CHICKENS COMING HOME TO ROOST?

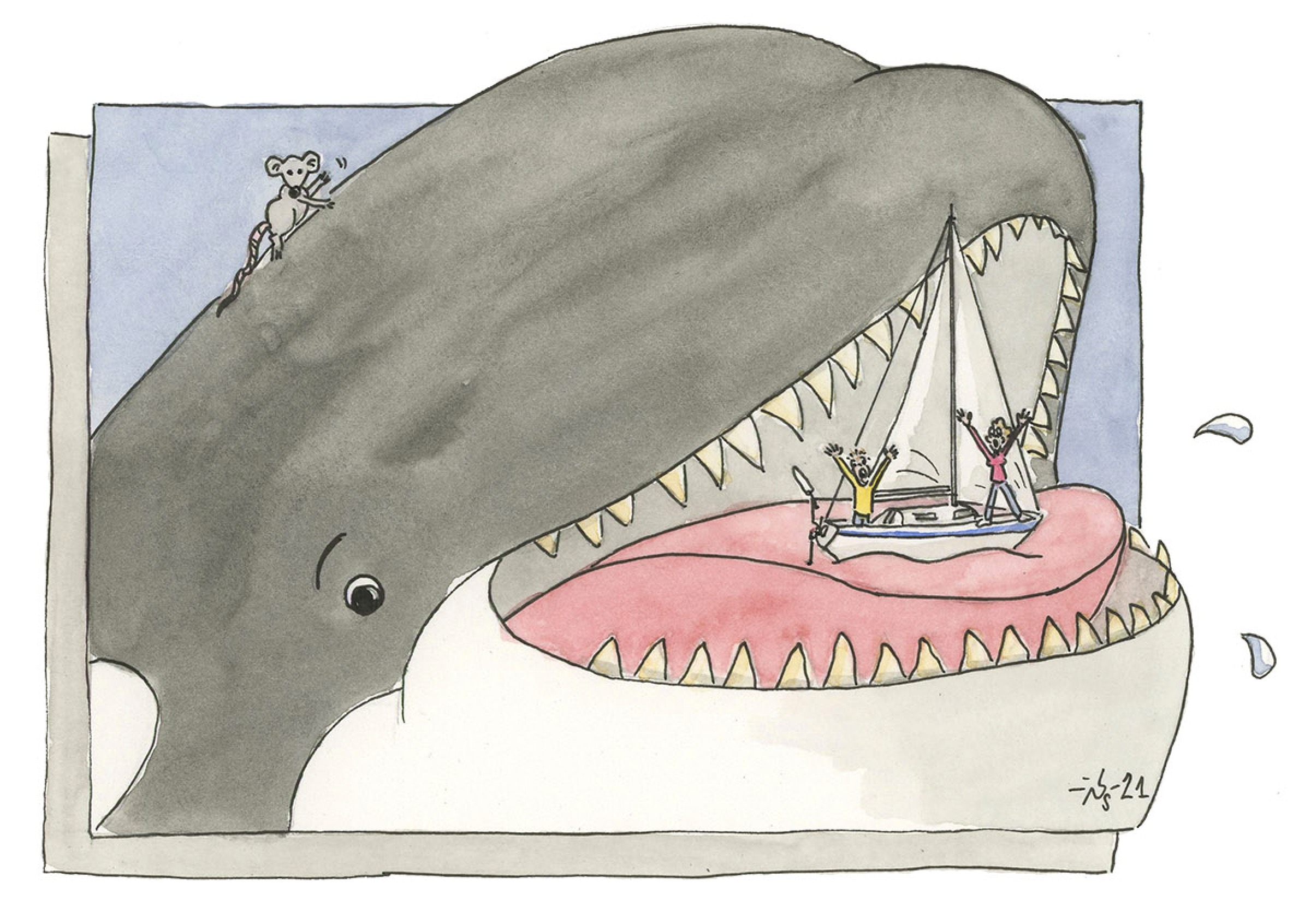

The fault probably lies with us: for too long we just wouldn’t see. This black-and-white superfish is no Flipper the friendly dolphin from TV, no kitchen-ready candidate for the filleting knife, parsley, capers and a drizzle of beurre noisette. The new terror from below is far more like the archetypal monster in the night: one never knows where it might be lurking or when it might take a fancy to the rudder and attack.

