USUAL PROCEDURE?

Coming events cast their shadows before. That’s how the saying goes anyway, but it doesn’t really feel like that to me: choosing the right system, transmission lines, the functionality of emergency rudders, the key spare parts that might be needed on a long trip – all of these matters have been at the centre of my life for decades. Not much has changed in all that time. Round and round we go again. It’s enough to make one dizzy. But not me. My enjoyment of my work runs too deep and shows too plainly on my face. Even when it comes to preparations for the Golden Globe Race, which haven’t been the smoothest experience:

I would like to share a few thoughts about the fertile ground I have found here and about some of the more striking differences I have noticed working with sailors bound for the GGR start line as compared with my usual customers.

Ich möchte an dieser Stelle davon berichten, welchen Humus ich hier vorgefunden habe, in wiefern die Zusammenarbeit mit den Seglern, die beim GGR an den Start gehen, sich von meinem Alltag unterscheidet, denn es gibt einige Besonderheiten, die mir ins Auge springen, darum diese Zeilen.

BOATS

The organiser’s considered decision to limit the choice of boat to one of a small number of designs, all known for their great seaworthiness and popular in their heyday (several decades ago), has simplified things for the sailors and perhaps, to some extent, helped to keep the necessary budget down (enabling amateurs of lesser means to participate as well – at least that’s what Don McIntyre, the man behind the GGR 2018, had in mind when he drafted the rules).

The irresistible force of differing budgets has made its presence known despite this, however, with generous sponsors enabling some skippers to carry out extensive – possibly even unprecedented with boats such as these – surgery on their craft to prepare them for the tough conditions expected during the race. Sailors lacking the following breeze of a cash-rich sponsor (or several) face the significant hurdle of having to choose which, if any, of the improvements they would like to make for performance, comfort or peace of mind, can be afforded once the essential measures required to meet the organiser’s conditions of entry have been completed. It has to be remembered too that naval architects and boat-builders have different ideas today about construction, reinforcement and material and equipment dimensions for long-term use. None of the boats that will line up for the GGR was specifically conceived for anything as extreme as this event, after all, and the age of the designs means that a reasonably serious refit – at the very least – would be non-negotiable.

Quite a number of would-be participants have had to give up their ambitions over the course of the last 24 months, not least (but not only – there is probably an element of separating the wheat from the chaff about this too) because the search for sponsors has turned out to be so much more difficult than would have been hoped.

This just leaves me feeling all the more impressed by the passion and commitment of those competitors who will still make the start line despite having to fund the entire venture on the back of their own resources and resourcefulness. The hours they have had to put in and the sacrifices they have had to make almost defy belief.

Istvan Kopar, a US-based sailor with Hungarian roots, even sold his house as well as raising as much as possible through an animated crowd-funding campaign. What he has lacked in funding though he has more than made up for in determination, crossing via Bermuda to Hamble in the UK with his Tradewind 35 Puffin at the beginning of June bang on time for the start of the Sitran Challenge Race from Falmouth to Les Sables d’Olonne. The race’s two Australian contenders, Mark John Sinclair and Kevin Farebrother, sent their boats to Europe side-by-side as deck cargo before sailing the last (or should that be first?) miles to Falmouth.

I have had a wild ride in the lead-up to the GGR in my capacity as a player in the silent self-steering world. My discussions with the sailors and their teams, managers and boatyards have encompassed just about every subject imaginable that has any relevance (however slight) to my field and the number of emails back and forth runs well into the hundreds. One long-running round of correspondence in Russia with Boris Senator (Yacht Russia), Alexander Morozov (Morozov Yachts) and Michael Snegirev (360a3 Yachts SL) proved particular enjoyable for me because it centred on boats and aspects of boat design that have always been close to my heart: long-keelers with a heel-hung rudder of the type that were the obvious choice for the original GGR (they were considered the epitome of a seaworthy yacht at the time). What a contrast to the type of boat the marketing people today would have us believe makes a good bluewater choice! The Achilles’ heels of modern designs in the context of long-distance offshore sailing are clear enough for anyone who cares to look.

BOAT-BUILDING 40 YEARS AGO

I bought an unfinished Bianca 27 in 1972 and completed it myself at the yard. Mass production in GRP was already pretty well established by then and the Nicholsons, Rustlers, Lellos, Tayanas, Endurances, Tradewinds, Babas, Hans Christians, OE 32s and Vertues were already the stuff of (unaffordable) dreams for most of us. We regarded these boats as seaworthiness incarnate: wherever you might want to go, they could take you there. And, unlike their traditional wooden predecessors, these GRP boats could be made properly watertight. The mantra back then was that boats should make steady progress through the water (rather than on or over it). You may have heard the old wisecrack about the speed potential of wooden boats: a yacht made from wood will always be faster because it has all the shipworms paddling along too.

