SAIL IN BALANCE, LIVE IN BALANCE

Self-Steering under Sail is both the title of a book (a book crammed full of information about how to make yourself obsolete in your own cockpit) and the subject that has dominated my working life, bringing me pleasure and friendship and showing how a person can make a living – in balance – on the back of a few simple rules.

The very thought of sailing makes me sleepy: my boat comfortably balanced with its Windpilot in control, the skipper dreaming contented dreams in his bunk – over and over again with never the slightest hitch (but sometimes with a Paolo Conte soundtrack). How wonderfully sublime to lie back and feel a well-balanced boat (with windvane self-steering system) sailing itself. But all too soon such thoughts are overtaken by weariness, the mind surreptitiously lulled into sleep because of a mysterious irresistible link between the sounds of the sea and the weight of the seafarer’s eyelids – a trap one can only escape with an ingenious and effective invention, an uncomplaining slave for the helm that leaves the skipper to sleep in peace while keeping the boat in sync with the wind and waves and ticking off the miles at pace.

My continuous development of transom ornaments has been a purely self-serving exercise with the added bonus of paying for my existence. And just as the self-steering business has paid for me, so I have paid for my involvement in the self-steering business. The windvane sector is pretty small even at the global level, so it is very easy to attract attention: expressing an opinion is really all it takes. Repeatedly and vehemently. The endless loop of my life… Here is my report.

Windvane self-steering systems are master teachers: there’s no such thing as “it doesn’t work!” It all ultimately comes down to sailing in balance: if big rudder movements are what it takes to stay on course, there’s likely too much canvas aloft and the race is soon lost. Sailing with the handbrake on makes no sense with a human – rapidly tiring and better employed on more cerebral pursuits – at the controls and no more sense with a mechanical substitute in his or her place.

Message received and understood (a thousand times over) right? Perhaps it depends on what we mean by “understood”. We often see a yawning gap between theory and practice and this gap has a name: ambition. Ambition begins to gnaw away at the soul as soon as the sailor becomes competitive, with himself/herself or others, and loses sight of the importance of balance. Can it be right to abandon common sense (or prudent seamanship, as it might be called in our context) just because the enemy is on your tail? Participants in the GGR faced a dilemma very much like this for months on end.

WINDVANE SELF-STEERING SYSTEMS ROAD-TESTED IN THE GGR

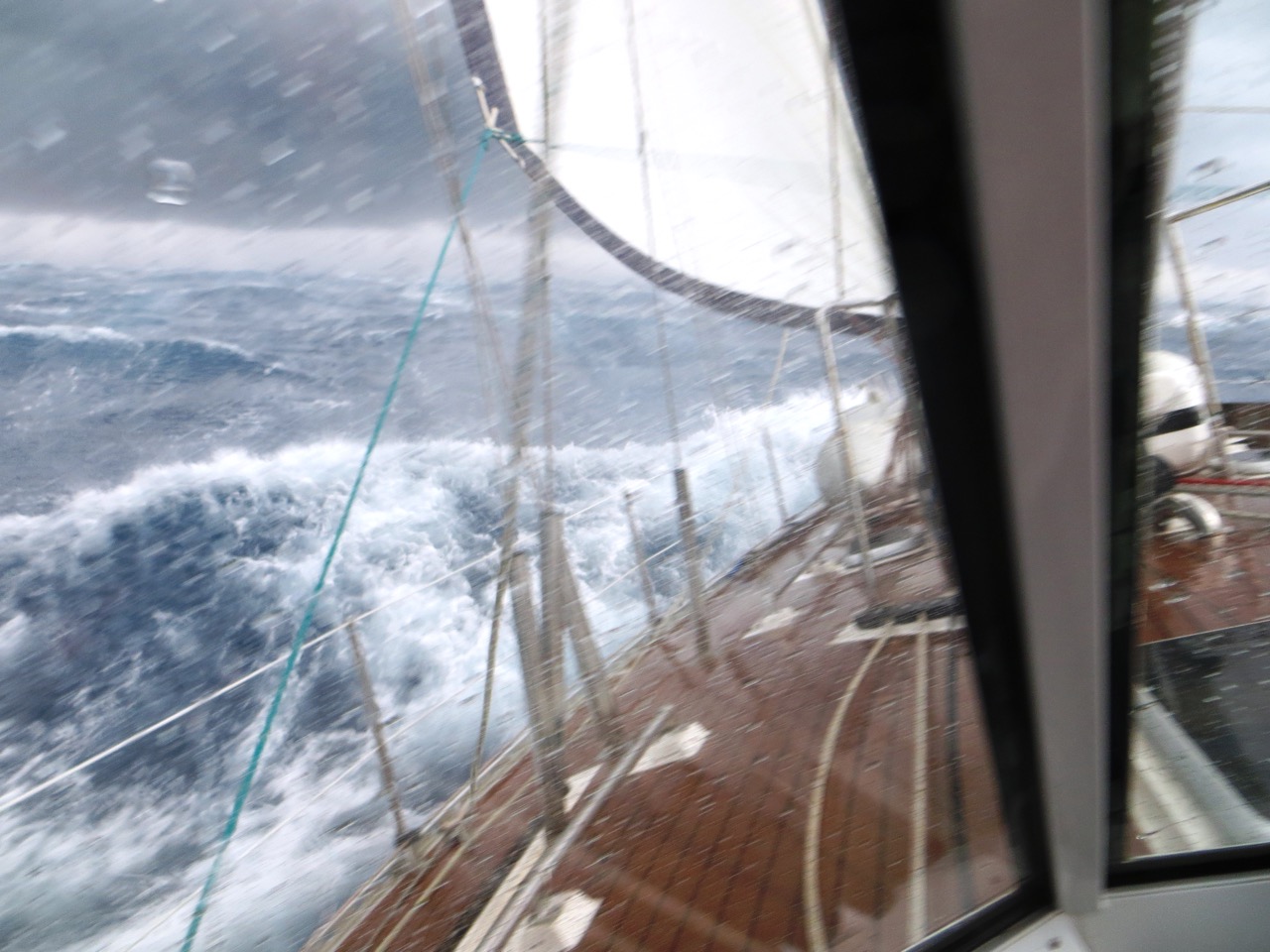

Hardly! Windvane self-steering systems are not a tool for racing, especially not in high latitudes, so their use in the GGR was always going to push them to their limits and leave their skippers riding the razor’s edge. The fate of every GGR participant was inextricably entwined throughout the race with that of his or her windvane self-steering system. Problems could (and did) mean game over because, with electrical autopilots being banned, the only option in the absence of a reliable vanegear was to start steering by hand – immediately and potentially for the rest of the race. There can be little worse for a non-stop solo sailor, especially when the sleep deprivation starts to kick in as well.

Success in the recent race came to those who managed to combine sound seamanship with extensive experience and robust and reliable self-steering. The human side has probably been covered sufficiently already: nothing good happens unless skipper and machine are working in harmony. But what if harmony and balance are lost? Does the blame accrue to the flesh and blood or the nuts and bolts? One, of course, can speak up for itself but the other has no voice to defend its virtue, all of which leaves windvane self-steering system manufacturers dangerously vulnerable. Being the purveyor of vital equipment tees one up perfectly for the role of fall guy, a role in which I was to star in the GGR.

When designing things like aircraft and bridges, engineers and architects include very substantial safety margins to ensure their creations are reliable and durable: no sacrificial links or designed-in points of failure to see here! Different rules apply when it comes to sailing boats, however, with past experience of what works and what does not always spurring designers and their customers on. Stresses are calculated, loads modelled and strengths tested – and the results are no doubt a wonderful and precise resource. The challenges of the real world have never bowed down to theory, however, so failure inevitably comes anyway, probably when reality moves just beyond the maximum predicted load. Some sailors love to push the design envelope and ride the razor’s edge!

Owners at the forefront of fast sailing yacht design today have some remarkable beasts in their stable, a striking testament to what can be achieved with ambition, committed (deep-pocketed) sponsors and cutting-edge boat-building techniques. The French continue to lead the way in this respect. But, amazing as the latest racing craft undoubtedly are, this is not my world at all.

Windvane self-steering systems (WSS) are a different story altogether, with many still based very much on lessons learned in 1968. This is due not so much to a shortage of knowledge or new ideas as to a lack of willingness to innovate and the not-unrelated factor of a market with low expectations. Anyone with a passing interest in the subject can see where improvements might be made: the wonderfully incontrovertible principles of physics ensure every frailty betrays itself sooner or later.

Conceived for extended travel at sea, WSS have ornamented the transom of cruising yachts in their thousands. The physical laws governing the relationship between boat, trim and self-steering are set in stone, as are the limits to what WSS can achieve: with no eyes to spot breaking waves or other hazards, windvane self-steering systems stick resolutely to the task of maintaining the defined wind angle – even if this takes them straight through the wave. Sailors have every right to expect good steering from the WSS but cannot expect it to make good decisions as well. It is down to them, rather than their equipment, to exercise sound judgement and be prepared to steer by hand when conditions become too challenging.

REDUNDANCY

Half a century of empirical evidence in relation to WSS tells us that sailors usually add a windvane as backup for their existing autopilot only to discover, to their astonishment, that it is the autopilot (AP) that ends up playing second fiddle. Sailors who have both systems (WSS and AP) on board and crew as well actually have multiple levels of redundancy: if things really go pear-shaped, someone can be ordered from their bunk. This being the case (and it usually is), the show can generally go on even if the WSS picks up an injury.

The situation for the GGR boats was quite different, because autopilots (and crew!) are banned in the rules. Awe-inspiring as the extensive rulebook for the GGR may be, I think this strict ban is probably a mistake. The rules were modified in a number of ways to allow modern technology onto the boats and will probably be modified further in future. At least I certainly hope they will be.

