LIBERTÉ, EGALITÉ, FRATERNITÉ – or none of the above?

Freedom, equality and fraternity: values that inspired the rebirth of a nation but whose lustre seems to have faded under the onslaught of individualism, values that may or may not, depending on one’s viewpoint, have contributed to the emergence of a very particular – that is to say very particularly French – way of dealing with life, other people and the world in general.

Savoir-vivre is a concept that invites conflicting interpretations: the knowledge required to fit in effectively, for example, or an outline of where the ultimate boundaries lie in a sphere in which the individual, unswayed by the (will of) the larger whole, stands above all things.

My first opportunity for a taste of France came in 1970, when I drove to Paris in – fittingly – a swish Peugeot 404. I unsuspectingly parked in a church car park in the Latin Quarter and set off to continue my travels with the metro. Quel dommage: when I returned a few days later my poor car had sustained quite a collection of scratches and dents and to my great dismay nobody around seemed to have any idea what could possibly have happened.

I have spent a great deal of time in France and with the French over the intervening years and my overriding impression is that despite incessant socialisation, these are a people among whom individualism and the individual will have managed to bloom remarkably prolifically, at times in ways outsiders find hard to comprehend. A drive through Paris suffices to give a fair impression of the practical implications: when traffic lights appear to operate in a purely advisory capacity, the sight of six cars side-by-side on a three-lane road is nothing out of the ordinary, undersized parking spaces are quickly brought up to the mark by giving the cars in front and behind a nudge and the loss of a wing mirror in a collision passes almost without notice, a responsible German motorist like me cannot help but realise that it is not merely their laissez-faire attitude to automobiles that sets the French apart.

Exhibiting at French boat shows gave me the opportunity to enhance my understanding. I found myself learning:

– that the French really like to smoke, preferably while discussing self-steering, the ash steadily accumulating on my carpet to be followed, soon enough, by the glowing remnants and the grinding sole of an extinguishing shoe (my floor covering always ended up full of holes and went straight in a skip at the end of the show);

– that the French prefer to speak only French even when they are quite capable of speaking English (forget this golden rule and you face a lonely and isolated existence unless you are fortunate enough to meet one of the few exceptions, who are about as common as mermaid scales);

– that French officials, which in my case means boat show organisers, are utterly ruthless, at least when it comes to what exhibitors have to pay and what they can expect in return (several hundred euros for a parking space that has been sold twice and hence might as well not exist, cheeky mark-ups for providing a power outlet, sanitary facilities … and the pièce de résistance, an exhibition centre located below the Périphérique, the plentiful exhaust fumes from which provide the air supply for anything respiring in the exhibition halls); and

– that French boat show organisers like to conceal their own shortcomings behind a blizzard of rules and forms (exhibitors are required, for example, to sign a written undertaking to ensure replacements are provided to staff their stand in the event of even the shortest of absences – lunch or a call of nature, for example).

Freedom never tasted sweeter than the day after the Paris show. The fact that the Salon Nautique always required a twelve-day commitment (set up on the Wednesday, last day two Mondays later) didn’t help either. Officially these timings were described as a measure to avoid unnecessary traffic congestion, in which case why hold four different events concurrently at the same exhibition complex? I suspect the thing that concerned them most was the possibility of having the horses from the Salon du Cheval de Paris getting loose and bolting through the boat show. Chacun son goût, they say, each to their own. Which is fine on the whole, but the extremes to which individualism is taken at times in France can defy the understanding of a properly house-trained German visitor.

WHAT MAKES THEM TICK

Not surprisingly, French sailors too have their own particular way of doing things and it is the whys and implications of this observation that the present blog sets out to explore.

The first point to make is that France, to its enormous credit, respects sailing as a sport of the utmost national importance – to the extent that even the nation’s couch potatoes have time for sails as well as the miserable round leather ball. When I travelled to Les Sables d’Olonne in November 1989 to watch the start of the first Vendée Globe race, it didn’t take me long at all to understand why, despite the cold, damp and altogether unwelcoming weather typical for the time of year, every bed in the town was booked and why I was just one of hundreds to be spending the night sleeping in my car by the beach. Even then le Grand Départ had the air of a public festival and the bay was heaving. The eventual winner, Titouan Lamazou, celebrated his victory by being driven/carried down the Champs Elysée. Such things would be quite unthinkable in Germany, a nation with completely different priorities in which sailing has never commanded – and in all likelihood never will command – the attention even of the back pages, never mind the front page.

