How to hear and be heard with marine radio

We, the honorary operators of marine radio networks, rely heavily on good communication with sailing boats, so I would like to take this opportunity to offer some advice and tips on the subject of installing and operating marine radio transceivers.

We, the honorary operators of marine radio networks, rely heavily on good communication with sailing boats, so I would like to take this opportunity to offer some advice and tips on the subject of installing and operating marine radio transceivers.

Good technology can make a big difference, but what use is even the best radio set if it is not installed and cared for properly? And remember: WINLINK and SAILMAIL too can only work smoothly if the ship’s radio is firing on all cylinders.

Conditions for the propagation of radio waves are steadily deteriorating, making proper transceiver installation more important than ever. Radio problems at sea can be more than just an inconvenience: if nobody can hear your distress signals, nobody will come to your aid. Fortunately it is perfectly possible to install your radio properly yourself even if you do not happen to be an electrical engineer or radio ham. The main thing is to read the manuals supplied by the receiver and antenna tuner manufacturers particularly carefully to make sure you understand fully the points they are trying to make in their instructions and recommendations.

You should be aware that some of what you read in these instructions and recommendations will run counter to the advice of certain bluewater veterans – the reason being that the latter have still to grasp that with most users now preferring other means of communication, there is actually very little radio traffic at sea these days.

Today yachts really have to rely on SAILMAIL or WINLINK to keep in touch and it consequently makes sense when looking for a new radio to concentrate from the outset on systems that allow full frequency scanning rather than being limited to programmed frequencies.

Manually operated radio sets are more favourably priced and easier to use. For more detailed advice, an amateur radio enthusiast is always going to be a better bet than a dealer in a hurry to sell you a particular marine system.

All sailors with bluewater ambitions would do well to NOTE that systems targeted at amateur radio operators have a memory capable of storing up to 100 frequencies, which means you can easily add all of the required marine channels including the PACTOR frequencies. These systems also handle sudden frequency changes better than marine radios, which have to be reprogrammed every time, and are of course much better when it comes to finding someone to talk to.

THE COSTS

An amateur radio transceiver should cost no more than EUR 600-900, while suitable antenna tuners come in at around EUR 450. As for accessories, wiring, connectors, coaxial cable etc. should not add up to more than EUR 50.

The total cost (assuming free labour – installing all of the components will generally take two people about four hours) should thus amount to somewhere in the region of EUR 1,400. This compares very favourably with typical marine radio transceivers, which cost around EUR 1,700 excluding accessories despite offering less functionality than an amateur radio system.

THE RADIO SYSTEM

A radio system typically comprises

– an antenna

– a tuner

– a transceiver (what we conventionally call the radio) and

– the cables required to hook it all together.

THE ANTENNA

is the most important component of a radio system. It consists of

– an insulated backstay or

– a vertical whip antenna.

THE TUNER

adjusts the endless antenna to the frequencies required by the transceiver using relays, whose coils shrink or extend the antenna according to frequency.

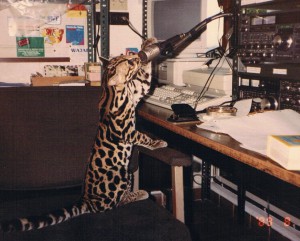

THE TRANSCEIVER (‘RADIO’)

first checks that the antenna is tuned to the selected frequency and reduces the output power selected where necessary if the antenna is not properly tuned. While antenna tuning problems can have numerous causes, wrongly installed or corroded connectors are the culprit in a good 90 percent of cases. The output power of the transceiver has to be reduced considerably in the event of poor tuning in order to prevent possible damage to the output stage.

THE CABLES

join the other components together. Their job is to conduct signals between the antenna, the tuner and the transceiver as cleanly as possible. Cables are critical for good radio performance, so it is vital to avoid any shortcuts in this area: use only top-quality materials and ensure they are installed (connected, soldered etc.) with care. Top-notch cables will only cost you EUR 10 or so more than some very average equivalents, a difference out of all proportion to the grief you stand to avoid.

THE COMPONENTS IN DETAIL

ANTENNAS

BACKSTAY ANTENNAS

ideally need to have the antenna feedpoint positioned on deck as close to the backstay as possible so that the tuner can be installed close by but still protected below deck. Some tuners are built to be installed in the wet on deck, but even these are probably better safely tucked away down below.

Some backstay antennas are isolated at a height of two to three meters above deck. If you have one of these, the tuner should be mounted on the backstay at this same height. The length of the coaxial cable connecting the radio is not particularly important, as losses here are very low: anything up to 20 meters should be no problem at all. It is important, however, to make sure the coaxial cable is sufficiently thick: never use RG58 cable!