Comparing the GGR with La Longue Route (LLR), we can see that Susanne Huber-Curphy’s autopilot-equipped Nehaj, for example, emerged with no on-board emergencies despite encountering five severe storms. Significantly, Susanne deployed a Jordan Series Drogue during the worst of the weather. She was able to commit to this time-consuming safety measure in part because she had the option of taking her Aries out of action and letting the autopilot do the work instead for a while (trying to get a series drogue and all of its spaghetti into the water with the servo-pendulum rudder still in position doesn’t bear thinking about). Other LLR boats did the same thing, which probably goes a long way to explaining why that race had no near-disasters at the same time as the GGR was producing one after another.

THE DANGERS IN DETAIL

WAVE SYSTEMS

The challenges of racing hard in the high latitudes have been clearly set out by Robin Knox-Johnston (RKJ). The prevailing conditions down below the great capes allow the development of wave formations that, with no land to interfere, are free to run and grow until a sudden windshift during the passage of a storm interrupts their rhythm. Secondary waves at a different angle now appear, interfering with the regular wave pattern and creating chaotic peaks and troughs that pose a grave threat to sailors ensnared in the middle. Smaller traditional long-keelers are particularly vulnerable because, unlike faster designs with the ability to surf, they lack the speed necessary to escape oncoming weather systems.

KNOCK DOWNS, ROLLOVERS AND PITCHPOLES

These are the hazards awaiting sailing boats in the high latitudes. Of particular interest to me (naturally) are DESIGNATED POINTS OF FAILURE/OVERLOAD PROTECTION FITTINGS on WSS, because once they have failed/tripped, the WSS remains unavailable to steer until it has been repaired (until the failed component has been replaced) or reset. This trap may well have contributed to the downfall of Are Wiig and Susie Goodall, as both found themselves having to steer by hand in emergency situations.

DESIGNATED POINTS OF FAILURE

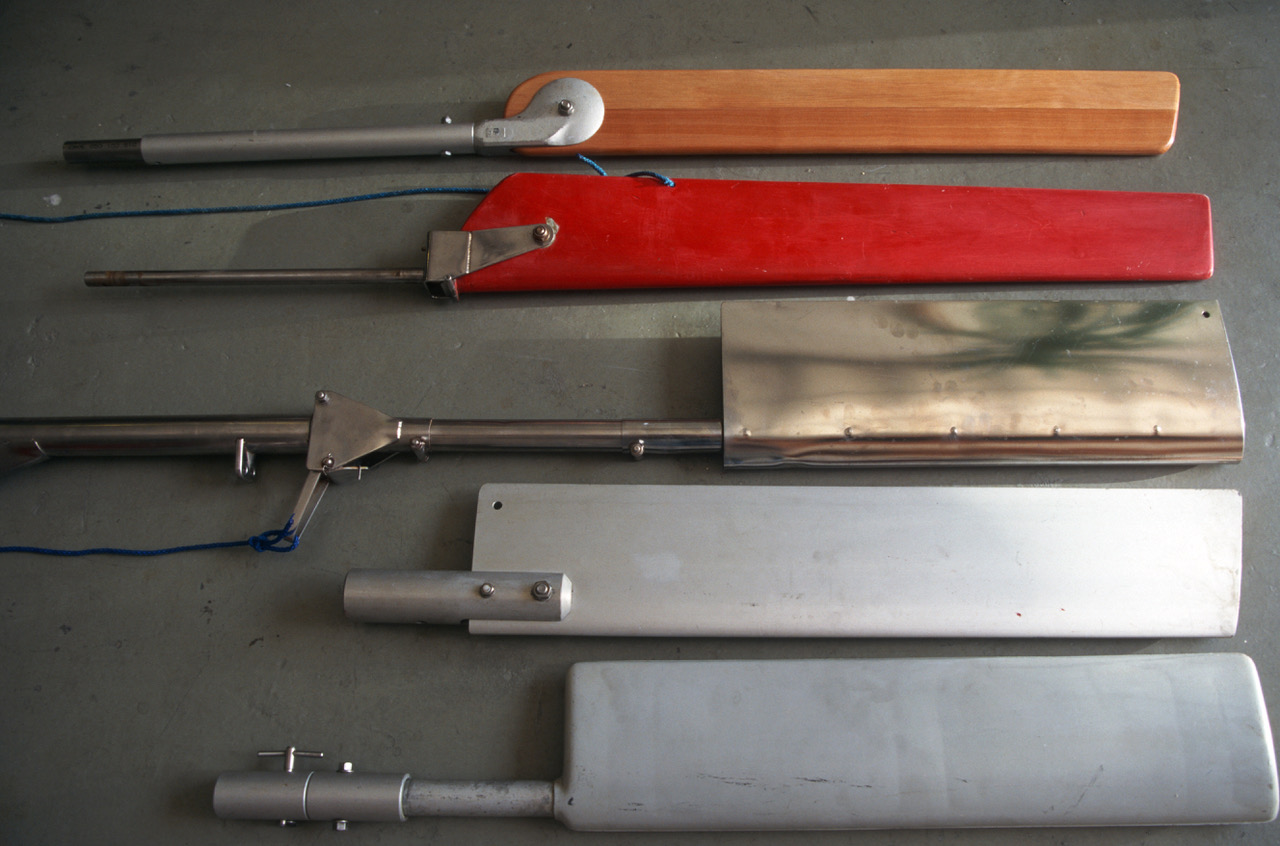

A designated point of failure is a weakness intentionally designed into the system so that when overloaded (in this case during extreme weather), the system will fail in a predictable way that avoids more serious damage to the system or its mounting on the transom.

