THE FIVE PILLARS

Two and a half years have whizzed by and it is high time I parked myself in front of the keyboard again to squeeze out another chapter of my life story. This has to be psychoanalysis at its best: it costs nothing and I have to find my own answers on the spot to explain how things came to be the way they were. Two birds with one stone – what could be better? Or am I missing something? Are all these words just setting up a new generation of questions that, like their forebears, will eventually catch up with me and demand a response?

When I first turned (inwards) to this subject in May 2012 I described the content of my life as a harmonious composite of the following:

– Windpilot – to keep the wolf from the door

– Sailing – for fun, adventure and to help oil the wheels of commerce

– Building – I want a roof over my head that keeps the rain out and looks good doing so

– Relationships – everyone has need of friendship and the chance of more

– Cars – the most effective way to link my various pursuits together.

Composure regained – and speaking with the accumulated experience (wisdom doesn’t seem like quite the right word) of my dizzyingly advanced age – I realise that every one of these five spheres of human existence would be more than sufficient on its own to fill (or gamble away) a lifetime. But when one has multiple strong interests, there are open doors (and concealed tiger traps) everywhere, some with irresistible attractions beyond – plenty to keep the curious mind stimulated, in other words. The traps too are crucial to the story: once sufficient time has passed for the deleterious consequences to be digested into the currency of experience, they become a valuable source of knowledge about how to avoid making the same mistakes again (provided, that is, that the circumstances are properly understood and the threads accurately untangled).

As I’m sure at least most of us know very well, however, some mistakes are worth making at least twice; indeed we regularly run head first into the same brick wall over and over with enthusiasm and delight until eventually we make a hole big enough to break on through and move on to the next one.

You don’t have to be a farmer to appreciate the straight furrow because it always keeps you looking forwards. If things go belly up to the extent that you can’t shake off the consequences, the popular refuges, as observed in public life, are a legal/tax advisor, a shrink or the God of your choice. Or you can point the hoary finger of blame at your ancestors, those thoughtless libertines who made the decisions that determined your genetic predispositions long before you were even so much as a twinkle in an eye. It was them, they made me do it, they made me who I am and there’s nothing I can do about it. Or so it is said… To little avail…

If only I hadn’t been quite so naive, he sighs. Regrets. About as much use as that ring on the finger, the one he once held in such awe that he was prepared to overlook being led by the nose, being put on show and making a fool of himself and to croon along with the ballad of eternal love until – here we go again – life enforced a rethink. In many ways 1984 was a stand-out year for all the wrong reasons both personally and professionally as I capered head-long into an ungainly double fault… The error in my private life was comparatively straightforward to iron out, but the memory of my run-in with a former competitor, the manufacturer of the “Swedomat” systems (wild horses couldn’t drag the actual name out of me now) troubled me for much longer. I recount the Swedomat tale here.

This Swedomat debacle was a learning experience for me. At least that’s what I told myself at the time. How could I have known that it would actually turn out to be just the first in a long line of similar disappointments? Plainly the hole in the wall still wasn’t big enough.

BUSINESS

The industrial revolution had yet to reach Windpilot at this time and manufacturing still revolved around the traditional activities of cutting, bending, machining and welding tube and then polishing it diligently with red-raw fingers until the result sparkled brightly enough to catch the sailor’s eye and prise open the sailor’s wallet. The stainless side of things I genuinely enjoyed, but working with fibreglass was another story. I suffered from asthma and allergies in those days – possibly for psychosomatic reasons – and the dust and the penetrating scent of epoxy resin in the air always threatened to set off an attack. I had no option though, because a Windpilot that would work without its rudder had yet to be invented. My role as CEO was a very hands on one too, because we were only busy for at most seven months of the year and subordinates were therefore an unaffordable luxury (if I use the plural here it is only to emphasize that my company and I were a double-act – there was no consistent female support at my side during this phase).