The fault probably lies with us: for too long we just wouldn’t see. This black-and-white superfish is no Flipper the friendly dolphin from TV, no kitchen-ready candidate for the filleting knife, parsley, capers and a drizzle of beurre noisette. The new terror from below is far more like the archetypal monster in the night: one never knows where it might be lurking or when it might take a fancy to the rudder and attack.

We have tended to view orcas as friendly, almost cuddly creatures in the main, one half of a double act with an equally aesthetically pleasing water nymph of a human “trainer” whose firm instructions would send them racing off to perform breath-taking tricks in and over their pitifully small pool for the pleasure – and soaking – of a paying audience unconcerned with the realities of captive cetacean existence. Our perceptions distorted by TV shows and dolphinariums, we perhaps lost sight of their true nature. Now though we can see the folly of our misjudgement; now they have started taking liberties with our toys.

We have tended to view orcas as friendly, almost cuddly creatures in the main, one half of a double act with an equally aesthetically pleasing water nymph of a human “trainer” whose firm instructions would send them racing off to perform breath-taking tricks in and over their pitifully small pool for the pleasure – and soaking – of a paying audience unconcerned with the realities of captive cetacean existence. Our perceptions distorted by TV shows and dolphinariums, we perhaps lost sight of their true nature. Now though we can see the folly of our misjudgement; now they have started taking liberties with our toys.