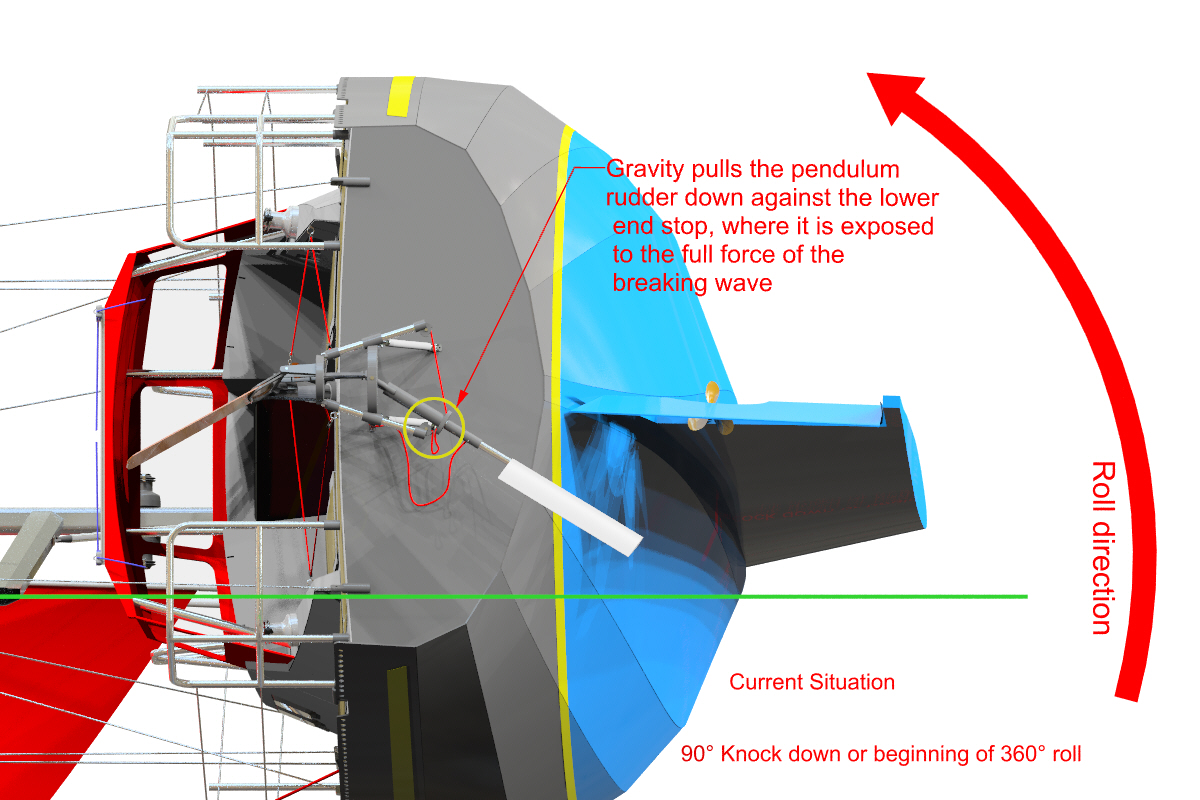

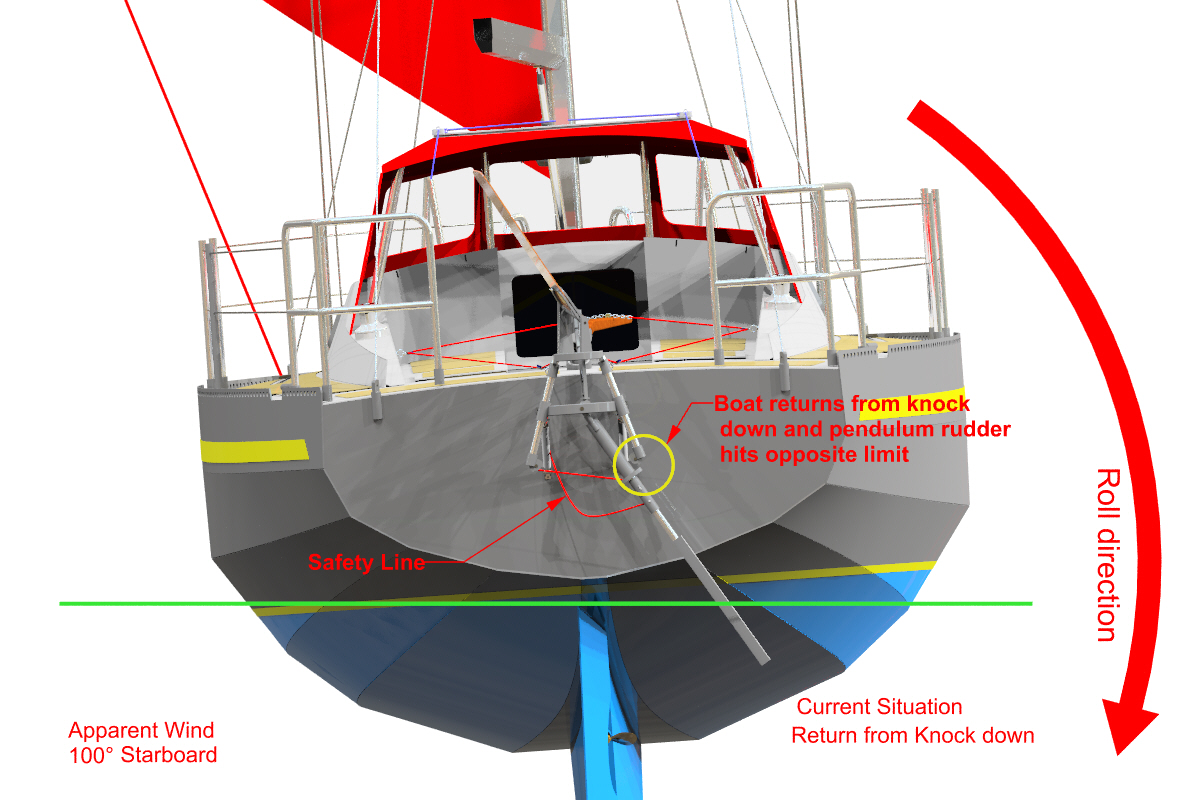

Resilient elements (friction systems, latching, shear pins or spring-loaded joints) built into the system can take the sting out of impacts to the rudder blade or shaft (as might be caused by flotsam, for example), but the – lateral – forces involved in a knock down, rollover or pitchpole are far greater because in striving to maintain their dynamic position at the stern, rudder and shaft are likely to come up very hard against the frame that limits their lateral travel.

Thousands of Aries systems over the years have enjoyed excellent protection in this and other scenarios thanks to their designated point of failure – a tubular section that has had its wall thickness ground down from 6 mm to 3 mm. Provided the rudder was tethered to the boat with a safety line and there is a replacement tube available, all the crew has to do to carry on sailing is fit the new designated point of failure.

ACHILLES´HEEL

It is a common – indeed inevitable – feature of all brands and models of WSS that the tripping of the overload protection temporarily puts the system out of action. If the rudder has simply been bumped out of alignment by something in the water, the system can usually be reset easily with no need of tools (realign rudder blade, re-engage and calibrate). Bringing the system back online after an actual breakage due to overloading, on the other hand, will always take a bit of time because tools and spare parts are required and accessing the parts of the system affected while remaining on the boat can be quite a challenge. This, then, is the Achilles’ heel of any WSS for a solo sailor with no backup system.

HYDROVANE

Hydrovane incorporates overload protection in the form of three “locking pins” (shear pins). These, the manufacturer advises, should be rotated or replaced regularly to prevent failure due to wear/vibration:

ROTATE LOCKING PINS – The Locking pins are interchangeable. The pins – especially Shaft Locking Pin #61 – will suffer from metal fatigue over time. Best to periodically change it with spares or rotate it with the other locking pins.

Jean-Luc van den Heede replaced the shear pin with a solid bolt. The bolt did break during the GGR, but Jean-Luc is not so easily fooled: he had a safety line tied snugly to the WSS rudder to ensure it would stay with the boat in such circumstances. His preparations also included reducing the length of the system’s auxiliary rudder, which has the effect of lightening the load on the shear pins.

Loïc Lepage’s WSS apparently also suffered a broken shear pin. The WSS was not responsible for the damage (leading to abandonment in the latter two cases) suffered by Jean-Luc van den Heede, Loïc Lepage and Gregor McGuckin.

Uku Randmaa recorded three knock downs. His WSS remained intact (he had a Monitor installed for redundancy too).

Rotating or replacing the shear pin located down on the shaft out of arm’s reach from the deck is not at all easy and this was one of the reasons Istvan Kopar decided against the Hydrovane. Re-installing the rudder/installing a replacement rudder after a breakage at sea poses even more of a challenge given the difficulty of working close to the waterline while hanging over the stern. Anticipating just such a situation, Jean-Luc van den Heede actually took an inflatable dinghy along to help him reattach his WSS rudder (the rudder he managed not to lose, as already mentioned, by tethering it to the boat with a snug safety line).

ARIES

Inventor NICK FRANKLIN supplied his Aries for decades with a designated point of failure called the “break off tube”, multiple replacements for which were part of the standard onboard toolkit for owners. The safety line attached to the rudder to keep it in contact with the boat when the tube broke became part of the classic Aries look.

The “hinge” developed by Nicks’s successor Peter Mathiesen deals well with flotsam but does not protect against more serious lateral overloading (perhaps owing to the Danish proprietor’s interesting theory that the materials used are strong enough to survive bad weather and its consequences unharmed).

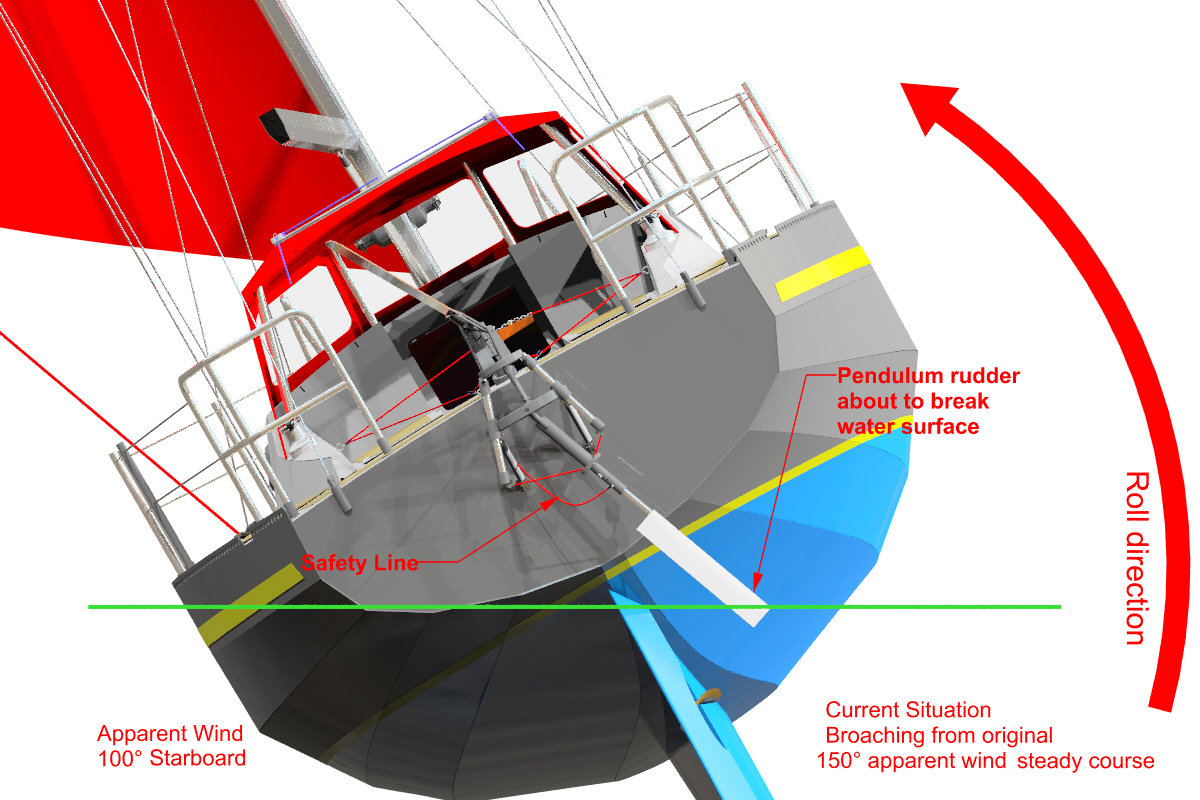

Mark Slats´ WSS appears to have been exposed to a quite severe impact judging by the damage done to what would ordinarily be considered a very robust mounting arrangement. Presumably the pendulum rudder hit the lateral end stop with great force during a knock down – it is hard to imagine any other scenario that could produce this result.

Marc Sinclair managed to keep his mast pointing more or less skyward throughout and his WSS remained intact.

I believe the decision to replace the old Aries break off tube with the hinge was made mainly to improve everyday ease of use, as the original model did not allow the rudder to be swung up out of the water. But what about lateral overload protection? Current manufacturer Lean Nelis apparently recommends removing the WSS rudder in heavy weather:

The new lift-up leg is great to take off the pendulum rudder completely! – Either while in port – Or to keep her from damage in case you are becalmed in heavy swells – Or in case you have to survive a storm with your ‘Jordan Series Drogue’

The MONITOR

The Monitor has been supplied for years with a hinge and a safety tube for overload protection (and again, most owners probably keep several spare safety tubes on hand).

Are Wiig: experienced multiple broken safety tubes (he was down to his last replacement by the time he abandoned) and it seems quite likely that this contributed to his knock down and dismasting given the problems that come with having to steer by hand whenever the WSS is out of action.

Multiple broken safety tubes were part and parcel of the race for Susie Goodall too. She also had the two gear segments that link the vane to the rudder shaft jump out of alignment. Normally the teeth of the two gears mesh together so that the vane and the rudder are both on centreline at the same time, but in Susie’s case something – presumably the rudder shaft hitting one of its lateral end stops very hard – caused the teeth to jump over each other. Obviously the WSS cannot work properly if windvane and rudder are not aligned. Susie repaired the system in calm water off Hobart but it seems the same thing may have happened again later on, with a fateful interaction between the JSD and WSS suspected of being a key link in the chain of events that ended with the pitchpole and subsequent loss of the boat.

The mechanism designed so that the pendulum rudder can lift up when not in use acts as a spring-loaded joint that, once tripped (either by flotsam or intentionally using the lifting line), allows the rudder to pivot up aftward.

Lateral overload protection is apparently provided by using thin-walled stainless steel tube (although note that the organizer announced in April that the manufacturer had apparently increased the wall thickness of the rudder shaft tube).