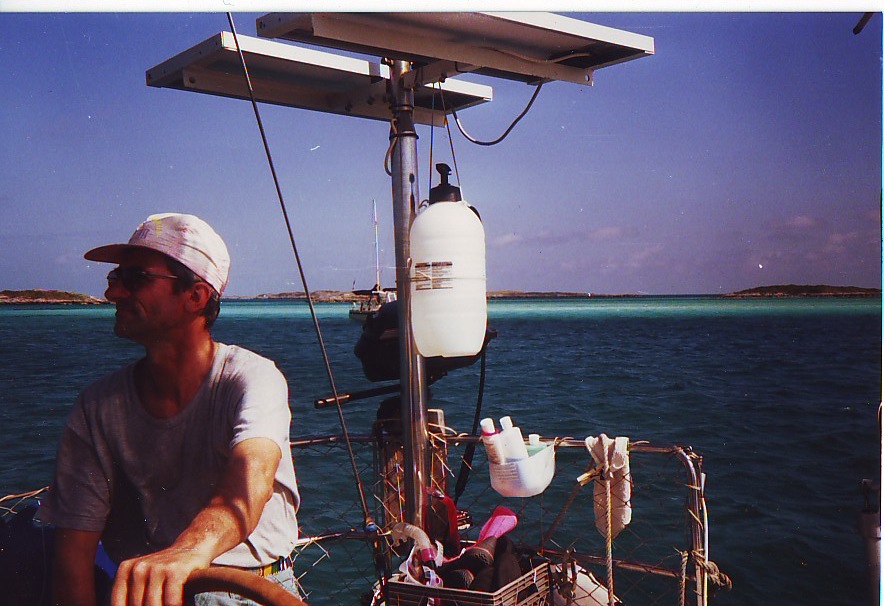

The rest of the year – an enviable five months or so – I used to use for long trips to parts of the world that interested me. I hatched in the course of these travels a perfectly serious plan that still makes me laugh today: when I was older, I said to myself, I would undoubtedly have more time to make the most of this itinerant freedom, ideally with an enchanting female companion to share the pleasures and the highs (and take away some of the angst). Patently a crazy idea I admit, but it had its benefits and helped to keep me always in a positive frame of mind: it’s important to persist in relativising and reframing things in life until such time as you are capable of laughing about them properly, otherwise you risk ending up on crutches (mentally and/or physically) before your time.

TRAVELING, LIVING

I look back fondly on extended visits to Thailand, Malaysia, New Zealand, Australia, the USA and Canada, where I spent many weeks of the year at a time when tourists and sailors were far thinner on the ground.

This was the era in which hippies were learning to love the simple life in beautiful surroundings in Thailand. More than a few decided to stay for good or lost their heart to an almond-eyed angel. My Teutonic sense of duty weathered all temptations, however, and I returned home ready to remount the hamster wheel (or, on occasion, nearly ready to remount the hamster wheel: just a day or two of not straying too far from the toilet to overcome first – and this in an age with no Wi-Fi, no tablet and nothing new to read on the throne but the newspaper).

In New Zealand war ich viel auf dem Wasser unterwegs, habe Peter Kammler auf seiner Farm besucht, die Süd Insel bis in die tiefe Einsamkeit erforscht, bis mir mein Singlehander Leben den Hals verstopft und meine Sehnsucht nach der Heimat – und einer verheissungsvollen neuen Falle in Form einer Dame – mich zum Airport scheuchte. Es wurde wieder Zeit, Europa erwachte aus dem Winterschlaf, männliche Hormone waren mit Wegerecht unterwegs, weshalb ich dann meinen Anrufbeantworter vom Job erlöste und die Anrufe wieder persönlich entgegen genommen, zumal auch anderweitig meine Pflichten erledigen musste.

Travelling so extensively left me with little time for lasting personal relationships; but then a measure of solitude is generally recognised to be very useful when recalibrating life’s compass. I like the “learning by doing” approach in personal as well as professional life: from the slaughter of enthusiastic but ill-advised ventures emerges valuable intelligence about the more obvious pitfalls and how to avoid them (intelligence I don’t always manage to put into practice first time). Physical separation helps to crystallise the mind too: if the combatants once separated have nothing more to say, nothing more needs to be said.