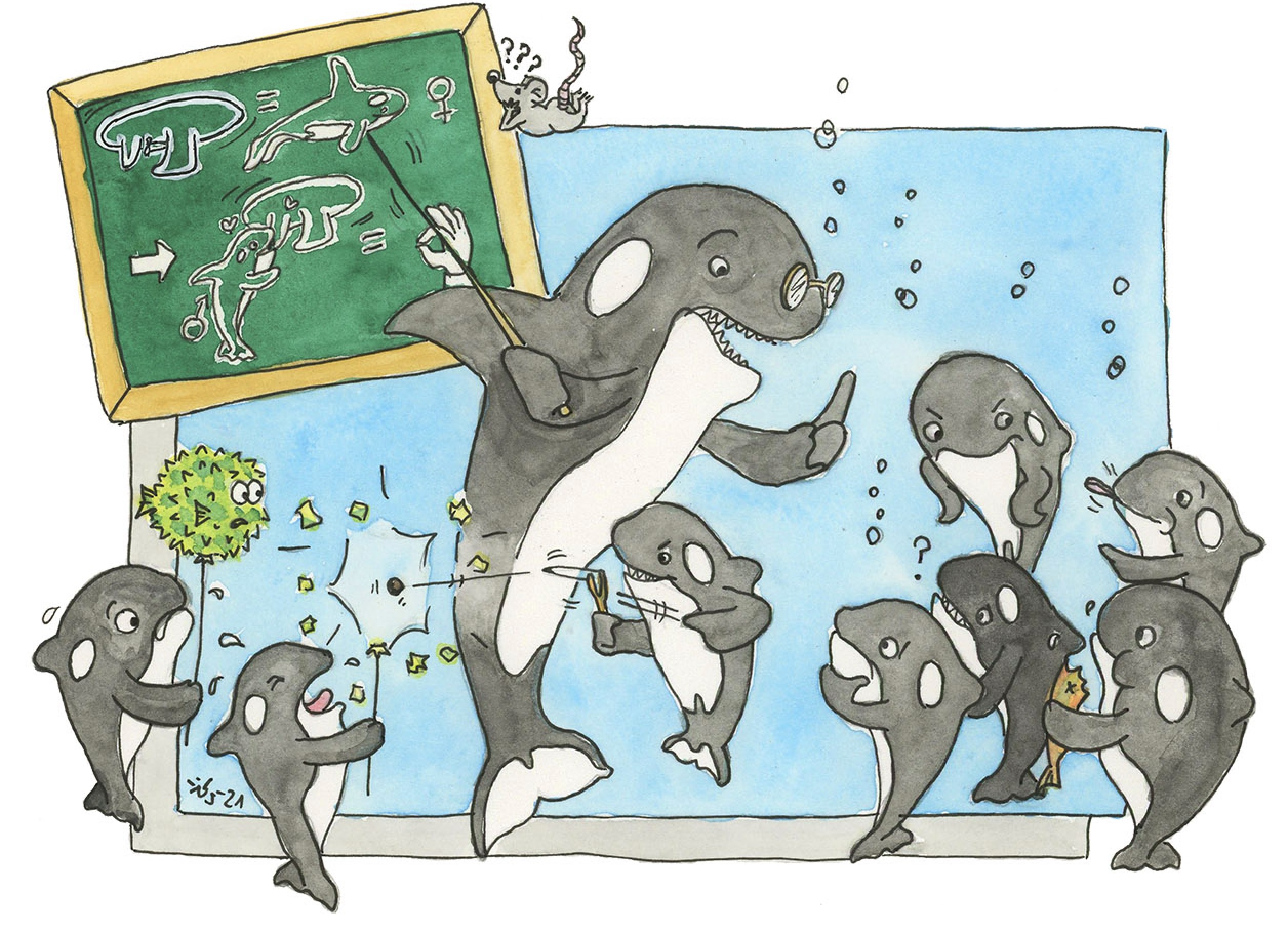

Thanks to heavy media coverage and herds of dutiful YouTube disciples, we now find ourselves waiting on tenterhooks for news, for some somnambular professor (for example) to poke us with the facts we don’t want to hear even though somewhere deep down we already know them to be true (albeit too dreadful to acknowledge openly). Is nobody prepared to speak first? So be it. I will dare to utter the unspeakable: our misjudgement of the orca has been fuelled by our own wilful deceptions.

Thanks to heavy media coverage and herds of dutiful YouTube disciples, we now find ourselves waiting on tenterhooks for news, for some somnambular professor (for example) to poke us with the facts we don’t want to hear even though somewhere deep down we already know them to be true (albeit too dreadful to acknowledge openly). Is nobody prepared to speak first? So be it. I will dare to utter the unspeakable: our misjudgement of the orca has been fuelled by our own wilful deceptions.

The truth of this mighty marine mammal could hardly be further removed from the image we have painted ourselves. It is threat incarnate. Huge, powerful and rapid, it can charm us with its toothy grin and make our hair stand on end with the force of its breath but it can also set our nerves a-jangle and turn a peaceful cruise into a (real or imagined) game of marine cat and mouse. It can ignore us, of course, or it can choose to expose our boats to the full range of its curiosity and imagination. Will it be happy just to nuzzle our keel – perhaps even content itself with sneezing on us – or is our tender hull about to experience a passionate romp orca-style with six tonnes of enthusiastic cetacean lover?

The truth of this mighty marine mammal could hardly be further removed from the image we have painted ourselves. It is threat incarnate. Huge, powerful and rapid, it can charm us with its toothy grin and make our hair stand on end with the force of its breath but it can also set our nerves a-jangle and turn a peaceful cruise into a (real or imagined) game of marine cat and mouse. It can ignore us, of course, or it can choose to expose our boats to the full range of its curiosity and imagination. Will it be happy just to nuzzle our keel – perhaps even content itself with sneezing on us – or is our tender hull about to experience a passionate romp orca-style with six tonnes of enthusiastic cetacean lover?