WINDPILOT

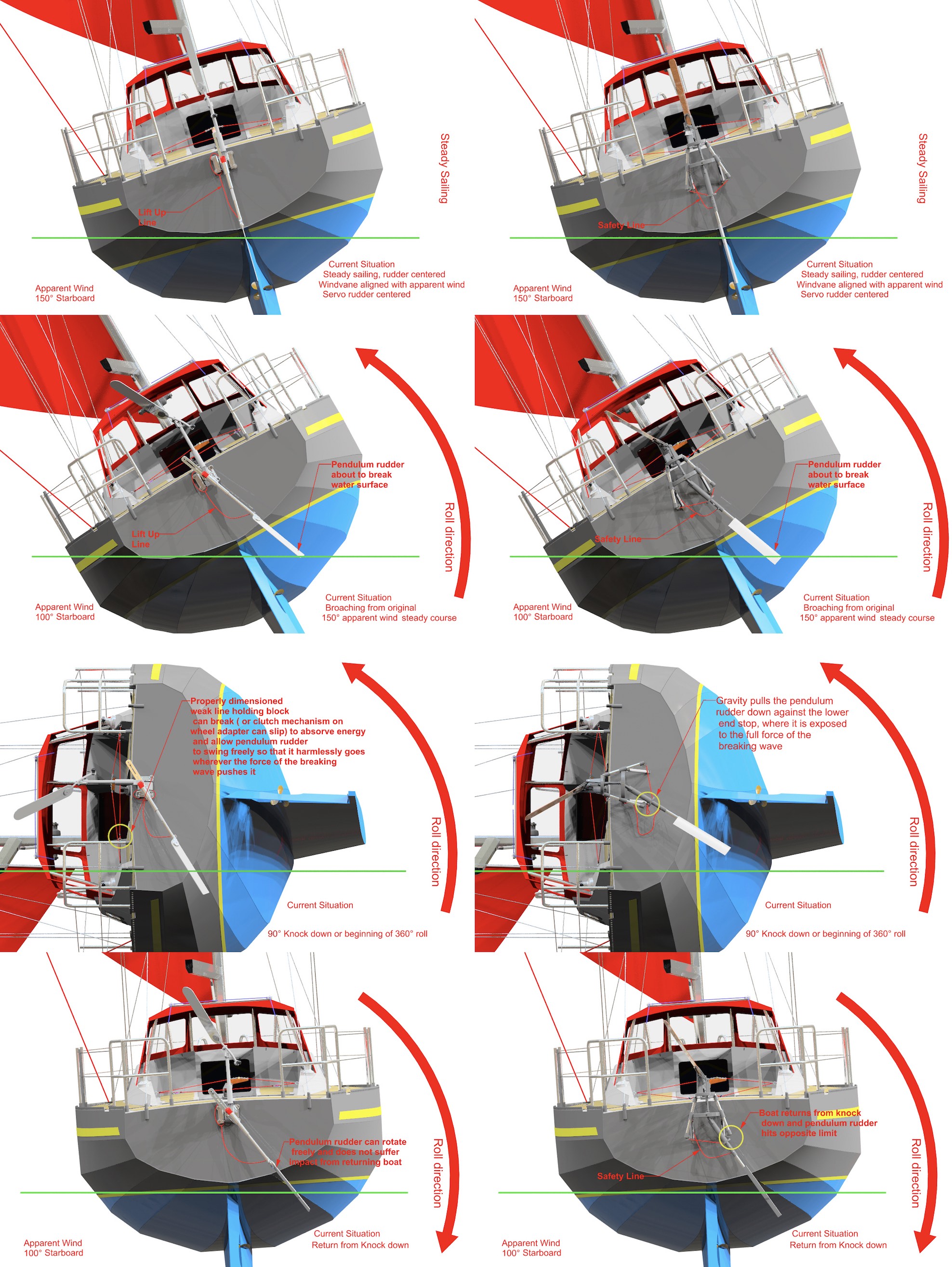

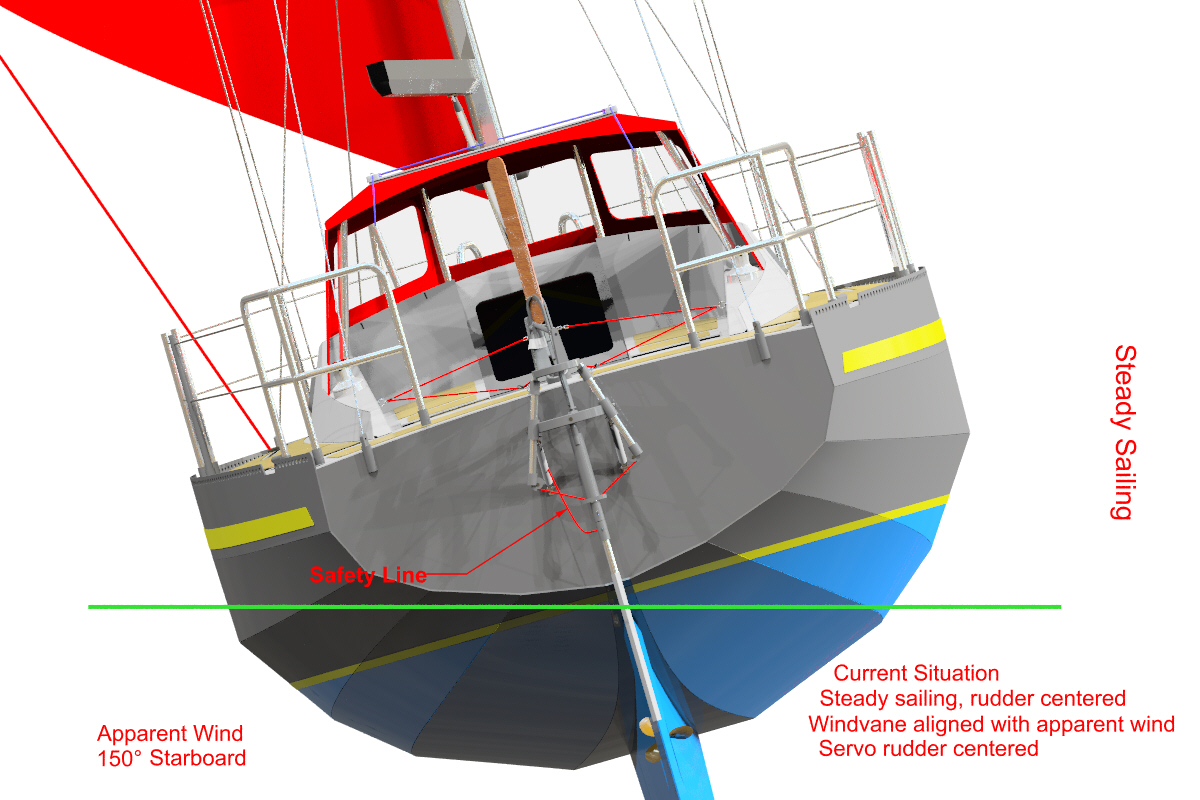

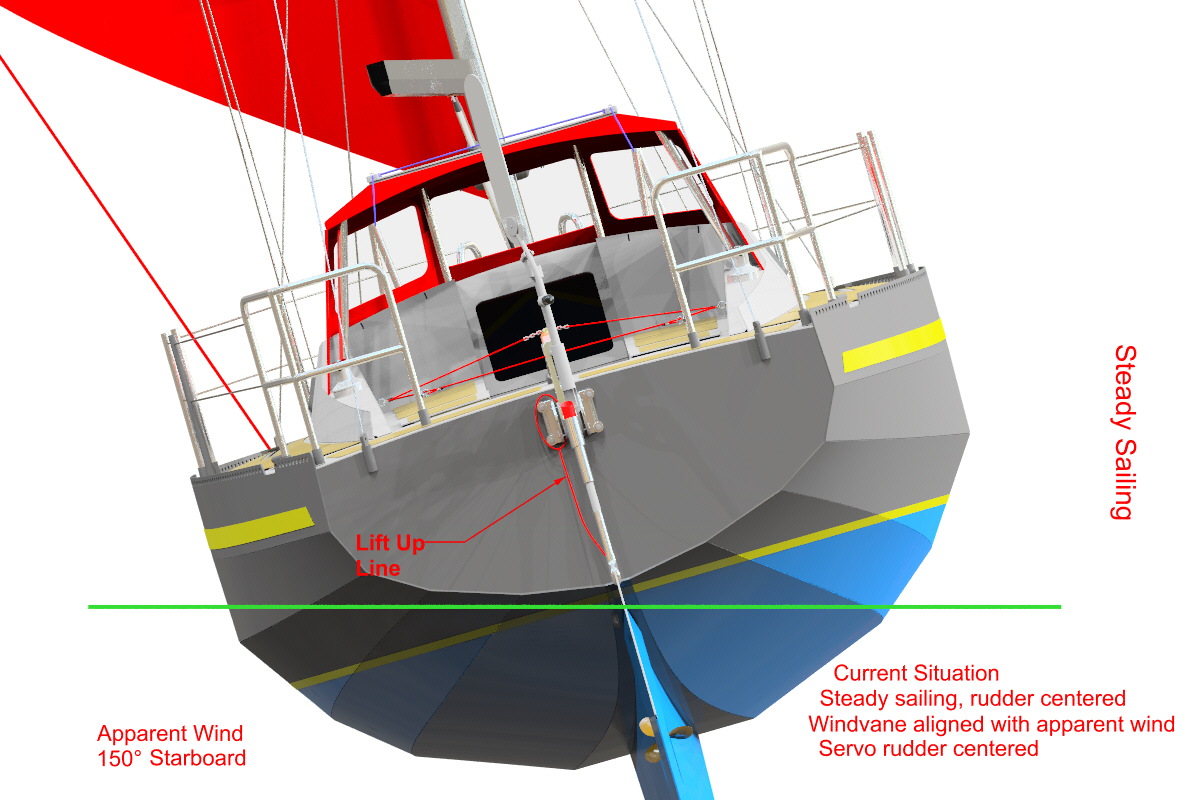

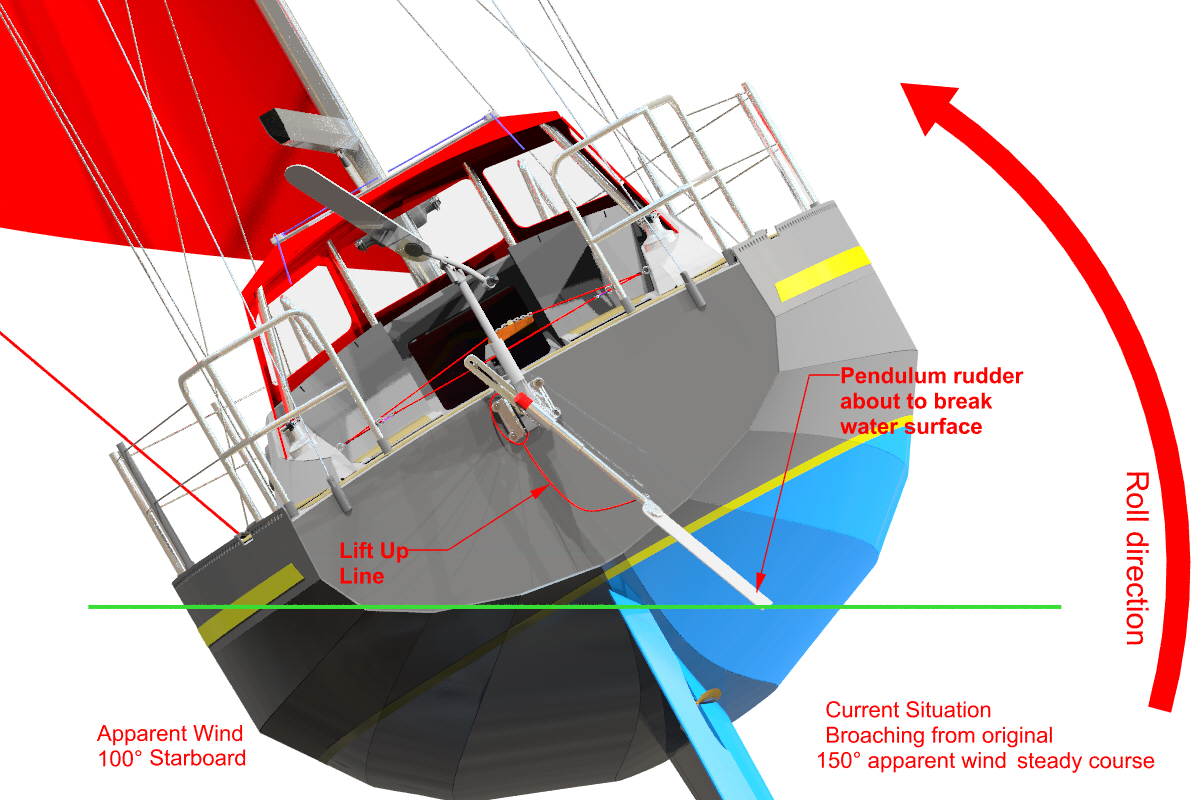

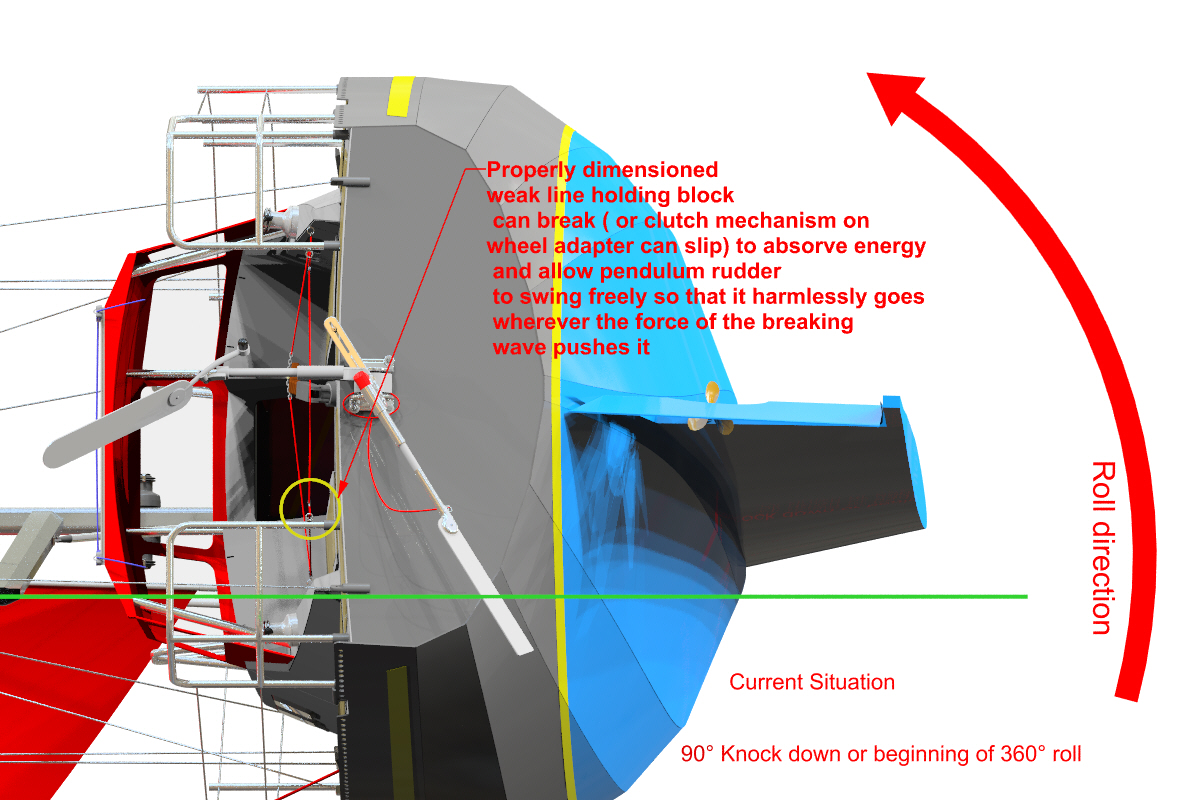

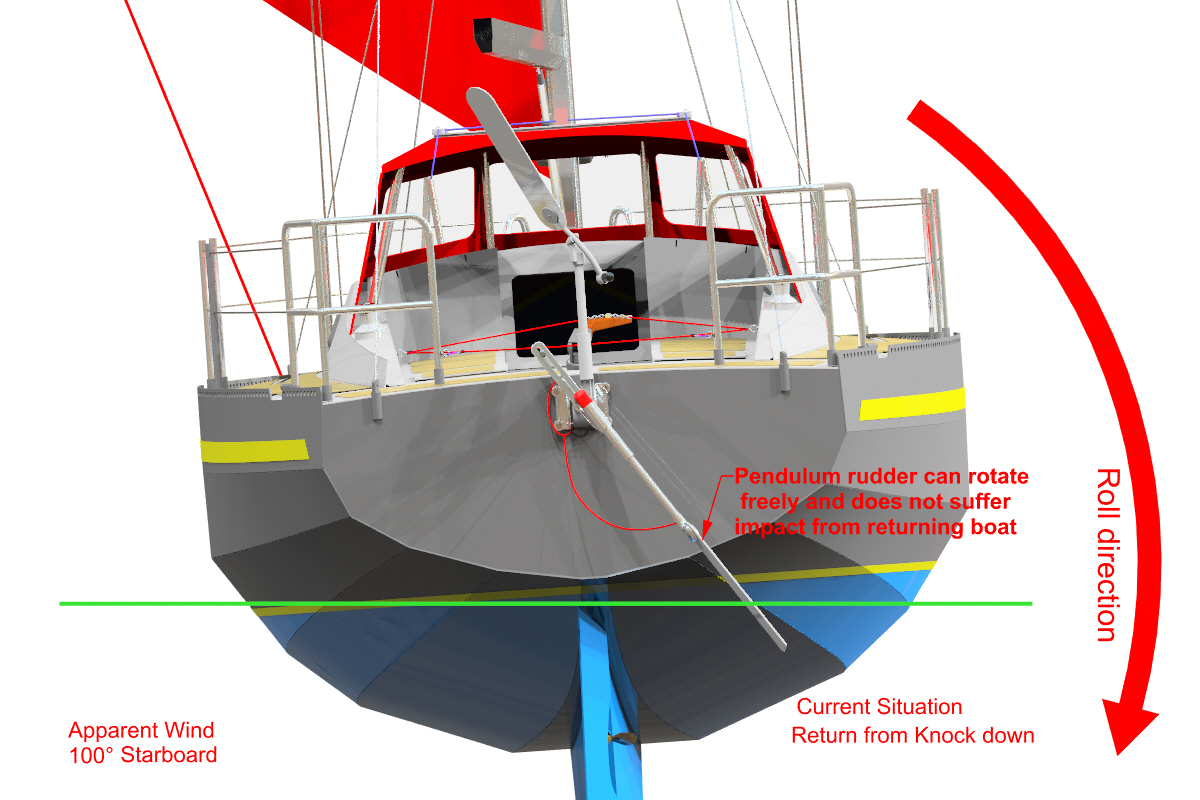

The design of the Windpilot systems renders any separate lateral overload protection in the form a designated point of failure unnecessary. This is because the lines that transmit the steering force to the tiller or wheel are attached at the top (rather than towards the bottom) of the pendulum arm, which is consequently free to move through an arc of 270 degrees (traditional systems are limited to about 60 degrees).

Sudden, erratic movements of the boat of the type to be expected in a capsize might still push the pendulum arm forcefully to the side, but there is nothing in the way for it to hit and damage (or be damaged by): it can travel through a whole 170 degrees to port and 100 degrees to starboard before reaching the end stops, but in reality the drag of the tiller or wheel to which it is harnessed will take the venom out of the rotational movement progressively before it reaches this point. As it happens, the transmission lines linking the vanegear to the steering themselves provide another level of overload protection (block lashings specced to fail first), as does the friction plate mechanism used in the wheel adaptor for wheel steering systems.

