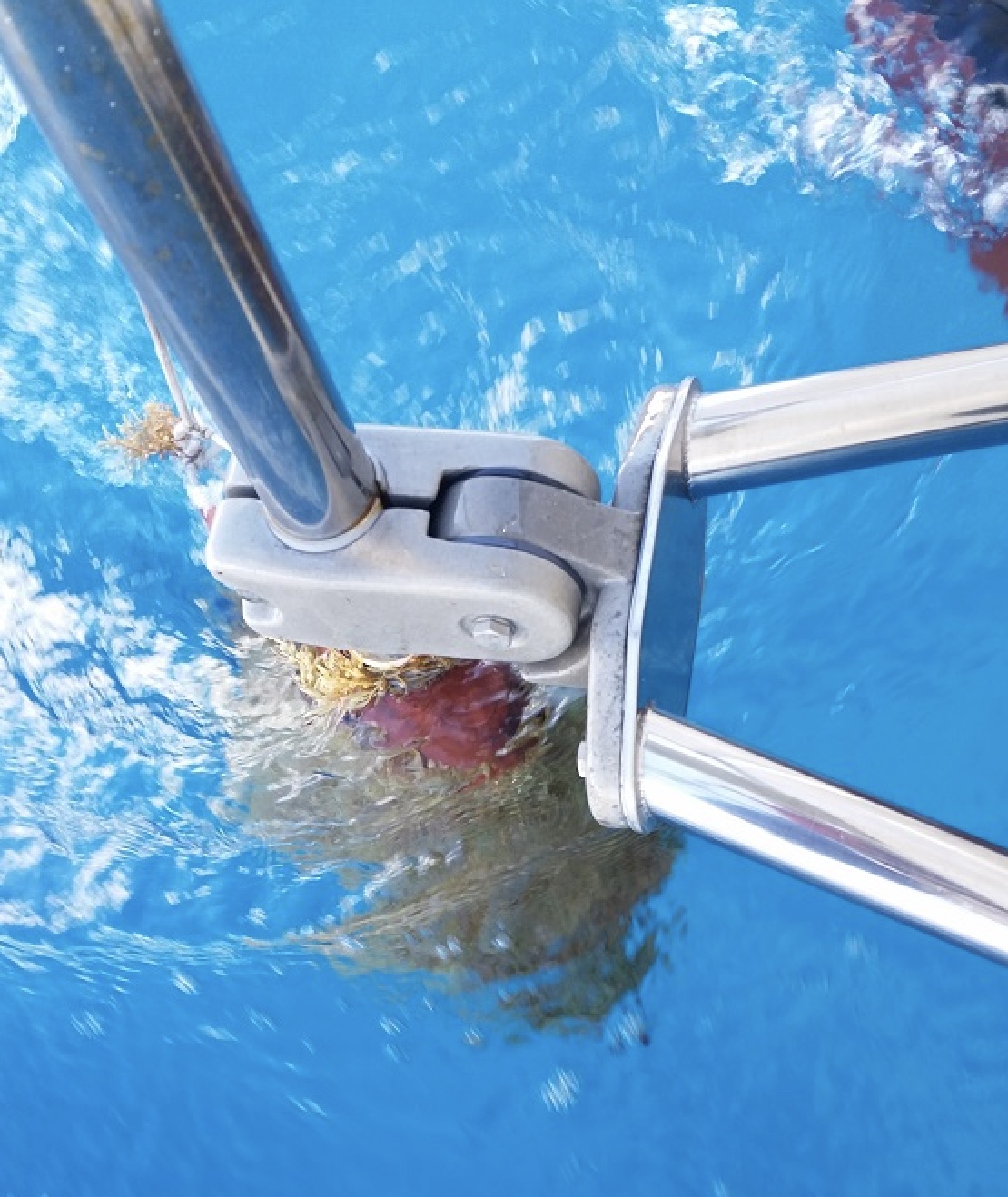

We have a Hydrovane on our boat and have found it to catch sargassum weed in such a degree that it no longer can steer the boat.

When crossing the Atlantic in 2017 we at times had to clean it every 5 minutes.

It is so frustrating when you sail around the clock and you have to be on the alert for this type of problem. We are a short handed crew and need all the rest we can get. It has happen more than once that the boat has taken a tack by herself when the vane is out of control. It’s worse if you sail with a gennacker. Then it can take some time before you get back on track.

I find this unacceptable. It is dangerous hanging over the side trying to free the rudder from the sargassum weed. You risk breaking a rib or two or falling over board, sails may get damaged and you are deprived of the rest you so badly need.

I have explained this to John at Hydrovane and suggested they would redesign the rudder with a taperd leading edge so that the grass will travel down and under but they seem not interested in doing anything to rectify the problem.

I realise that a redesign may not be a simple task and would certainly need thorough testing but this problem is not going to disappear. It will probably get worse.

I have talked to a number of people with Hydrovane’s and I am not alone having trouble with weed.

Our vane is mounted off centre, which is one of the key features according to the Hydrovane home page. It may be a less of a problem with centre mounted since you then have the keel and the rudder in front to clear the way for the wind rudder.

Are there others out there with the same problem and if so did you have a remedy to get the gear working when confronted with this weed ?

/Hans

Servo-pendulum systems with the rudder shaft angled aft slightly and a friction coupling that allows the pendulum rudder blade to kick up on impact with flotsam are inherently better protected … although how useful this is depends to a fair extent on whether they can be reset easily by hand. There is no chance of the crew failing to notice the blade has kicked up either because self-steering ceases as soon the blade leaves the water. Even the heaviest sleepers will struggle to ignore the sound of flapping sails.

Servo-pendulum systems with the rudder shaft angled aft slightly and a friction coupling that allows the pendulum rudder blade to kick up on impact with flotsam are inherently better protected … although how useful this is depends to a fair extent on whether they can be reset easily by hand. There is no chance of the crew failing to notice the blade has kicked up either because self-steering ceases as soon the blade leaves the water. Even the heaviest sleepers will struggle to ignore the sound of flapping sails.

Choosing a boat involves trade-offs and compromises, the implications of which sailors should do their utmost to understand. This too will come as news to nobody who sails! Choosing a windvane self-steering system also involves compromises, but I feel very strongly – and have been arguing for years – that mounting the system off-centre is a compromise too far. I do appreciate that advocates of the swim ladder and bathing platform can make a very strong case for accommodating the vanegear off to one side and that some consider this perfectly acceptable. This decision comes with consequences though and I believe it only fair to point them out.

Choosing a boat involves trade-offs and compromises, the implications of which sailors should do their utmost to understand. This too will come as news to nobody who sails! Choosing a windvane self-steering system also involves compromises, but I feel very strongly – and have been arguing for years – that mounting the system off-centre is a compromise too far. I do appreciate that advocates of the swim ladder and bathing platform can make a very strong case for accommodating the vanegear off to one side and that some consider this perfectly acceptable. This decision comes with consequences though and I believe it only fair to point them out.

Choices, choices. There are arguments to be made on both sides and in the end the only sure answer is compromise – but not compromised.

Here ends my thought for the day this Sunday evening.

25.04.2021

Peter Foerthmann