Sailing is big business in France. All of the major national and international regattas and events enjoy serious commercial backing and it is entirely de rigueur for major brands to have their name plastered all over the latest offshore flyers. The combined expertise and experience of designers, builders and skippers in collaboration with the combined financial strength of major companies has elevated France to the status of sailing powerhouse.

French sailors dominate offshore sailing to such an extent that it is difficult to see them ever being overhauled – and the nation as a whole follows, understands and appreciates their achievements. Will I ever see the sport of sailing scale such heights in the German media? Most Germans have no enthusiasm for sailing and there is no reason to expect that to change, so the answer has to be no. And of course a lack of media interest means an equally pronounced lack of interest among potential sponsors.

LARGE OR SMALL?

Run a critical eye over French marinas and it soon becomes apparent that the common sailor has little capital spare to invest in his or her favourite sport. The number of small, even tiny, boats is striking and it speaks volumes for the ability and experience of ordinary French sailors that having little more than a nutshell between themselves and the brine in no way discourages them from traversing even the most challenging of waters.

The uniqueness of the French market is underlined by the existence of a number of affiliated associations Unité Amateur de Francecreated for the specific purpose of helping their members design and build their own boats. They cover the entire country and have thousands of active members, giving them not only a huge resource of technical expertise, but also purchasing power on a scale that has enabled them to negotiate highly favourable terms with suppliers. A typical sales consultation on French boat show stands regularly ends with an enquiry about the special discount available for UA members. Unfortunately I have to report that the UA have apparently seen quite a number of scandals over the decades too, most of them involving association employees trying to line their own pockets. But then again filthy lucre has a strong allure all over: even France is no different in this particular respect.

An enormous range of different amateur designs have been built and launched in France over the years. Steel remained the self-builder’s material of choice for decades, with most designs adopting a multi-chine approach with lifting keel or centreboard. One of the best-known design teams in this category is Caroff-Duflos Naval Architects, which remains very active and is held in the very highest regard among bluewater sailors.

French boatbuilders have been using aluminium, especially seawater-resistant AlMg4.5mn, for decades. Legendary French company GOIOT has been manufacturing winches, hatch covers and deck fittings in AlMg5 for over 50 years and yet foundries in Germany capable of working with this demanding material are still very few and far between.

It seems likely that French yards were the first to use AlMg4.5mn in mass-produced boats too and the unpainted aluminium finish has dominated the country’s bluewater scene since way back when. The BORÉAL, GARCIA, ALUBAT, ALLURES and META brands are recognised around the world for their creations, to which we will return later.

UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL

My views on what it is that sets French sailors apart were profoundly influenced by something that happened to me in the 1970s.

My late friend Wolfgang happened to ask if my workshop could use the help of a skilled manual worker and experienced sailor. And thus came into my life Patrice, at that time shacked up with a legal eagle from Hamburg who had recently informed him that they had tiny feet on the way. The news had inspired Patrice to start planning a new life for himself and his growing family (and it was plain enough he didn’t foresee any future for himself as a Frenchman living in Germany). Even then Polynesia was the destination on Patrice’s lips and, without prejudice to the rest of the story, I can tell you he and the family live there to this day.

Windpilot was still working in stainless steel when Patrice first appeared and I found the thought of another experienced pair of hands in the workshop very appealing. Things though quickly took a direction – a rather Gallic direction – that I had altogether failed to anticipate. The job was easily explained and involved no more than drilling a series of 5 mm holes for the then-current generation of tiller adaptor. It was straightforward manual work, I thought, and it should be fine just to leave Patrice to get on with it. Patrice saw it that way too, up to the point about getting on with it.