Abhilash Tomy was knocked down several times and lost both masts. His WSS survived intact

Istvan Kopar sailed through twelve storms with winds in excess of 50 kn and was knocked down three times. His WSS survived intact.

Tapio Lehtinen WSS intact

Antoine Cousot WSS intact

Igor Zaretskiy WSS intact

All five Windpilot sailors were provided with a complete spare system. None were needed.

Many thousands of examples of my Pacific model have gone forth from our factory in Hamburg since we introduced it 34 years ago, so it came as a relief as well as a pleasure to see the evidence of the GGR confirm the decisions I made when I was designing it. I have no idea how many of our pendulum rudder shafts have been all the way around the world, but I have never heard of a single one failing.

5 SKIPPERS RETIRED DUE TO PROBLEMS WITH WSS

Nabil Amra, broken BEAUFORT

Francesco Cappelletti, broken BEAUFORT

Philippe Péché,broken BEAUFORT

Are Wiig, MONITOR, multiple broken safety tubes (overload protection), knock down

Susie Goodall, MONITOR, multiple broken safety tubes (overload protection), interference between JSD and WSS and overload protection tripped, pitchpole.

CONCLUSIONS

The organizer decided to remove Monitor’s approved equipment status for the next GGR following the experiences of Susie and Are, but then changed his mind in April 2019 after the manufacturer apparently beefed up the design of certain parts. Given the issues raised above, however, it seems reasonable to ask whether stronger components alone are really the answer. The same excessive loads will still be encountered, it’s just that now they will have to be absorbed by different components – or the mounting system. The inherently limited arc of travel for the pendulum arm on the Aries and Monitor systems (no more than about 60 degrees in total) inevitably makes them susceptible to damage whenever there is a sudden exceptional increase in the angle of heel (as in a knock down, for example). If the pendulum arm hits the end stops hard, which is not improbable, the likely result is that the protective mechanism will be tripped or (and/or) something will break. Hydrovane systems have no servo-pendulum rudder, of course, but their reliance on shear pins makes them similarly vulnerable: if the pin does its job and shears, the system is then out of action pending a difficult repair even if, like Jean-Luc, the skipper has been smart enough to ensure the rudder stays with the boat.

All WSS, irrespective of manufacturer or design, can suffer damage that necessitates repair and recommissioning (for example due to flotsam, seagrass, whales, broken lines or failed blocks). Access to some kind of self-steering is of fundamental importance for the personal safety of competitors in the GGR. The ban on the use of electronic autopilots as a backup self-steering option reduces competitor safety and I consider it to be unjustified and unjustifiable. Originally conceived to protect the mechanical workings of WSS, designated points of failure can pose a significant threat to safety in an event like the GGR. If design no longer matches use, a rethink is required.

AND ANOTHER THING…

WSS are inevitably of critical importance for the GGR. When the original race took place 50 years ago, the technology was still in its infancy and Robin Knox-Johnston and Bernard Moitessier will probably not have been surprised at the need for alternatives to fall back on (either making the most of their boats’ natural propensity to sail straight or even – whisper it – steering by hand). Little development work had been done at that time in key areas like damping and leverage, so the systems available to them were pretty rudimentary.

If we applied the “if it was not on Suhaili, you cannot use it” principle strictly, none of the WSS featured in the recent edition would have been allowed. And yet the event is unimaginable without them. Notwithstanding the perfectly valid pursuit of historical authenticity, the GGR rules have been adapted in many ways to comply with/give way to modern expectations of event safety. Every boat was required to have multiple options for emergency communication, for instance, and while it’s possible these measures were essential in order for the race to be allowed to proceed (from the point of view of liability), they obviously make good sense from a safety perspective too.

The absolute ban on electronic backup for windvane self-steering systems turned their performance and limitations into an even more decisive factor in the race, with weaknesses in design and/or construction dooming a number of campaigns. Vanegear manufacturers find themselves stuck between a rock and hard place: GGR competitors need self-steering and if there are going to be WSS in the race, manufacturers will naturally want their products to be there on the start line, but there is a huge element of risk involved in exposing equipment that was never intended for racing at high latitudes to the trials of an event like the GGR.

The issues raised in this report are not new, not by any means, and should be very familiar to anyone thinking of organising a solo round-the-world race – especially if they have first-hand experience of their own. The race organiser’s decision to take on a manufacturer of WSS as a principal sponsor put his own neutrality in question throughout the event. The quite unnecessary conflict of interests created cast a long shadow over all of the event’s media output.

A comparison of the GGR and LLR lays bare the safety consequences of arbitrary rules like the ban on autopilots for redundancy, especially as everyone must now surely realise that WSS have been deployed in a role for which they are neither intended nor suited.

Trying to use the GGR as a marketing opportunity for WSS is like a game of Russian roulette for all concerned. Manufacturers don’t design and build their systems for this type of use, so the outcome – be it priceless publicity, total disaster or something in between the two – is to a considerable extent in the lap of the gods. The sailors – and the organiser who depends on them for his event (and all the more so if his own fortunes are tied up with those of a specific manufacturer) – are likewise left to labour under the sword of Damocles.

Some days you are the dog, some days the lamppost. The GGR cast me in the role of lamppost far, far too often for my liking, but now that the daily reports have finished and hard facts are starting to find their way into the public domain, a different, more nuanced and potentially more troubling picture – for all involved – is beginning to emerge.

05.july 2019

Peter Foerthmann

A good read.

Dear Peter,

another great article!

All I would want to say is, if I had to do the GGR all over again, I would choose the WindPilot. I am very confident of WindPilot. I had to change the linking rod once and change the lines once or maybe twice. No other issues during 12000 miles of sailing!

As I wrote to you earlier: My boat suffered violent knockdowns in a very bad storm on 21 Sep. Almost everything standing above deck was wiped out. The only piece of equipment that remained untouched was the WindPilot. It came through the storm and knockdowns almost untouched! I think one huge reason for this could be the fact that the blade is not restricted in its movement to either side.

The best part about Windpilot is, this goes without saying, Marzena and you! It has been an absolute pleasure working with you!

Warm regards

Abhilash

A very impressive Article, filled with facts and technical details, so important in a wilderness of subjective opinion, and sometimes misinformation.

The honest appraisal of what windvanes can and cannot provide, where their strengths and weaknesses lie, is a credit to the Peter who has long had a reputation as a straight shooter.

Love the new diagrams which make it clear what can happen to windvanes with hard side stops or shear pins in severe conditions. These weaknesses were blatantly exposed in the last GGR. The fact that this was not openly acknowledged by much of the media coverage is a shame, as it prevents learning by the offshore sailing community, including the manufacturers.

Autopilots as a backup for high-latitude, single handed sailors would certainly be a very sensible idea. Perhaps an obligation, given the experience during the last race. My personal experience is that APs don’t perform as well in most difficult conditions, but as a temporary backup to the primary windvane, they should not be ignored.

Keep up the work.

Oliver

Again a very clear explanation with excellent diagrams by Peter, to tell us high latitude long-distance sailors on how things work. It tells you all the detail that goes into the design of modern WSS systems. Having developed from huge appendages hanging of the back of transom by way of medium sized systems to an efficient, compact, light, strong and powerful pendulum concept.

As high latitude sailors it is even more important that one does not have to hang down over the transom to sheer in new lines or replace shear pins or worse. Without gloves your fingers would be stiff in minutes. We sailed the Arctic, the NW passage and crossed the Drake Passage to Antarctica 22 times. We never worried if the Windpilot would get through the ordeal when hit by bad weather. The pictures of Abhilash Tomy’s boat after the knock down say it all. And if the Windpilot needed any tweaking or new steering lines things could be done easily from the aft deck without any Houdini acts.

If the innovative Dutch designer of boats like the Maltese Falcon, Gerard Dijkstra, chooses a Windpilot for his own 53 footer then one can be sure there is no better WSS around.

Mark van de Weg

SY Jonathan

Peter, I do like your windvane report and I think it is good for the sailing comunity and possible new entrants for races like this.

As you know I have sailed over 50.000 miles under Windpilot and I am happy with it. I also have sailed over 30.000 miles with Aries and 15.000 with Hydrovane. It is a personal choise on what system suits most and I think it must be the sole rsponsibility of the skipper to choose his system.

All systems can have problems when used wrong. Windpilot can have a of line penduleme Aries can have problems with lifting the pendulem and on my Hydrovane I bend the rudder stock on a 28 ft boat. I think it is important for a race that the organizers can speak free aboat all systems and you have to choose sponsors without conflicts in this respect.

With kind regards,

Dick Koopmans

Great post! Of course I agree with what is in it, as I was the originator of the diagrams, and it becomes so clear when you understand the problem!

I am a cruising sailor relying on WSS as main steering aid when sailing, with a good hydraulic autopilot for back up and motoring, for 23 years now. I have sailed extensively with different types of hulls and WSS models, first with an Aries, from Brazil to Australia and after around the Pacific Islands, and hands on experience led me to decide for the Pacific model from Windpilot.

The Aries served me well, but I could see the design ideas that would make a difference after I got out there and saw other boats. Experience confirmed it, and now I have used a Pacific in boats as different as an 11m aluminum swing keel and twin rudder yacht from my own drafting board and a Hallberg-Rassy Monsoon 31, and would not go to sea without one for long passages now.

Even though I have not sailed myself in the Southern Ocean with an WSS, I have spent many months down there, from the 40 S to the 78 S latitudes as captain aboard the ships from eco NGO Sea Shepherd.

Working as a naval designer, stability calculations and assessment of seaworthiness are part of my daily duty, so I know when our assumptions break down and the breaking waves produce catastrophic dynamic movements, and these slow boats are specially vulnerable if left to lie motionless with a bad attitude to the incoming waves, and here Peter´s suggestion for back up is valuable.