NOTE that the tuner and antenna feedpoint should never be more than 30 cm apart. Do not be misled by boat-builders telling you the backstay needs to be isolated well above deck level because of the risk to the crew of electric shock when transmitting: it is very easy to insulate a live backstay over the area likely to be touched.

WHIP/ROD ANTENNA

A whip or rod antenna should be 6.10 metres long and should be mounted on the stern inclined at an angle of 10° aft.

This type is preferable to a backstay antenna because it provides more conducive conditions for good radio performance. It stands much closer to vertical than the backstay, meaning that much less of the signal transmitted goes straight down into the sea or up into sky, and the antenna feedpoint is at deck level, so the distance between tuner and antenna can easily be kept short (it is best to limit this distance to 30 cm or less – while distances of up to a metre may be acceptable in a few exceptional cases, anything more is quite out of the question).

Installing a whip antenna is inexpensive and makes an easy DIY job for the average boat owner.

WESTMARINEcarries Shakespeare brand antennas with a mount designed to allow central or offset installation on the stern.

SMART, ICOM, KENWOOD, YAESU etc. all recommend that the antenna – whip or backstay – be no more than 30 cm from the tuner. All sailors would do well to commit this advice to memory: the manufacturers know what they are talking about!

TRANSCEIVER

All branded amateur radio systems are suitable for use afloat. What matters is the quality of the installation work and the materials employed.

CABLES

The cables linking the antenna and tuner should be insulated copper wire with a core diameter of at least 6 mm. This stiff cable tends to keep its shape well, which is useful where it has to be led along a specific course in order to keep it well away from metal components of the boat. The cable forms an extension of the antenna and should as far as possible be led to the tuner directly with no unnecessary turns.

EARTHING

The earth wire, which should be a copper cable of no smaller diameter than the antenna/tuner cable, should run directly from the tuner to a good earth. The distance between the tuner and the earth should be as short as possible.

There are many different theories concerning earthing on yachts and this is not a debate to be entered into lightly. There does, however, seem to be substantial agreement that the best solution involves running copper cables in all directions throughout the boat. Earthing using what are known as earth radials provides a perfect counterpoise for the antenna.

TUNER CONTROL CABLE

The tuner control cable connects the tuner to the radio. It is usually supplied with the tuner, but can be extended. Be sure to follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

COAXIAL CABLE

can be of virtually any length – see above for size. I recommend Belden cables.

CONNECTORS

Always choose high-quality connectors. I recommend Amphenol connectors. The difference in price between really good connectors and less impressive equivalents (such as some from Taiwan) is relatively small, but the difference in quality is huge: just look at the discrepancy in heat resistance and the finish of the internal insulation.

ANTENNA TO TUNER CABLE

This needs to be an insulated battery cable of no more than 30 cm in length with a core diameter of at least 6 mm. The first 5-6 cm (at least) of insulation at the antenna end is removed and the entire length of wire thus exposed is then soldered into place.

The tuner end of the cable is fitted with a lug that matches the post on the tuner. Note that the cable lug must be soldered on across the whole of its surface to ensure that all of the wires are joined.

All connections should always be kept clean and grease-free.

The cable linking the antenna to the tuner should be installed so that there is a 5 cm loop of cable pointing upwards immediately above the connection to the backstay. This short loop, which represents a simple yet effective way of preventing water penetrating into the insulation, should be secured with two band clamps. NOTE that a larger contact area means better conductance.

Seal the quick-connect terminal with silicone once you have tested your transceiver.

NOTE that a minimum distance of approximately 8 cm should be maintained on all sides between the cable and any metal components of the boat. The point at which the cable passes through the deck must be very well insulated on steel yachts.

Manufacturers stipulate how the cable is to be connected to the tuner (usually with a wing/thumb screw). This spot can also be protected with silicone after testing the system, especially if the tuner is being installed in a wet area.

It is best always to leave the drain screw on the tuner slightly open so that any condensation can escape.

TUNER EARTH

The tuner should be connected to a good earth with coaxial cable (see tuner/radio connection). It is not necessary to earth the radio itself, because it is already earthed through the tuner and double earthing is not necessarily a good thing.

TUNER CONTROL CABLE

The partially live control cable is supplied with the tuner. Different products have different requirements, but the basic rule – as usual – is to connect strictly according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ANTENNA – TUNER – TRANSCEIVER CONNECTION

Coaxial connectors must be soldered across the whole contact surface: poor connections here are the most likely cause of a poor signal. The coaxial cable’s copper braid shield conductor should be made available evenly along the full length of the exposed cable by carefully soldering the individual wires together. Coaxial cable becomes unusable if a black deposit forms on the braid and/or if individual wires are not soldered in unless the actual ends are soldered together, in which case all wires make contact in the required area.