TRADITIONAL DESIGNS BACK IN FAVOUR?

Don McIntyre deserves credit for deciding to give these traditional boats a new stage. The sight of them racing around the world may well inspire sailors with big plans to think again about their own choices: after all, the laws of nature haven’t changed in 40 years. Easy travel and a comfortable life aboard are within reach, but there are certain inevitable design decisions that have to be made. Today, the balance between speed and comfort often seems to have been skewed too far towards getting there quickly, but the timeless principles of peaceful progress under sail and unobjectionable motion in a sea still apply within the cruising community. See the Koopmans range, for example…

All of the types of boat to be used in the GGR follow established design concepts that had been thoroughly proven in wood or steel even before GRP became an option. The development of GRP techniques opened up new opportunities for boatbuilders at the time by enabling them to mass-produce boats at a reasonable price to meet increased market demand.

On the GGR start line:

6 Rustler 36

3 Biscay 36

2 Tradewind 35

2 Endurance 35

1 Lello 34

1 Benello Gaia 36

1 Olle Enderlein 32

1 Eric 32

1 Nicholson 32

THE DIFFERENCES

Building a GRP hull was inexpensive, on that everyone could agree, but opinions as to the structure required to give the hull the necessary strength differed considerably. Many designs initially retained robust stringers within the hull, but it became increasingly common over time to leave them out (thus making it easier to fit the furniture). Soon it had become standard practice to rely on inner skins and internal structures to stiffen the hull other than in the keel area (a solution that had the added benefits of reducing costs and freeing up space).

The inner skin of my Bianca 27, I recall, was persuaded by heavy seas to part company with the outer skin up in the bow area, leaving some awful-looking cracks and sharp edges. I solved the problem easily enough by adding more laminate in the affected areas and filling the cavities with foam, but then as now, I would prefer it to have been built strong enough in the first place.

Nobody knew in those days just how thin you could go when building a boat. Now we do. Boats used to have a full set of ribs – and like human ribs they did more than just push the skin out. My three Hanseats (built in 1969, 1971 and 1977 respectively) had solid 35 mm laminate in the keel area plus very substantial stringers from stem to stern. All was quiet below deck even in heavy weather: no creaking and straining to be heard here.

Other than the sole new build for the GGR, a wood epoxy composite Eric 32 (Suhaili replica), all of the boats entered were built before 1988 and I am especially pleased to see that no fewer than six participants have chosen the Rustler 36, my life-long favourite, to take them around the orange. The Rustler 36 (or indeed the Giles 38) is the logical tip of the pyramid for a sailor like me who had a Folkboat in the early days, subsequently moved up to a Bianca 27 and has an enduring preference for this type of boat.

One feature common to all of these boats is a square stern in which the trailing edge of the keel and the transom occupy the same plane and form a contiguous structure to which the rudder is robustly connected from top to bottom (and in a position that hides nothing from view). Simplicity itself, in other words. What few sailors will have realised, I suspect, is that many boats built to this pattern have the main rudder mounted on four bearings all along its length, a configuration that makes all the difference in the world compared to today’s mainstream solution of using just two quite closely spaced bearings.

Not surprisingly, Windpilot has equipped a great many Rustler 36s.

The Rustler 36 is an evergreen design that has been built to essentially the same plan for decades and has a strong international fan base (for evidence of which look no further than the prices commanded by used examples). The GGR seems likely to bring priceless publicity and media attention for the RUSTLER YARD in Falmouth, UK. The company cannot have imagined such a windfall prior to the announcement of the GGR 2018, but I would suggest they certainly deserve it.

Several of the boats entered for the GGR turned out on close inspection to require extensive work. Russian skipper Igor Zaretskiy’s Endurance 35 Esmeralda, for example, was found to need its entire wheel steering system and main rudder replaced. Australian Mark John Sinclair also had to build a new rudder for his Lello 34 Coconut, a process he describes in some detail here

Francesco Cappelletti’s story of the race-before-the-race to prepare his Endurance 35 can be found here.

Antoine Cousot´s Métier Intérim one of three Biscay 36s entered, has been back to Falmouth and the yard that built it for an extensive refit that included installing additional bulkheads and reinforcement. It is surely no coincidence that half of the boats heading to the GGR start line were built in Falmouth, a part of the British coast where the importance of robustness and good seakeeping characteristics cannot be ignored.