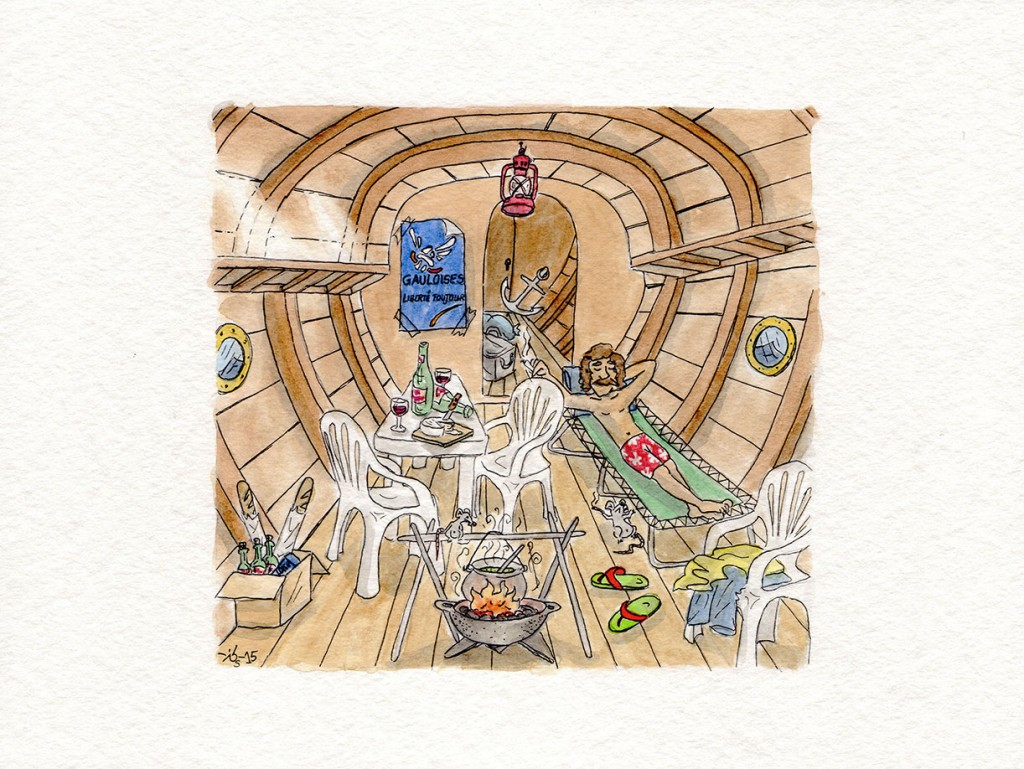

Patrice’s first day began with a few tweaks to bring the drilling workstation up to his exacting standards, which involved dragging my snow-white cocktail table over to the machine, perching a five litre flask of coffee and an ash tray on top and then pulling up a bar stool to go with it. This done, Patrice felt able to make a start. He turned up the music, drilled the odd hole, smoked a few Gauloise, drilled a few more holes, had another smoke and soon enough it was time to stop for lunch. What I had expected to be a couple of hours’ work Patrice apparently planned to spread over the rest of the week. But of course I was too polite to say anything.

Patrice, like many so many Frenchmen I’ve met, had an easy charm and an irresistible yet somehow obliging personality that made it very difficult for me to speak ill of or to him. One day he even brought me a hare to add a dash of variety to my menu. This hare, the product of a hunting expedition somewhere out to the North of Hamburg, was delivered to me in my car, skinned at least but still bloody: one moment Patrice was climbing into my red Porsche, the corpse draped around his neck like a scarf, the next he was slinging it casually behind the seats. I had actually already decided that the car would have to be sold, so I wasn’t as concerned as I might otherwise have been. The thing was, the hare’s was not the first dead body to spend time in this particular vehicle and I had had to concede that while the cadaverous stench that pervaded the car had certainly helped bring the price within my reach (it would have been an unbelievable deal for a loner with no sense of smell), it was intolerable and my best efforts had done nothing to improve matters. What use is a hot set of wheels if nobody wants to go near it? The affair with the hare only hardened my resolve: Porsche or not it had to go.

Our Franco-German alliance didn’t last long due to our vast ideological differences, the true extent of which Patrice once kindly demonstrated for me – in my capacity as owner of the means of production and oppressor of the proletariat – by pointing out that in offering him a job I had also assumed social responsibility for him and his family and that as the father of a baby it was about time I allowed him the paternity leave to which he was rightfully entitled. I found this argument difficult to reconcile with the fact that the baby had been born before he took the job, but the basic message was clear: ours would not be a long and fruitful partnership.

We subsequently reached an amicable (in the sense that no tears were shed) agreement to part ways and I threw in an oversized stainless steel Windpilot Pacific with his final pay cheque as a bonus (and delivered him and his enormous collection of baggage to the airport, where the women from Air France got a taste of the same peculiar logic that had so recently left my own head spinning). Patrice’s departure from Windpilot HQ and from Hamburg is by no means the end of the story though.