Life’s moments are too precious to squander with the wrong partner. Endless conflict and reconciliation might be more in tune with the spirit of the age, but a clean break with the promise (or at least the possibility) of new opportunities ahead sits much more comfortably with me. Once the head has reached its decision the rest follows automatically – perhaps not for everyone, I concede, but in my case even the most seductive of temptations seem to lose all traction once my mind has resolved to move on. Temptation can do (and regularly does) strange things to reason but with a plane ticket in my pocket and dreams of a distant destination in my head I found that no end of temptation could persuade me to wager any more of my life in the game. And in any case, why prolong the agony?

CHANGING TIMES

A few years of labour in the pattern described had earned the company – and its number one employee – a certain solidity and presence. Over the following decades our foundations became more and more robust and our reputation more and more international until, some years ago now, things reached the point that I no longer had any chance of discretely slipping away for a while. Even when Europe lies slumbering under winter skies it’s peak season somewhere in the world. The Father Christmases of this world have some bulky parcels to deliver these days too as sailors weary of steering warm to the notion of a silent mechanical alternative.

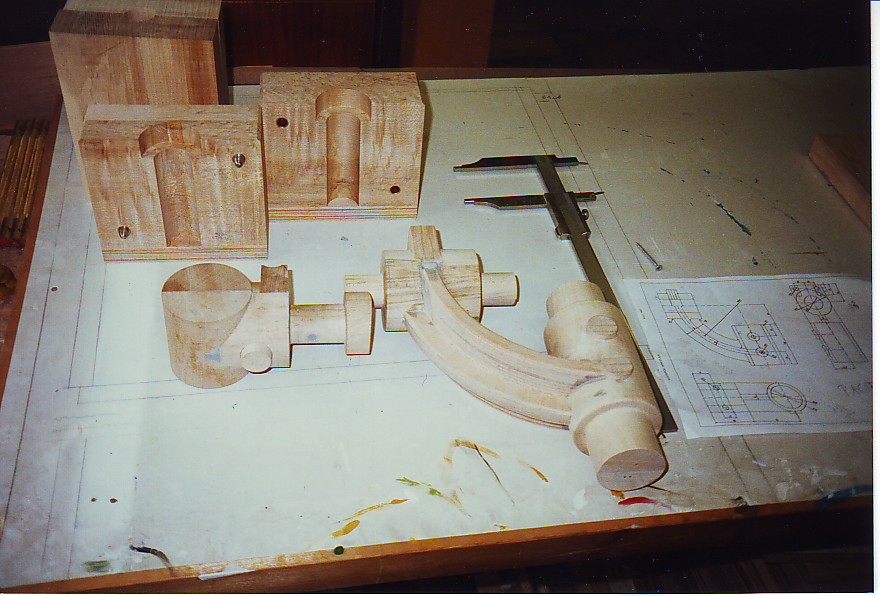

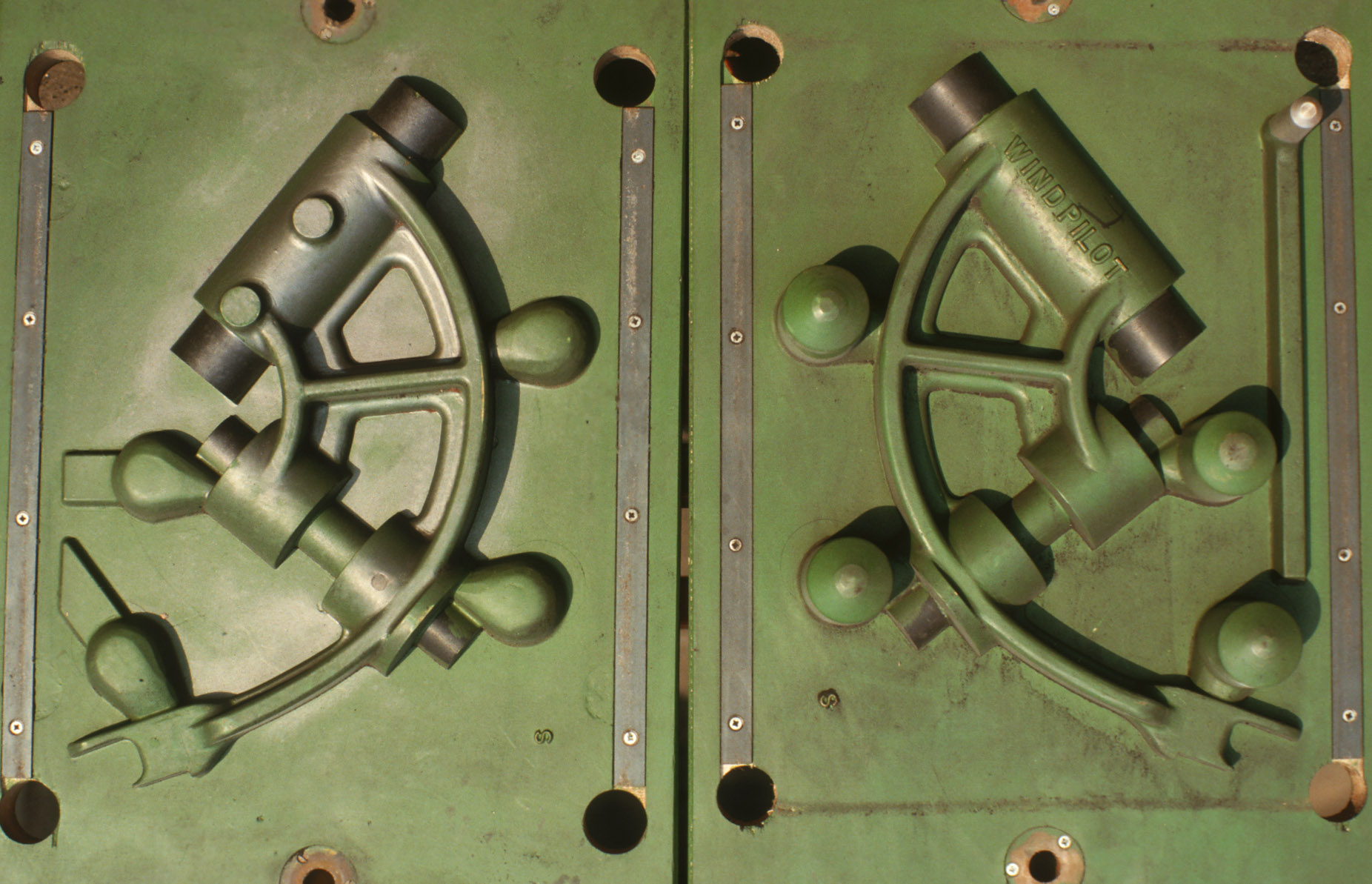

My growing belief in the future of the business led me almost by accident, at some point in the mid-19080s, to the idea that it might be time to stop doing everything by hand and move, in the interests of productivity (or optimising my value added, as I could pay a consultant to tell me today), to sand-cast aluminium. The new production method brought mystery, adventure and plenty of challenges that simultaneously fascinated me, kept me awake for nights on end and put the company’s accumulated financial resources under sustained pressure. Realizing ideas for the new products was a staccato process as thoughts were transferred to paper and then transformed into wooden patterns, the crafting of which was a job for expert patternmakers (who are not to be found on every corner). The artworks in timber resulting from this investment would have graced a gallery, never mind a foundry.

THE BREAKTHROUGH

The decision to create a family of systems based on two closely-related designs, the Pacific and Pacific Plus, turned out to be the big breakthrough, the right idea at the right time. I like to think I have always kept my feet on the ground, more or less, and been aware enough of my own shortcomings not to get carried away with what has been achieved – and I strongly suspect that had the need arisen, I would have had my feet placed firmly back on the ground and my shortcomings carefully enumerated for me in any case. Nevertheless I don’t mind admitting to taking a certain pride in my Windpilot products.