The radical steps taken to strengthen and, in some cases, rebuild the GGR’s fleet of traditional GRP boats in preparation for the challenges to come are (presumably) without precedent and it would undoubtedly be very interesting to compile and analyse the details of the condition of these mass-produced boats and the work required to bring them (back) up to scratch for the race. The mere fact that the great majority of the boats starting the GGR will already have 30 or 40 years under keel is sure to give a good few onlooking sailors pause to reflect: according to the thinking that underpins the current market, anything this old should be given the last rights as unsaleable or no longer structurally sound.

Two of the GGR projects have particularly caught my eye on the strength of their unusual and idealistic background.

SV THURIYA – ABILASH TOMY – INDIA

I have been following two parallel projects to build a new Eric 32, the legendary Atkins design on which Suhaili was based, for some time. Dutchman Johan Vels was my contact for the project under construction in India, while my South African friend Colin Davis (a man who knows all about circumnavigating with a Windpilot) opened communications with Hamburg on behalf of his friend Mike Smith in Australia.

Both of these new build projects, undertaken without the support of international sponsors, were only possible thanks to the extraordinary idealism and diligence of the people involved (Mike Smith, it should be noted, withdrew from the provisional GGR start list very early on to concentrate on his project free from external time and financial pressure). I should also mention that Abilash Tomy’s decision to build his boat in India was not just a matter of convenience: Robin Knox-Johnston’s Suhaili was herself constructed in Bombay.

Johan and I discussed any number of details as the build progressed and at the end of May 2018 we joined Abilash Tomy and his manager, friend and fellow circumnavigator Dilip Donde aboard Thuriya in Medemblik to unite it with its sails. The boat travelled as deck cargo from India to Holland, where the finishing touches were applied with Johan’s help and supervision. My respect – my admiration – for this project knows no bounds: it is simply astonishing what has been achieved.

A CRAZY IDEA – IN A CRAZY SETTING – WITH CRAZY FRIENDS

Johan Vels beschreibt sein Input zu diesem Projekt mit eigenen Worten:

I am hooked to the Indian scenery for more than 10 years. Started with the project of Mhadei, the first Indian boat Dilip ( Donde ) made his circumnavigation. I was “forced” by the navy as supervisor because the design of Mhadei was V.d. Stadt (they recommended me for that)

Ratnakar the Yard owner and Dilip became friends, the Yard hired me for other projects nearly every year than. The Yard grow from a tiny shed on the river Mandovi to a big yard with more than 100 employees.The GGR project started with an Indian private sponsor of Abhilash. After the sponsor quitted, I worked without sending Bills. ( I transformed the whole concept of Suhaili to wood/epoxy etc.). So finally, 90 % of my input was unpaid because I was involved by a crazy Idea in a crazy setting with crazy friends …

I’ll allow Johan Vels to describe his input into the project in his own words:

I am hooked to the Indian scenery for more than 10 years. Started with the project of Mhadei, the first Indian boat Dilip (Donde) made his circumnavigation. I was “forced” by the navy as supervisor because the design of Mhadei was V.d. Stadt (they recommended me for that)

Ratnakar the Yard owner and Dilip became friends, the Yard hired me for other projects nearly every year than. The Yard grow from a tiny shed on the river Mandovi to a big yard with more than 100 employees.

The GGR project started with an Indian private sponsor of Abhilash. After the sponsor quitted, I worked without sending Bills. (I transformed the whole concept of Suhaili to wood/epoxy etc.). So finally, 90% of my input was unpaid because I was involved by a crazy idea in a crazy setting with crazy friends …

Abilash’s story, the achievements that enabled him to consider the GGR in the first place, his willingness to give up so much – even his secure commission with the Indian Navy (which subsequently decided to grant him a sabbatical instead) – for the project and his tireless work to see it home give some idea of the courage and strength of mind required to put Thuriya on the start line. He managed to fit his wedding in there too, somehow… I find it particularly interesting that the whole project came to fruition without big corporate sponsors: this was a series of joint efforts involving a large number of committed individuals and marine industry businesses, each contributing what they could (goods and services alike) to help Thuriya make the race.

SV ASTERIA – TAPIO LEHTINEN FIN

Tapio and I have exchanged something like 150 e-mails (and counting) concerning his GGR campaign, which perhaps gives some inkling of the mountain he and his team have had to climb to make Les Sables. The self-steering issue was settled quite quickly:

As I drive with a German VW and my daughter went to the Deutsche Schule (nein, I spreche night Deutsch), I would like to consider Windpilot.