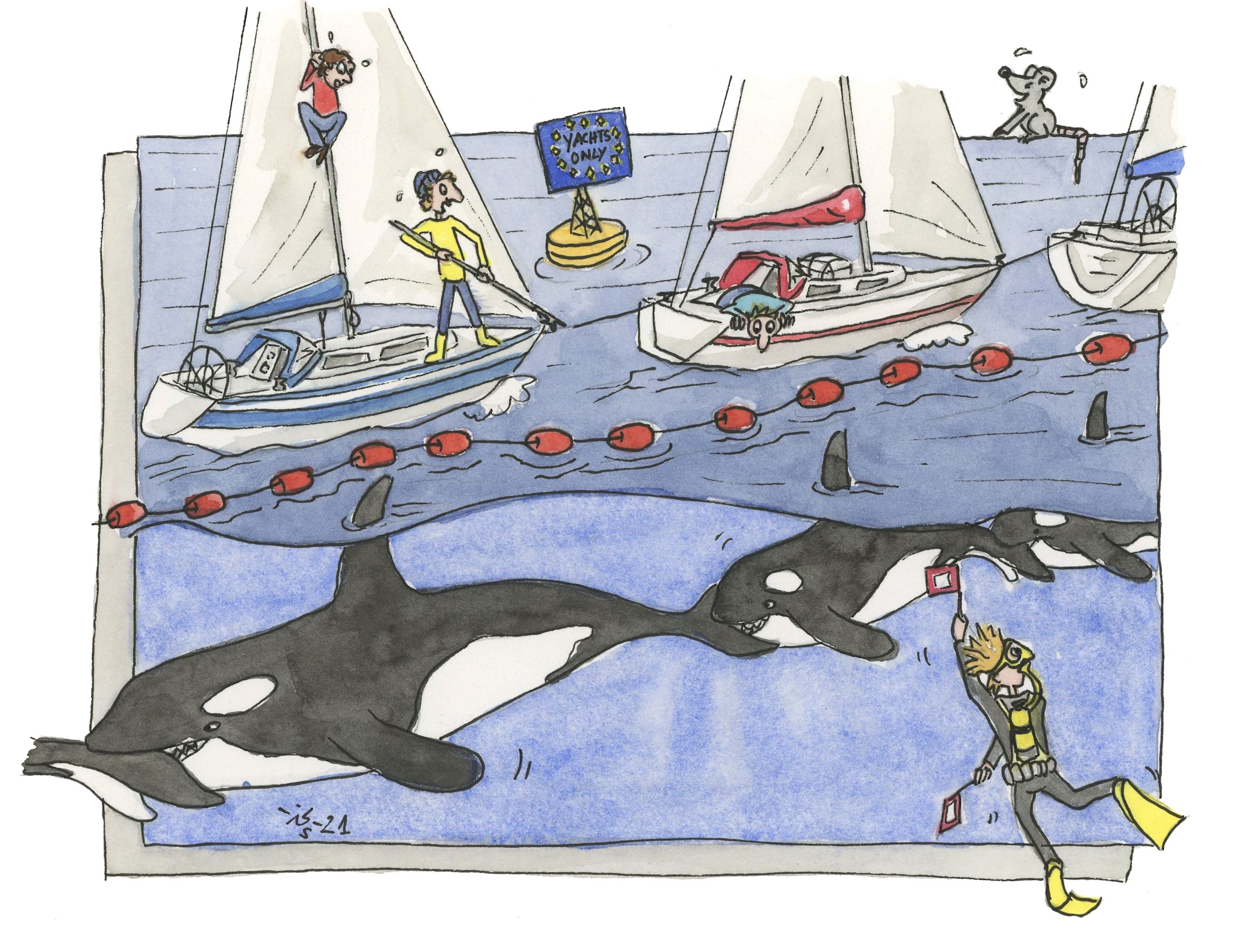

The prospect of a sudden meeting with a mobile black and white reef should give all sailors pause for thought, especially those venturing afloat with just a few millimetres of GRP shell between their feet and the wet stuff. It appears we have miscalculated – or perhaps we have just failed to contemplate the issues sufficiently and made do instead with telling ourselves it will all be OK. Have we gone too far in outsourcing our safety to classification organisations, boat-builders and insurance companies? Have we been asleep at the helm?

Anyway, it is high time we powered up the hindsight engine and set to work with the most pressing task at hand, namely exonerating ourselves and finding some vaguely plausible scapegoats to catch the flak on our behalf. Not that any of us would ever respond like that for real, of course!

Be all of that as it may, we do at least now have a better idea of the situation. A little research has taught us something of orca habits and identified the areas in which they have begun to take an unhealthy interest in shipping and, intentionally or otherwise, wreaked havoc on the occasional boat. Nobody likes a riddle they cannot solve. Although we are quite accustomed to hearing orcas described as “highly intelligent animals”, the unspoken assumption is that we are far more intelligent still. And if that is the case, ought we not to be able to understand what they are up to? We ought. Homo Sapiens makes the rules, follows reason before instinct, strives to figure out causes, explanations and workarounds. But can anyone, from scientist to psychic, think of any possible reason why humans and orcas should have come into conflict in that particular spot off the Iberian coast where fishing fleets jostle for a space haul their vast nets as their water bound fellow predators seek a belly-full for themselves?

Be all of that as it may, we do at least now have a better idea of the situation. A little research has taught us something of orca habits and identified the areas in which they have begun to take an unhealthy interest in shipping and, intentionally or otherwise, wreaked havoc on the occasional boat. Nobody likes a riddle they cannot solve. Although we are quite accustomed to hearing orcas described as “highly intelligent animals”, the unspoken assumption is that we are far more intelligent still. And if that is the case, ought we not to be able to understand what they are up to? We ought. Homo Sapiens makes the rules, follows reason before instinct, strives to figure out causes, explanations and workarounds. But can anyone, from scientist to psychic, think of any possible reason why humans and orcas should have come into conflict in that particular spot off the Iberian coast where fishing fleets jostle for a space haul their vast nets as their water bound fellow predators seek a belly-full for themselves?