Following the whole story I can confirm what Peter says about the 2:1 reduction gear that caused Istvan Kopar´s problems from the start. I had such a reduction in my first boat, and no matter what I did, my Aries would not steer it, to the point that after the first long passage, I modified the gear to eliminate the reduction, and that made it to work, but not yet to my contentment. Only when I installed a permanent short tiller on my center cockpit boat steering became reliable, and I attribute this to the extra friction the lines suffer in this type of unit.

I was excited about the GGR, I even contacted Don, as I considered participating in the next GGR, and could see that naturally WSS would make or break the race for most, so I was surprised to see that there was a WSS brand as official sponsor and rules made to induce its choice. It is not a question here of diminishing the superb effort made by the organizers to bring us this event, just a comment that I think this decision should be left to the skipper´s judgement. I understand the concerns about safety, but we have to assume that anyone daring to take this challenge must be able to take care of himself/herself, and limiting or inducing choices in WSS I believe was a mistake.

Also I think the sailing media showed lack of acumen in not getting into this exciting topic of self steering, which comes obviously to mind on a single handler´s race, and no serious discussion was attempted.

There were such reports into dismastings, capsizes, but self steering was seldom mentioned. Peter covered the gap due to his obvious need.

Lisboa 16th of july

Luis Manuel Pinho

SY Teresa

Hello Peter,

your effort to point out the facts about various windvanes is sharp as a knife. Inquisitive minds will surely get a lot of value from your observations.

My opinion about this last blog is that the obvious is out there for everyone who is seeking honest info.

Yet Again. We know that you and your brand is the source for understanding and getting honest information for many decades and with regard to the sailors worldwide I personally do hope that your company will provide this information many decades in future to come.

I think you have come to a sound conclusion:

Given the rules that are out there it could be a very sensible and logical step to put in a redundant system for emergency steering too.-

As Don always says, the GGR belongs the most to the people who are committed racing it.

So if the entrants of 2022 unite in such sensible form of extra safety, it can be a possible extra feature of the race.

It can be surely a possibility to organise a redundant steering system to avoid entrants running into acute trouble if the windvane stops working in make or break circumstances.

I do hope that in future more entrants will succeed in finishing the race. The finishers are profound ambassadors for long distance sailing and true examples for their fans and generations to come and it can only be a good thing to share sailing adventures about the savage beauty of our blue planet to people at home.

Keep up the good work, sharing of your opinion makes a lot of difference for sailors looking for the best system for their needs.

And probably in a lot of cases, sailors looking for information get a lot of information they did not realize before about their needs simply by reading your blogs.

All the Best,

Mirjam and Eli

The ban on the use of electronic autopilots as a backup self-steering option reduces competitor safety and I consider it to be unjustified and unjustifiable.” I agree about this – I only have vane gear on board at the moment and I wish I had a tiller pilot – there are many cases where this is so useful, and I know you know them, but in my case I will be crossing Biscay, and if I encounter a weather window that has very light air I am the sort of person who will put the motor on and get across rather than wait for wind and possible bad weather on this piece of water. A tiller pilot would be so useful in such a case – motoring for >100 miles for example.

br Luke

There is nothing more to add to these testimonies and experience reports. It is as it is and Peter, you have studied it for a long time, understood it and implemented it consistently.

Hi Peter,

This was a great read – very informative. It seems you are moving on from your experience with the GGR. I think I might be starting to as well!

I have just completed glassing in a new bulkhead up forward, one of the big jobs I had to do to before floating.

I am very impressed by your windpilot.

Cheers, Tim Newson

Just by chance 2 days ago we looked at the movie „Deep water“ featuring the “original” Golden Globe Race (albeit with emphasis on the “participation” of Donald Crowhurst) & now I read Peters blog here.

What audacity to call last year’s strange “reenactment” “Golden Globe race” too, implying that it was in the same spirit & it’s participants of the same mettle as those of the original one from 68. No wonder it attracted an above average number of characters particularly ill-suited for a nonstop singlehanded circumnavigation, racing to boot. (What VdH found exciting enough about the whole setup I cannot understand)

Neither the spirit was the same: the ‘68 race was run with the best boats & equipment that the participants could afford, not a “nostalgic” event with “approved designs”, nor is the mettle of most of the recent crop of GGR- racers of the same order, everybody judge themselves: “singlehanded racers” that couldn’t get their windvane selfsteering gears to steer their long keeled boats because the mechanisms were too “complex” for them…participants not going to the trouble of trial runs with their windvanes (& worse: blaming their failures on their Windpilots! A selfsteering gear that has a huge number of circumnavigations to its credit), racers retiring because they couldn’t stand the loneliness.

The whole concept of such a “reenactment” race seems nutty to me. Who would want to be treated according to the medical standards of the sixties, surgical techniques, medicines & all. Time has moved on & only Don Quixote would attempt to turn back it’s wheel. (Sure it was so much more exciting & satisfying finding your way with the sextant in the “old days” – but this is gone & cannot be recaptured by sealing the “emergency GPS chartplotter” in a box. [adventure, yes! But safety net please!])The original GGRacers were legends in their own lifetimes (did they sail “approved designs”?), movies have been made about their endeavor, RKJ has been knighted (“There will always be someone faster, but there will only ever be one first!”), one cannot “latch onto their fame” participating (yeah, with a sealed GPS chartplotter & approved designs…) in the “reenactment”.

The 2022 GGR is even going one better: they are going to have a Joshua One design class (the builders can’t even get the name right on their website…): the hull seems to have chines…! Somebody seems to be making fun of Bernhard Moitessier.

But then, as a dyed-in-the-wool cruiser (3 rtw & 1x France to Tahiti, all on the Tradewind route) I fail to understand the concept of sailracing at all: some “race comitee” fixes departure time & destination & I “obey”???

Just my 2 cents worth

Wolfgang Wappl, SY Imagine, Tahiti

(for the record: 1rtw with Aries, 2 rtw with Atoms, Bretagne-Tahiti Windpilot Pacific)

Sailboat races are exciting! Since the first round the world race (won by Sir RKJ after Bernard Moitessier decided to skip the finish and carry on sailing “la longue route”), lots of sponsors have come in to promote transatlantic, transcontinental and round the world events. Nowadays stunning boats like Class 40s, foiling Imocas and Ultimes race around the planet. Promoting a competition to sail around world like “old times” for me makes no sense. If we look carefully, the last GGR 2018, which was intended to reproduce old times, was a failure. Recent boats built with new technology, including using furler systems (however penalized in time), but with self-steering gear that (in some cases) hasn´t changed in decades… It´s amazing! The worst was that emergency backups like electronic autopilots, GPS, satellite facilities was forbidden. What is the reason? To play with human life? Also, most of these sailors had no experience with blue water, never mind at the dangerous high latitudes, so what we saw was a fight to survive. The organisers had a lot of luck nobody lost their life. One of these competitors, Jean Luc VDH, is one of the most qualified blue water racers and was the overall winner. This was clear before the start! In his excellent article, Peter Foerthmann describes in detail the behaviour of a sailboat during a storm and what happens with a self-steering gear at the transom. Looking at the results, only boats with Windpilot steering gear recovered from a knockdown without damage to the gear. The article explains why. Finally, it must be emphasized that Windpilot and the other self-steering systems were not built for racing around the world!

Jayme Santos Souza onboard SY Epa

Rabat, Morocco

This GGR report is very interesting and the analysis very much relevant.

To this subject I would like to add my personal testimony: in august 2017 while crossing the south indian ocean westward, we (my wife and I) experienced a knockdown while sailing in heavy weather and crossed seas under windpilot. Though we had a few damages (dodger sheared-off and main stay attachment disloged), when the boat adjusted back to a normal angle, the windpilot put us back on our route rapidly! It did the job very well without being damaged.

With kind regards

Laurent & Shu-In

S/Y Galatée

The fact that a manufacturer takes so much effort and pride in his work is in itself remarkable. This in the light of most companies after they have done the deal/sold their product leave the customer in the dark!

Not only is this article very interesting from a technical point of view but also previous articles related to the GGR are a good read because the humanity comes into play. I was somewhat shocked to learn that in “our sailing community“ good behavior is not for granted.

A great deal of stubbornness and endurance is needed to share those knowledge and wisdom learned “the hard way“.

Thanks for that Peter!

I have been very happy with both reliability and performance of my Windpilot during my 322 day solo circumnavigation in the Golden Globe Race 2018. I have used an inside pedal steering system on Asteria during some extreme circumstances with steepest seas and strongest winds to help the WP to keep Asterias running down steep waves, about 20 degrees off dead downwind. I might have been a bit luckier with the worst weathers encountered than some of my competitors, i.e. due to my Sparkman & Stephens designed Gaia 36´s extreme seaworthyness. and her bottom covered with barnackles provided me a handbrake without trailing warps (but not increasing directional stability). Difficult to analyze, but certainly I didn’t have any problems in the worst weathers caused by my wind vane. I had a habit of hitting the sack after shortening sail down to the storm jib and having the boat shipshape in order to be fit for fight myself if the going would get seriously rough. I think I slept through a couple of the worst storms this way with Windpilot steering the boat.

Tapio Lehtinen

SY ASTERIA

Peter,

Thanks for the interesting reading and included information. All the good points of your Windpilot steering system have been discussed at length and there is no need for me to replicate them. The wind and seas have not changed and likewise the physics of pendulum windvane steering have not changed. What has changed though is the application of stronger and lighter materials, lowered friction, better corrosion resistance, ease of maintenance, ease of repairs, ease of removal. All resulting in better and more reliable windvane steering gears.