I would like to hear your ideas of which one of your vanes would suit best my long keeled S&S RORC racing boat from 1965 (the long keel is relatively short with long overhangs). I already have my idea of how the boat should be steered by a wind vane or which model would be best for the race, but I would first like to hear your suggestion.

I am a keen racing sailor, I have been racing my classic Six Meter for over three decades, my children Silja and Lauri sailed in the Quingdao (Silja) and London (both) Olympics and I am trying to prepare for the GGR in such a way that I would have realistic possibilities to be among the top boats.

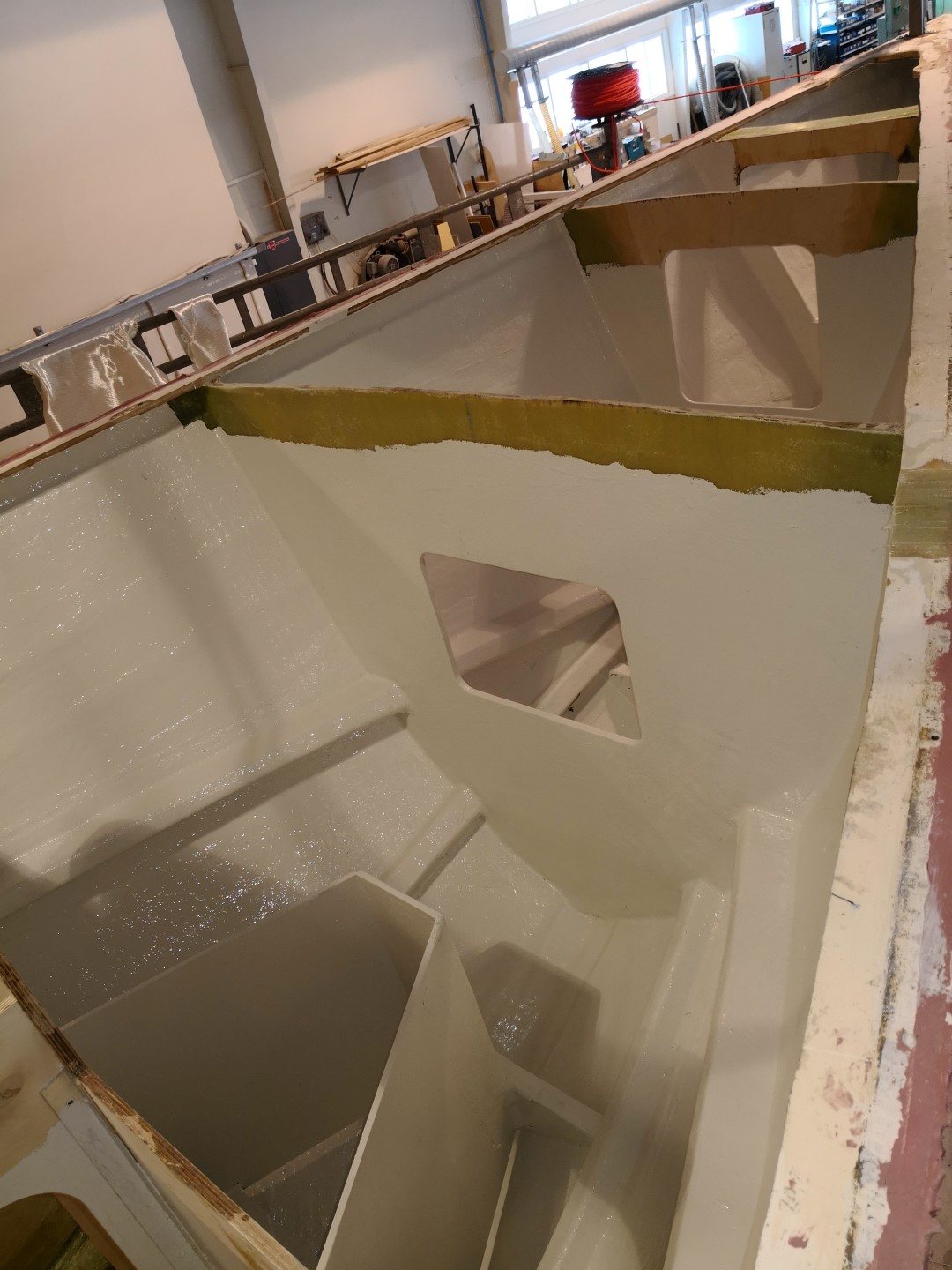

Tapio bought his Asteria in Italy, sailed it back to Finland in the summer of 2017 and lifted it at Jan Lindell´s yard for a refit the likes of which few boats can ever have undergone: the boat was gutted down to the bare hull, had new reinforcing structures laminated in and was then fitted out again from scratch. All of this was completed in the space of just a few months far up in the North of Finland, from where the boat was shipped to Zeebrugge to be re-rigged. The passage to Falmouth became Tapio’s sea trial, his chance to test and familiarise himself with the many onboard systems that he had not previously been able to use in earnest. His Windpilot was one such system: Tapio had never sailed with silent self-steering before (unlike fellow competitor Igor Zaretskiy of Russia, for example, who has already won the OSTAR with a Windpilot).