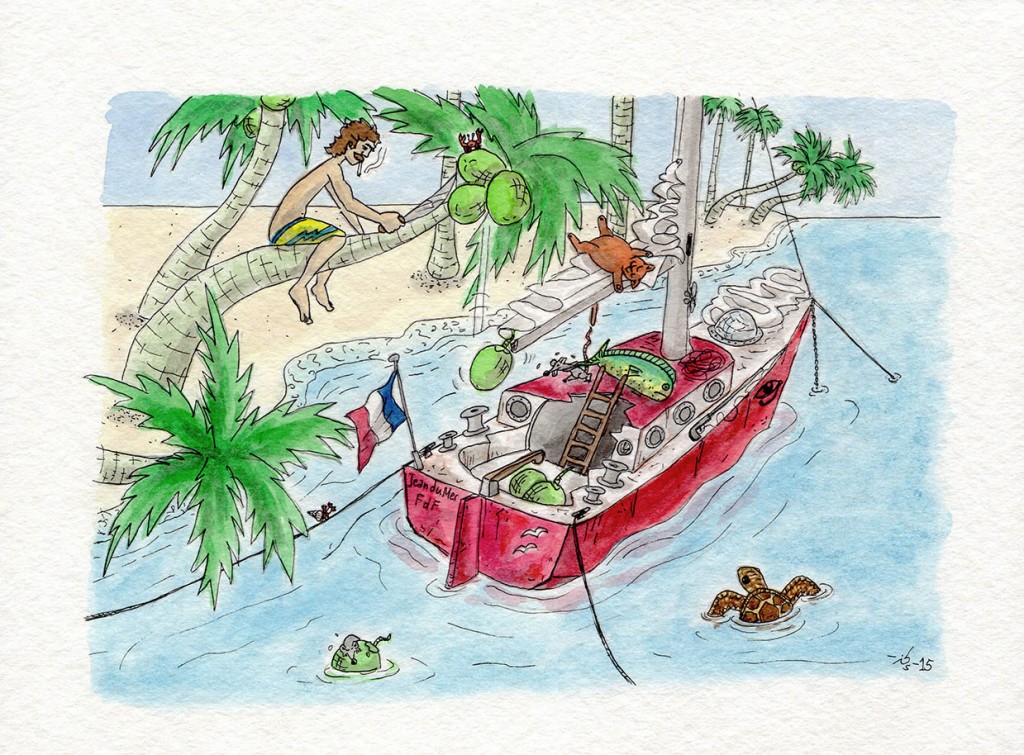

Patrice set off with a single-minded determination to continue his planned adventure westwards, at first in a wooden Dragon to which a few extra planks had been added to increase the freeboard in pursuit of enhanced seaworthiness and later in a steel-hulled creation he had managed to obtain, sans mast and interior, in a nifty swap deal after accepting that a Dragon, modified or otherwise, was no way to ship a young family over the Atlantic. A mast (with a suspicious resemblance to a telegraph pole) was procured and robustly installed and a hole was machined through the steel deck in the cockpit area through which the luxury suites below could be accessed by stepladder. Patrice’s boat was a basic, no-frills package the like of which (though it would attract no more than a sympathetic laugh in Germany before being dismissed as unsuitable for anything more ambitious than an afternoon cruise on the inland waterways) can be found around every corner in France.

Patrice, utterly ambivalent of course to what German yachtspersons might think, set off to chase the sunset with wife and heir and made it safely via the Canaries to Martinique (although they did have to anchor up in the roads well off shore on account of the fact that the boat had not been able to meet the pertinent French certification requirements, which meant that all trips ashore involved rowing the tender to a landing spot outside the officially monitored port zone).

The story ends with my friend Wolfgang (the one who first introduced me to Patrice) flying out to Martinique with his new wife for their honeymoon, a honeymoon that was to include a few lazy days’ sailing with the groom’s French friends on their yacht. Unwisely the newly-weds had neglected to inspect their floating bridal suite before departure.

As it happened Patrice did eventually collect the honeymooners, slightly dishevelled after their long flight and the transfer to the stated beach complete with roller suitcases, and row them out to the anchorage. I understand the five of them then passed the night together, in the nine metre long steel hull with no notable interior furnishings, on mattresses and camp beds. Sleep came quickly in spite of it all.

The next morning brought a memorable communal breakfast below deck in the course of which Patrice all at once swapped his camping chair for an old bucket … and took care of his morning bowel movements without leaving the camping table. The planned honeymoon cruise was terminated very shortly afterwards when the newly-wed couple adjourned to a hotel on land, apparently because the female half at least had imagined something rather different when promised yachting in Martinique. If I recall correctly the bride also gave her prince a rigorous ear-bashing into the bargain.

Patrice and family have been living in French Polynesia for decades now, he working as a carpenter and she as a teacher.

And the story of Wolfgang’s honeymoon in Martinique lives on too!

There’s more to come, promises

Peter Foerthmann