It stands to reason orcas would object to seeing their supper swiped from their table so we perhaps should not be surprised to discover that (even without the help of social media to organise themselves) they have begun to do something about it. They must realise where the bounty goes, who drags it from the sea in bulging nets, what it is that fills the holds of those capacious trawlers and travelling factory ships shuttling back and forth between the shore and the fishing grounds and leaving little for the residents besides the scraps they throw back as unworthy. What compensation is unwanted bycatch for an orca that has seen the bounty of its home range hoovered up to meet the needs and desires of mankind? Hunger. Hunger is the main problem, exacerbated, we can assume, by the noise of sonar, engines and powerful propellers that pounds incessantly on the sensitive ears and nerves of ocean-dwelling organisms. Road rage under the water!

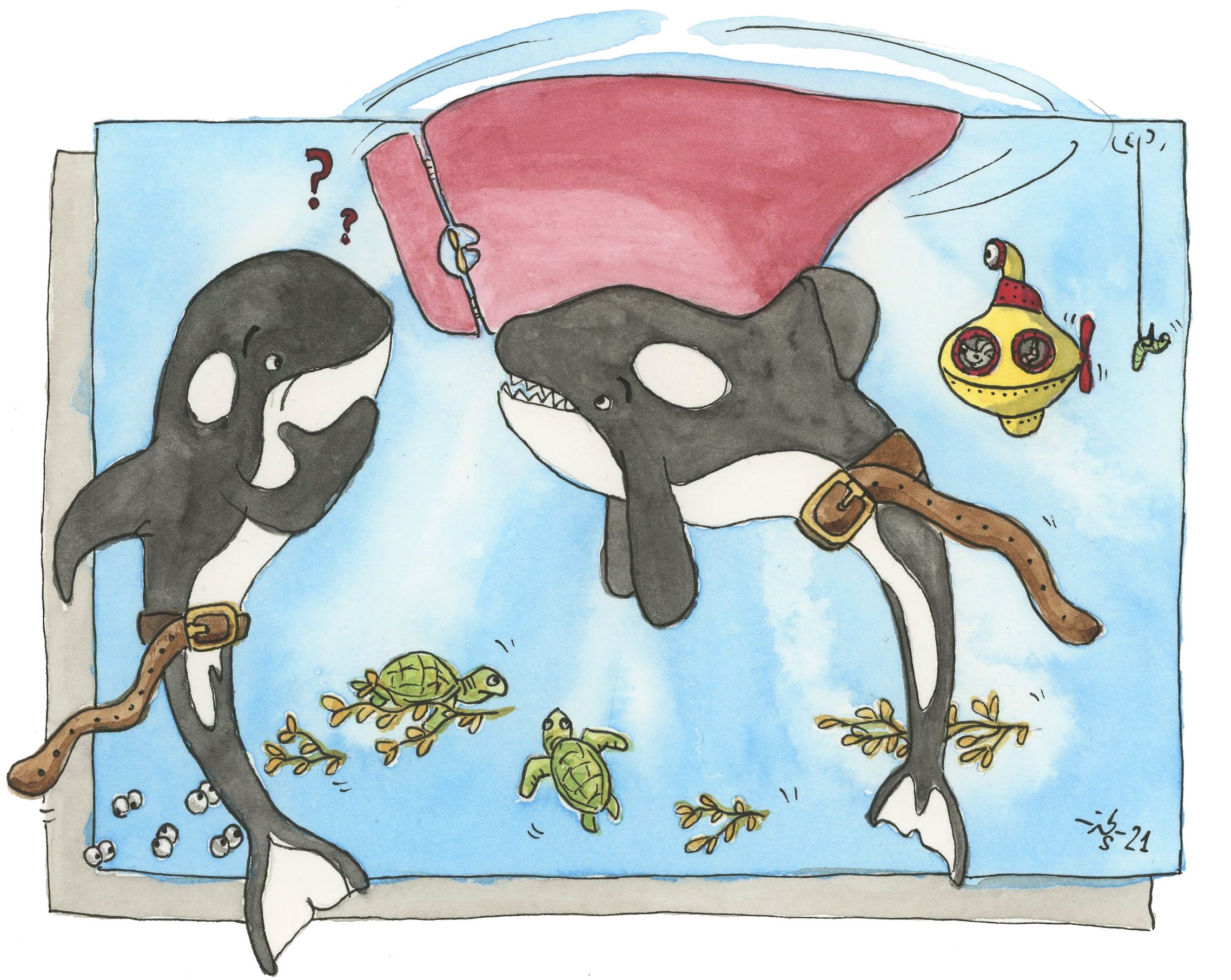

Fishermen in the bars along this coast know the drill: when the orcas come knocking on the hull, throwing some fish back for them is the way to restore peace. Not only does the fisherman understand how it works, but so does the orca – so why would it not try the same trick with sailing boats as well, especially since their silly upside-down dorsal fins make them so much fun to snuggle with? Rumours of amorous orcas – “Manolitos”, as they are known – seeking satisfaction from unconsenting ships have been swirling around harbourside taverns for some time. Confused marine mammal as overbearing sex pest? Or does it ultimately all just come down to too little food as a result of human overfishing?

Fishermen in the bars along this coast know the drill: when the orcas come knocking on the hull, throwing some fish back for them is the way to restore peace. Not only does the fisherman understand how it works, but so does the orca – so why would it not try the same trick with sailing boats as well, especially since their silly upside-down dorsal fins make them so much fun to snuggle with? Rumours of amorous orcas – “Manolitos”, as they are known – seeking satisfaction from unconsenting ships have been swirling around harbourside taverns for some time. Confused marine mammal as overbearing sex pest? Or does it ultimately all just come down to too little food as a result of human overfishing?

Finally the true gravity of the situation begins to come into focus. Fishing boats are among the toughest craft on the water. Built strong for a long working life in all weathers and sea states, they are the epitome of seaworthiness. Collisions with hungry sea creatures are nothing to trouble a fishing boat captain’s sleep – even being T-boned by the occasional errant IMOCA 60 seems to be no more than a minor inconvenience. Perhaps we should be comparing the orcas to wild boar rooting around beneath the oaks: the point is the food to be found, not the disturbance caused in the process.