One component that obviously caused Tapio problems on the way to Falmouth was his engine: he arrived under tow behind Norwegian entrant Are Wiig’s Olleanna. Despite our intensive communications over the last few months, Tapio was the only one of the Windpilot sailors in the GGR that I had not met face-to-face prior to the pre-race gathering in Les Sables.

THE SPONSORSHIP TANGO

It appears Dutch sailor Mark Slats might not have been able to complete his preparations for the GGR had he not managed to find a sponsor for his project at short notice. Mark has enjoyed the comradeship, support and advice of his friend Dick Koopmans from the very beginning.

A whole series of sponsors seem to have been won over in recent weeks and put significant resources into sailors and the event organisation (the big clue often being a change of boat name or the sudden appearance of a new paint-job/wrap).

Mark Slats – Ophen Maverick – Cloud-based core banking engine

Philippe Peche – PRB – building coatings

Jean-Luc Van Den Heede – Matmut – insurance

Susie Goodall – DHL Starlight – logistics

Antoine Cousot – Metier Interim – employment agency

Gregor McGuckin – Hanley Energy Endurance – global data solutions

Igor Zaretskiy – Esmeralda – Double V, Russian packaging group

British sailor Susie Goodall probably has the strongest starting position: a photogenic young yachtswoman with the added attraction of being the sole female competitor in a starting line-up dominated by men, she appears to have been giving her sponsor DHL Express an excellent return on its investment for months already.

Most competitors have found it much more difficult to drum up any enthusiasm among potential sponsors though, with big corporate names that might have been expected to take an interest conspicuous by their absence. Event organiser Don McIntyre ran into much the same headwinds himself, of course, but fortunately persevered with his quest to make a reality of the GGR 2018 (presumably digging deep into his own resources in the process). His commitment too deserves the utmost respect.

SPONSOR DISTANCE

Sponsors want media coverage publicising their brand as widely as possible. A boat with a high-profile skipper can be a good bet in this respect because the length of the event provides plenty of opportunity for boat and skipper to make regular headlines. The key for skippers is to hold out to the finish if at all possible so that their backers receive maximum exposure. I suspect all of the GGR sailors to have attracted sponsorship from big companies will have put all the money made available to them into the boat to optimise their preparations.

Sponsors providing assistance in kind follow a slightly different model. They will usually have been in close contact with the sailors to whom they have extended discounts or free goods/services in anticipation of a boost for their brand through general media coverage of the sailors and their boats. These types of sponsorship arrangement obviously presuppose a high level of mutual trust and respect between the people involved.

RIDING THE RAZOR´S EDGE

I made the decision to support several sailors even though using a windvane self-steering system in a race might seem likely to force competitors to temper their competitive drive somewhat. Windvane self-steering systems reward good seamanship: as always under sail, the best results come with good trim and a balanced helm. Sailing with excessive weather helm and frequent course corrections is like driving with the handbrake on: every rudder movement creates speed-killing drag. Windvane self-steering systems are by their very nature unable to perform big course changes quickly, as their maximum rudder angle is limited by design (not least in order to prevent oversteering). This is why they are limited almost exclusively to cruising yachts.

When I talk about my involvement as riding the razor’s edge, it is this potential conflict that I have in mind: I can only hope that the sailors manage to harness their ambition and their understanding of good trim and a balanced sail plan to the same carriage. Windvane self-steering is no magic bullet, but good systems will encourage their owner to trim with awareness and diligence – and reward them with the opportunity to pay proper attention to everything else that goes into a (relatively) fast and safe circumnavigation (chief among them bunk time).

I have discussed the intricacies of windvane self-steering at length with our Windpilot sailors (two of whom, being from a racing background, had never used one before) in the lead-up to the race. I have kept an eye on system installation and the arrangement of transmission lines and will no doubt have gone through the “one last check” routine several more times before I wave them off from Les Sables.

After that, we can but watch the adventure unfold. Once they head out to the start line, everything rests in the hands of the skippers. I hope that my advice will have been received and understood and that it will be put into practice: that will be reward enough for my efforts,

assures

Peter Foerthmann