The new Pacifics and Pacific Pluses arrived with us during what proved to be the golden age of the boat show. Sailors flocked to the shows because they were the place to find everything one could possibly want or need for their boat, which also made them the ideal marketplace for the industry. We just about wore our fingers out writing orders at the Dusseldorf show and had to start quoting lead times of six months in order to manage demand.

They were exciting times and I would have needed six hands and 48 hours in a day to bring all of the circulating ideas and projects to fruition at once. There seemed to be a steady flow of new possibilities to consider too such that I was constantly having to decide which were the avenues worth exploring properly and which the blind alleys to be dismissed. Luckily for me all of this happened at the time of the Citroen 2CV, my favourite vehicle for driving and service visits, which had a suspension system with enormous travel – enough to cope comfortably with all of life’s potholes personal and professional.

DEAD ENDS AND PLAGUES OF MOTHS

Windpilot’s star was shining bright and like all bright lights it attracted moths, in our case a plague of human moths who promised to help me with my marketing but who were by and large in it just to help themselves. One employee in Gran Canaria quickly discovered that sales revenues received were best retained in his own account, although he didn’t mind invoicing me for his copious expenses (expenses incurred in many different ways united only in their having not much at all to do with Windpilot). A few months of almost inconceivable tolerance and distress came to end on the main road near Arguinnegan (about as far from Las Palmas as you can be without leaving the island): patience finally exhausted, I slammed on the brakes, invited him to get out quickly and then banished the very memory from my head (until just now).

Another dose of excitement came in the form of a German sailor who, having decided to relocate his life – Hallberg-Rassy and Windpilot included – by sea to La Rochelle, tried to have himself installed as Windpilot’s number one man in France on thoroughly optimistic terms of his own imagining. His generous (just not to me) offer was declined because the chemistry didn’t really work and I feared trouble ahead. Rainer Michelly has since been building windvane steering systems under his own brand. These tend to bear a striking resemblance to a number of other windvane steering systems in production around the world, my own design included. Almost inevitably there was a certain amount of legal wrangling at one point but I have put that out of my mind because being reminded of it makes me angry and I don’t want to make myself angry.

And in 1985 there came a call from Canada. Peter Tietz, originally from Berlin but by this time firmly established in Cambridge, Ontario, was keen to convince me of the benefits of prospecting in the US market from Canada. We visited each other and met significant others and the whole thing seemed very promising indeed. Sales prospects were outstanding and the deal was sealed with a sail on the Great Lakes: Windpilot had feet on the ground in North America too now – it was quite a feeling.

A few initial orders came in from our new outpost but then it all went remarkably quiet until a chance visit from a Canadian sailor at the London Boat Show pulled the wool from my eyes. My visitor, I was informed, was far from happy with “my Atlantik system”. Excuse me, which system? A few questions later I understood that my new (very shortly to be ex-) representative was copying my systems in Canada to market and sell them under my trademark for his own account. Note to self: it may have a great smile, but a shark is a shark is a shark.

Some 15 years later (so strictly speaking outside the scope of this particular part of my bio – but very much related), the same man came back to me full of apologies with a new proposition. Peter Tietz declared himself a reformed character, confessed that he very much regretted what had happened, begged my pardon in the most formal of tones and promised to make it up to me. He then went on to suggest we work together again, this time with him as the representative for my new Pacific systems manufactured using the permanent mould casting process. I was dumb enough to give this man another chance anyway but his wife Susan explained his foolish actions in such a very plausible way that I found myself deeply moved. It was truly remarkable, I thought, that a fellow human could apologise so wholeheartedly for past transgressions. While I didn’t actually set out to portray myself as a complete idiot, unfortunately I have to report that a year later it came to my attention that I had once again fallen for the wolf in sheep’s clothing: Peter Tietz had used my new design as the pattern for his own new copycat design, a system still produced under the Voyager brand. My high-volume surprise visit to his home in the autumn of 1999 and the red faces it produced remain crystal clear in my memory. Experiences like this make us stronger, of course, but there is also no mistaking the warning they convey: envy has a very long reach. The Voyager company was subsequently sold, which tells its own story.