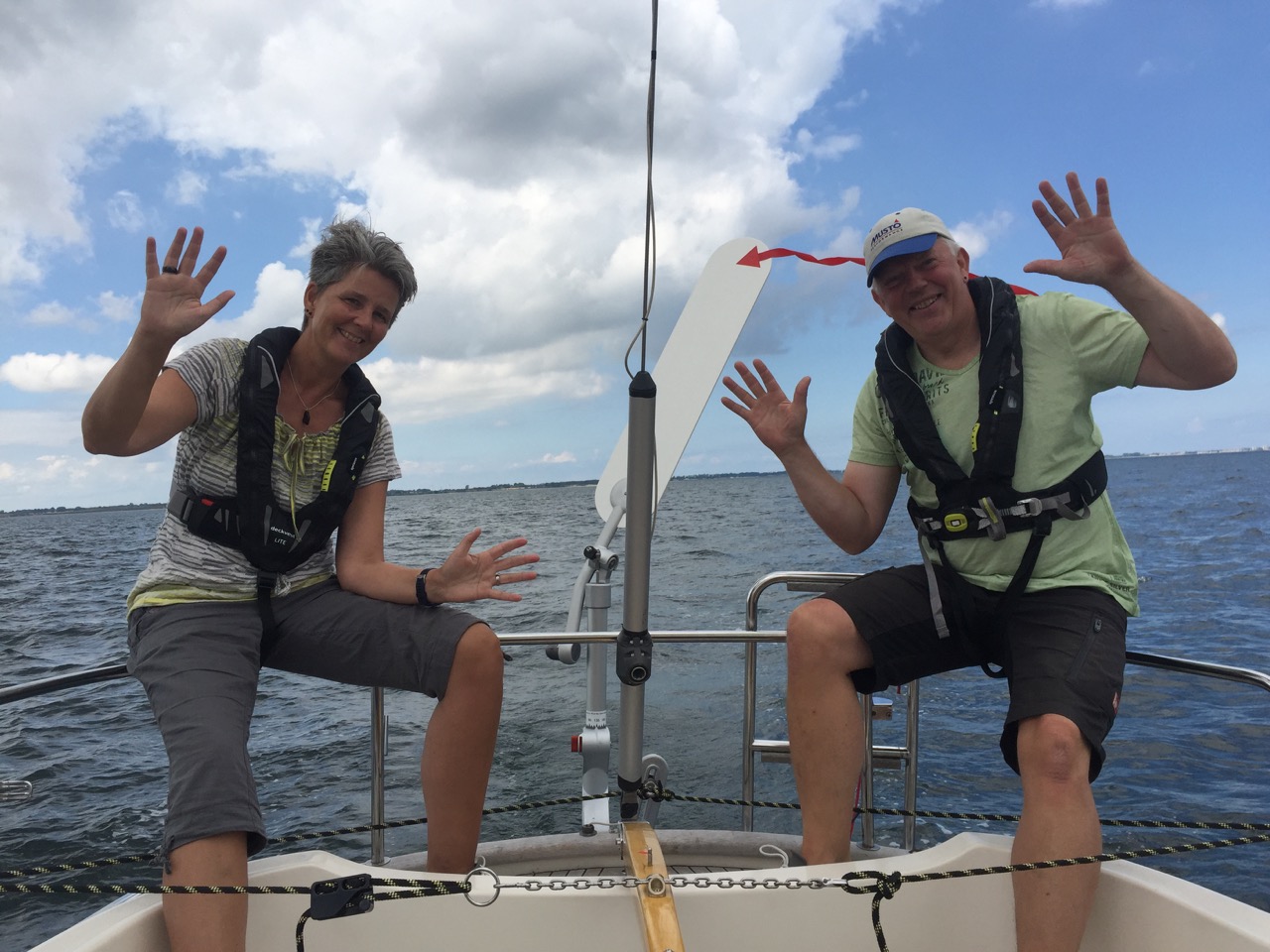

Windpilot has certainly been one of the leaders in this development, if not the major one. I did fit a pendulum vane (Atoms) in 1976 to the 50 ft Bestevaer and in 2003 I did fit a pendulum vane (Windpilot) to the 53 ft Bestevaer 2. Now, in 2019, the vane is still there and as good as ever. I am very pleased that you use a photo of this gear, taken onboard Bestevaer 2 during her maiden voyage, in your header to this blog. I must admit that on both boats I did – and do use an AP as well. Both systems have their strong points. Thank you for your contribution to making my life at sea more comfortable, or should I say, thanks for making my life at sea less of an hardship.

Fair winds,

Gerard Dijkstra

PS And Peter, remember, there are still people out there who think the earth is flat.

Hello Peter,

Again an accurate publication. As you know, on Trotamar 3 we had three different windvane selfsteering gears till I decided for the Pacific Plus. We crossed 4 times the Atlantic and the last time followed by the hurricane Bonny with 12 m waves and always with the Windpilot steering the boat. Now I am installing the new Windpilot on Trotamar 4 and will test it in the next weeks.

Hope to see you again in Hamburg or anywhere else, fair winds,

Joan, Trotamar 4

Lerhaps if every 2022 GGR participant agreed to break the seal on their electric autopilot, GGR would have to reconsider their position (or have zero “winners/completors”).

I enjoyed your analysis of windvane fundamentals and summary of how they performed in the GGR. During the race I was astonished at how most of the sailors pressed on in heavy weather. In the 1968 race, Moitessier certainly pressed on harder than Knox-Johnston, but even he reefed early and hand steered at times. Joshua was bulletproof, which helped, and his trim-tab self steering gear, similar to the unit I sailed with for 20 years, was indestructible. But even if the sailors were not allowing competitiveness to compromise seamanship, which I felt most of the GGR 2018 fleet were, one has to consider the design of contemporary windvane units. I have made passages with an older Aries and an earlier model Flemming Minor. The Aries was just used for tradewind sailing but I still worried about the inaccessible pendulum and the way it slammed at times in a cross sea. I must admit I was younger then, less experienced and too gung-ho. These day I work harder to keep the boat balanced and even occasionally (shudder) resort to hand steering. Another time, lying ahull in the Tasman Sea in a gale with the Flemming, we bent one of the pushrods between the vane and the pendulum. Talking about it years later with Kevin Flemming, he said I should have contacted him and he would have sent a replacement, since they had discovered the original rod was too weak. Fair enough, but when I came to build my dream boat, I fitted a robust trim tab on the external rudder and lived happily ever after. I never took it into the Southern Ocean though. Having sailed there once, from the South Island of New Zealand to Tahiti, I prefer not to. Until now, I have been unwilling to use a servo pendulum model again, but your explanation of how Windpilot has met the challenge of the pendulum slamming against its stops (by not having any), and the subsequent ease of swinging the blade up out of the water while standing (or kneeling) on the deck, has led me to decide I will fit a Windpilot to my current boat, which has an inboard rudder. Servo pendulum gears are undoubtedly more powerful than trim tab units, and now we have a unit that overcomes their inherent design weaknesses. I was considering an auxiliary rudder, but my transom is not strong enough and the risk of damage to the unit too high as well. Thank you for this illuminating report.

Reading this report reminds me of Blondie Hasler’s experience with Francis Chichester and Gypsy Moth 1V, during the latter’s circumnavigation in 1966-7. Blondie and Francis knew each other well of course, both having sailed the first two OSTARs, a 3000NM race predominantly to windward, across the North Atlantic. In 1960, Francis won aboard his 12m bermudian sloop, in a time of 40 days, coming in wet, disheveled and almost incoherent with exhaustion. Blondie arrived eight days later on his 7.6m junk-rigged Folkboat, well rested, shaved, wearing clean, fresh, dry clothes, and ready for some stimulating conversation.

After Eric Tabarly won the 1964 OSTAR, Chichester’s wealthy cousin offered to pay for a new boat that could win the 1968 race. Illingworth and Primrose designed Gypsy Moth 1V to excel in this primarily windward race, and Francis asked Blondie to provide one of his new servo-pendulum self-steering units for the boat.

But what neither the boat’s designers or Blondie (and possibly the cousin) knew was that Francis had no intention of racing in the 1968 OSTAR. He intended to circumnavigate the world via the five Southern Capes, racing against the time of the Clipper ships. He kept it secret because he feared someone else might steal his idea. And he was right, because as soon as his intentions became clear, Alec Rose, a fellow 1964 OSTAR competitor, announced he was also going, and declared it a race. Of course, Alec’s boat was smaller and slower, but a faster competitor might have appeared given enough lead time. Francis wasn’t the only fiercely competitive horse in the ocean racing stable.

But the problem with his secrecy is that he ended up with a boat that was not really suitable for running before the Southern Ocean westerlies, and Blondie said later that if he had known what Francis was up to he would have built him a larger, more robust, custom self-steering gear.

So off Francis went and had endless trouble with the boat and the self-steering. He spoke and wrote scathingly about both in the years that followed, which must have done untold damage to the brand names of parties involved. It is possibly no coincidence that Hasler windvane gears were soon eclipsed by Nick Franklin’s Aries unit.

Bonsoir Peter,

I found your technical article about the GGR report very interesting and the analysis very much relevant.

To this subject I would like to add my personal testimony: in august 2017 while crossing the south indian ocean westward, we (my wife and I) experienced a knockdown while sailing in heavy weather and crossed seas under windpilot. Though we had a few damages (dodger sheared-off and main stay attachment disloged), when the boat adjusted back to a normal angle, the windpilot put us back on our route rapidly! It did the job very well without being damaged.

With kind regards

Laurent & Shu-In

S/Y Galatée

Thank you Peter,

I have not really been following the GGR, but I did hear that one of the competitors had an issue with his Windpilot. In English we would say ‘A poor workman blames his tools.’ Of course wheel steering is always a little bit problematical with windvane steering in my opinion. Tillers just make everything so easy.

I have been knocked down using both the Pacific Light and the Pacific, in all cases it was my fault for running before the wind when the waves were too big. My knockdowns occurred both in the North Atlantic and the Southern Ocean. In all cases not only did my Windpilots remain undamaged but my steering system was also completely undamaged. The North Atlantic knockdowns were with a spade rudder on my UFO27 and the Southern Ocean was a skeg hung rudder on my Rival 34.

I have included a picture of a Pigeon that trusts Windpilot more than his/her own sense of direction. Also a song that my Windpilot sings when she wants to annoy me. Both my Windpilots have been called ‘Miss Piggy’ after the tough Sesame Street Character who packed such a ‘Wallop’. The song Miss Piggy’s lament is based on an old Scottish ballad called ‘My Bonny lies over the Ocean.’

Danke,

John Apps, SV Glayva

Amazing.