Are our cruising yachts robust enough to withstand the attentions of foraging killer whales? Are good solid frames still the order of the day or has strength been compromised here and there to make more space for furniture and “living space” (and reduce costs into the bargain)? Scary thoughts! How, I wonder, can we go on considering ourselves the pinnacle of intelligence when we persist in putting to sea in vessels whose vulnerability is so obvious if only we are prepared to look. In truth the big rethink has already started in some quarters. The cogs have begun to turn, which is what prompted me to put my own thoughts on the matter on the record (that and the arrestingly shocking photos of ravaged pleasure craft that have recently gone viral). Does insurance cover orca damage? I do not know the answer to that but I am pretty sure it is the wrong question to be asking!

It surely cannot be the case that we are cross just because a particular sea creature is living its own life on its own terms and we can find nothing much to hold against it. The playful pied torpedo has shown us who really rules the waves once the last mooring line has been loosed. As dry land recedes towards the horizon, the true minuteness of yacht and crew becomes harder to ignore and the fear begins to grow: suddenly a whole family squadron of a life form we really know next to nothing about starts sporting around the floating nutshell home. Are they examining the potential catch to see if it is worth the effort? What do they make of the sunlight reflecting off the iPhones that have rapidly appeared on deck to record events for a later (assuming there is a later) upload and the chance of a few moments of social media fame?

It surely cannot be the case that we are cross just because a particular sea creature is living its own life on its own terms and we can find nothing much to hold against it. The playful pied torpedo has shown us who really rules the waves once the last mooring line has been loosed. As dry land recedes towards the horizon, the true minuteness of yacht and crew becomes harder to ignore and the fear begins to grow: suddenly a whole family squadron of a life form we really know next to nothing about starts sporting around the floating nutshell home. Are they examining the potential catch to see if it is worth the effort? What do they make of the sunlight reflecting off the iPhones that have rapidly appeared on deck to record events for a later (assuming there is a later) upload and the chance of a few moments of social media fame?