So far (that is to say up to the present day rather than up to 1989) I am aware of seven or so virtual clones of my systems being produced around the world. Imitation is the sincerest form of complement, so this has to be good news: nobody would go to the trouble of plagiarising my contribution to the art in windvane steering if I wasn’t doing at least something right. And with the stories behind these various imposters I have almost enough material for a novel too.

INTERNATIONAL BOAT SHOWS

When Windpilot began marketing actively outside Germany in 1984 it seemed no more than a natural progression. London, Southampton, Paris, La Rochelle, Amsterdam, Oslo, Gothenburg and Stockholm soon became fixtures in the diary – and I soon realised how much I resented both the time events like these consumed and their punitive pricing structures for exhibitors. The inflexible bureaucracy encountered in the UK and also in France caused me particular irritation. Why did the people at London’s Earls Court venue insist that we had to sign in at a caravan tucked away inconspicuously in an out of the way, unsigned and invariably rain-soaked car park before finally being allowed, after hours of waiting, to drive onto the exhibition grounds? There were constant hurdles to overcome on all fronts, most of them incomprehensible to the bemused foreign exhibitor and founded on the most meagre of rationales. Asymmetric warfare was the only option in the face of such overwhelming odds and I brought all of my imagination to bear, quietly driving into the exhibitor’s car park at night to park my car for the whole twelve days of the show without incurring the standard £400 charge, for example, transporting my entire stand (all 700 kg of it) into the hall on a trolley and, at the end of the show, coolly leaving the same trolley by the side of the road in the care of an obliging Bobby while I recovered my car from the car park, loaded up and raced out of London before anyone could realise what I had done.

Friendly local sailors helped the time pass more enjoyably, indeed the friendships forged with people like (Professor of Pathology) Noel Dilly, Tom Cunliffe and others endure to this day, but the conditions for exhibitors really were dreadful. Thank goodness there was always a Guinness to be had down by the pool at day’s end. Completing a boat show application was an obstacle course for foreigners dreamed up with the aid of suspicious English trade unions and I soon realised that having got it right once, the safest course was just to write “same as last year” and spare myself any further misery.

My recollections of the overnight facilities at the damp and wintry Metropole have mellowed with time, perhaps, but I still struggle to come up with anything good to say about the place at any price level. Even being prepared to shell out £300 a night was no guarantee of a clean room with a working shower and in the end I generally hired private apartments, the usual residents of which would stay with friends or family for the duration of my visit and use the proceeds to cover a few months’ rent or repayments. England opened my eyes to a different approach to sanitation too, not least due to the custom of connecting toilets to sewers with pipes that ran down the outside of the building and could consequently freeze solid should winter put in an appearance (which wasn’t such a far-fetched proposition in those latitudes at that time of the year). Mostly though I was so tired at the end of the day that I had no thoughts other than to put my head down until the alarm rang again and it was time to climb back into the ring for another day. Nightlife? Sightseeing? Not a hope! After a twelve-hour boat show day even the most delectable of sensual temptations (should they have been on offer) would have fallen well short of the attractions of an early night.

Possibly even more demanding was the PARIS SALON NAUTIQUE at the Port de Versaille, a massive site located – as the ever-present traffic fumes inside the venue served to remind us – directly beneath the main Paris ring road. Even better, the boat show ran concurrently with two other events: the Salon de Chevaux (equestrian) and the Salon de Piscine (pools and spas). The mingled odours of horse manure and chlorine penetrated every corner of the place, from the toilet cubicles to the crêperie (both a seething mass of humanity at all hours), car parking was available on a pre-payment basis but with the added thrill that paying (through the nose, naturally) did not necessarily guarantee a space, there were two nocturnes, when the doors didn’t close until 10 pm, and exhibitors were required to give a written undertaking that their stand would be staffed at all times (an unhappy situation for solo exhibitors lacking the stamina to do an entire day not just with no lunch, but not even so much as a visit to the toilet). Sometimes after twelve days of boat show it was all I could do to crawl out on all fours.