Be sure to use 50 Ohm RG-H 8 coaxial cable. In fact this recommendation also goes for all other electrical cable on board.

NOTE:

– Never use graphite grease or other greases on cable connections.

– Use a professional-standard soldering iron (at least 300-400 W) for all soldering work (connections soldered at an inadequate temperature are the most common cause of subsequent faults in the radio system).

Good materials properly installed and carefully soldered should ensure many years of trouble-free communication with other stations both ashore and afloat.

CHECKING THE RADIO SYSTEM

Check the antenna system as follows after installation and before every broadcast:

1. Switch on the transceiver.

2. Set the required frequency.

3. Select any transmitting power.

4. Press the Tune button to set the tuner to this frequency.

5. Press the transmit button and verify the output power with a loud noise or whistle.

If the output power is less than 60% of your selected power, you know that one of your connections is not right.

TROUBLESHOOTING

starts with the antenna – tuner – radio link.

Any white deposits on the connections should be cleaned off with a wire brush.

Poor signals on sailing boats are in fact almost always the result of defective or excessively long cable links. It seems all wrong that such obvious problems can have such a big impact, but they do: from my home here in Panama, for example, I can receive transmissions from yachts in Malaysia perfectly and yet struggle to read others that are just 2,000 miles away.

WORTH KNOWING

High-frequency currents associated with radio use are the most common cause of all kinds of electrical disturbance on board including problems with electric autopilots, LED displays, radar and even lights, but few appreciate how easy the solution can be. Just attach split-core ferrite beads of the right size for your cable to the coaxial cable close to where it enters the radio to damp the HF currents permanently: never again need you stand in the cockpit in the rain steering because the autopilot takes exception to other members of the crew chewing the fat on the radio.

Life afloat can really be that simple…

Hallo Herr Hamacher,

danke für Ihre Zusammenstellung hier im Blog. Wir haben vor kurzem ein kleines Boot gekauft. Eine Contessa 32. Sie kommt demnächst zu kleinen Refitarbeiten in eine Werft. Seit einiger Zeit habe ich mir vorgenommen eine Amateurfunklizenz zu erwerben. Bin auch Mitglied im DARC. Aus zeitlichen Gründen habe ich meinen “Fernkurs” derzeit unterbrochen. Die Lizenz mache ich ausschließlich im Hinblick auf die Segelei. Auf dem Boot soll zu gegebener Zeit dann eine entsprechende Anlage installiert werden. Meine Frage an Sie ist, ob während des jetzigen Werftaufenthaltes Vorbereitungen dafür getroffen werden können. Z.B. hinsichtlich der Erdung oder der Antenneninstallation. In einem Reisebericht von “Hippopotamus” habe ich gelesen, dass eine großflächige Erdung mit Hilfe zeiner Kupferfolie oder eines Antriches erfolgt ist. Ebenso liest man immer wieder, dass das Achterstag eine rel gute Antenne ist. Viele Fragen, aber jetzt gehts erstmal um die Basics. Vielleicht haben Sie Lust mir ein paar Tipps zu geben oder evtl auch Ansprechpartner hier in Deutschland, die sich mit Amateurfunk auf Segelyachten gut auskennen.

Gruß

Roland Brokmann

Witten an der Ruhr

Hallo Guenter Hamacher!

Mit grossem Interesse habe ich Deinen Blog gelesen und werde beim noch zu machenden Anschluss des Geraetes ICOM 710 with AT130 tuner auf dem gerade gekauften und noch nicht uebernommenen Schiff (siehe obige Seite) davon profitieren.

Aufgrund der Backstay Situation (siehe Bilder) moechte ich Deiner Empfehlung fuer eine Whip Antenne folgen. Passt zu dem Ganzen das neue Pactor IV? Bin noch totaler HAM Laie, hab zwar eine HAM Lizenz hier in NZ gemacht, jedoch noch nie von eigener Anlage gefunkt! Wird sich aendern. Call Sign ZL2ICU. Also extremer Anfaenger Amateur!! Werde Hilfe brauchen und schaetzen! Bin fuer alle Tips sehr dankbar! Wollte eigentlich ein HAM Radio anschaffen, aber das ICOM ist schon da und neu. Wie die Anlage verbaut und geerdet ist, habe ich noch nicht gesehen.

Viele Gruesse aus NZ

Sepp