Whatever else the human witnesses to these encounters take from them, I’m certain they must learn a new, visceral respect for the orca. But does that stem from the sheer size and power of the animal, I wonder, or from the feeling of having played Russian roulette and won? Should somebody perhaps launch a survey to establish the real reasons? I doubt it can be that simple but now I think about it, in contemplating these ideas we may actually – almost inadvertently – have found our way to the truth of what it is about these mighty seafood-guzzling machines that troubles us so. Is it really them, or is it that their actions are forcing us to confront our own stupidity in having failed to give sufficient consideration to the strength of our vessels? By the way, a flotilla of eight yachts recently assembled in Sines, Portugal, waiting to be lifted out of the water by a mobile crane (with costs shared to minimise the pain). All had been left lame after orca encounters.

It seems plausible (at the very least) to suspect our fear has its roots in the realisation that we got it wrong: for too long we have blithely assumed that, the odd rogue container aside, the sea was essentially free of solid objects and that with our array of electronic gadgets to protect us, we had everything under control and could more or less guarantee our own safety even outside of rescue helicopter range. Sonar under the water, Oscar for flotsam, radar for the air above, repeater displays in the heads for complete control at all times… Add in AIS, chart plotter and depth sounder and we are omniscient in our world, masters of the universe. Or have we lulled ourselves into a false sense of security? Having installed every system and instrument money can buy to keep us safe at sea, should we not finally be able to rest easy? Are we now to discover that all of that is still not enough? Why does the question hurt so?

Surrendering dearly held beliefs never comes easy but now the chickens are coming home to roost, now we cannot help but acknowledge the possibility that the way we build our boats leaves them inherently vulnerable, inherently susceptible to crippling and potentially fatal wounds. Enough has been said about the various potential Achilles’ heels of cruising yachts, but what if the whole vessel itself turns out to be an Achilles’ heel? As regular readers may have noticed, I take a particular interest in the different approaches to yacht design and construction that have emerged over the years. Anything goes (within reason) for a bit of fun by the coast but sailors with serious cruising on the agenda need to be confident their chosen steed will survive any close encounters of the hungry/expectant/amorous cetacean kind with underwater appendages intact. As always, there will be compromises to be made.

Maybe fish fingers should be mandatory equipment for sailors in future so that there is always something on board with which to placate the orcas should they come knocking? Or should we learn to drive backwards nice and smoothly (as recommended in Spain) to confuse the beasts and send them back to the orca clan for a crash-course in how to overcome their adversary’s cunning new defensive ploy? Or should we just hold our tongue, put the iPhone on mute, stay as still as possible and do everything onboard in stockinged feet? The riddle is as yet unsolved. Solve it we must though: we are still top dog above the water after all and nothing is impossible for us, right?

Maybe fish fingers should be mandatory equipment for sailors in future so that there is always something on board with which to placate the orcas should they come knocking? Or should we learn to drive backwards nice and smoothly (as recommended in Spain) to confuse the beasts and send them back to the orca clan for a crash-course in how to overcome their adversary’s cunning new defensive ploy? Or should we just hold our tongue, put the iPhone on mute, stay as still as possible and do everything onboard in stockinged feet? The riddle is as yet unsolved. Solve it we must though: we are still top dog above the water after all and nothing is impossible for us, right?

However that turns out, it seems we are going to have to revise our ideas about which types of boat are genuinely suitable for use on the open ocean, which represent a safe haven for hopes, dreams, limbs and life and which ultimately come up short. The question needs to be asked, even if doing so lays bare the reality of past errors of judgement. Sailors taking to the water in a boat they now recognise as flawed cannot expect a moment’s peace of mind: sailing as Russian roulette does not make an attractive prospect!

Thanks to the intervention of the orcas, we are starting to realise the error of our own ways. Perhaps the problem lies at least as much (!) with us as it does with them. Perhaps, if we are honest with ourselves in our own decisions, the riddle of their recent behaviour need not trouble us half so much. Perhaps the truth was always out there!

31 October 2021

Peter Foerthmann

EPILOGUE: ODE TO A CREATURE THAT IS SMARTER THAN WE THINK

Hello Peter,

I agree with your analysis about the Orcas behavior with some unlucky sailing boat: It can look sexual . And I would call it in french „l’amour vache“ (kind of harsh love…).

When talking with a Portuguese friend who was on the boat who helped a damaged boat in front of Sines, he told me that the last advice to sailors, after many others, was to stop the boat, if possible, and block the rudder so that it will not move. This was one week after I was told that the solution was to slowly go backwards. And, back in Saint Malo, the solution was to have a metallic tube, with one end in the water and you would knock loudly the other end with a metallic tool. The problem is you definitely have to make a choice, not everything can be done together…

cordialement

Thierry