Boat shows are all about meeting and speaking with customers and – in the case of Paris – breathing their second-hand smoke, watching the ash and, eventually, the butt from their cigarette become one with my carpet while receiving a crash-course in French (conversation can only proceed in French, naturellement), a language that fell by the wayside for me back in my schooldays. On the subject of crashes, the Paris show also meant two weeks of driving practice around the lawless arrondissements every year. Red lights were heeded only as a suggestion (if at all) and even the grinding of metal on metal seemed not to be reason enough to stop: what better opportunity could anyone need to collect scrapes, dents and a persecution complex? There appeared to be no such thing as a parking space that was too small either: if at first the car wouldn’t fit, the driver would just nudge the surrounding vehicles with conviction until voilà, plenty of room. It made sense just to leave the handbrake off seeing as the car would be rearranged in any case. Fraternité had grown thin on the ground on the streets of Paris.

Mon Dieu Monsieur, je ne veux pas allez a Paris encore une fois! Well OK, I exaggerate – but only slightly. You may have noticed that I’ve omitted to mention accommodation in Paris. I can’t face going into the details, but suffice to say, whether hotel or apartment, I like my own toilet and bath (I’d carry them with me if only I could) and I don’t like silverfish, mice or rats (no matter how amusing they might appear on an individual basis). And I like to move under my own steam too rather than being steadily shuffled forwards, always forwards, in the lift or on the metro by the warm, damp crowd. I don’t enjoy crowds. Some people are happy to call someone they’ve never met before who happens to be in their vicinity by their first name thanks to an app, perhaps out of simple curiosity, perhaps out of baser desires or perhaps just because they can – who knows? All of that isn’t for me though. My curiosity has waned over the years in step with my appetite for hearing a changing array of faces tell me the same human stories over and over again.

My adventures and misadventures in Paris cost me two weeks of the year for fourteen years plus plenty of grey hairs, but they didn’t do my business with French sailors any harm; indeed a Windpilot counts almost as standard equipment on the country’s Ovnis, Allures and Boreals. My French customers are even prepared to risk speaking a bit of English these days. Which I bet they could perfectly well have done in the 1980s too, but that would never have done on home turf. The French can make it around the world just fine with a single language provided they stick to French-speaking territories, which, most conveniently, can be found just about anywhere. Unfortunately for us on the other side of the Rhine nobody ever thought to provide German outposts in all the most interesting parts of the world.

Luckily there is more to the French boat show scene than just Paris, most notably the infinitely preferable LE GRAND PAVOIS at the Port des Minimes in La Rochelle. This annual event provides excellent entertainment on and off the water (provided the September weather is kind), lasts only a few days and takes place close to a picturesque harbourside town where snails, oysters and other molluscs top the gastronomic bill and bring endless pleasure to hungry diners (diners with very different tastes in food to my own). Of all the European boat venues, La Rochelle was always my favourite place to stay.

As it happens it was also in La Rochelle that I signed the contracts for my French book TOUT SAVOIR SUR LE PILOTAGE AUTOMATIQUE – a pretty cool experience for a German author on French soil. I didn’t fully appreciate what I was getting into at the time, of course, and had high hopes for a productive relationship. More than two decades and countless requests later, my publisher has yet to send anything my way in terms of liquid reward (cash), royalties or even a copy or two of the publication. The book sold very well – I even bought myself a copy in a French bookshop since I was obviously not going to get one any other way – and has been reprinted a number of times. I hear it is actually not uncommon in France for authors to be “forgotten” once their work is done.

The HISWA Amsterdam boat show never captured my imagination, not least because many of the Dutch people I met there were also regulars at my stand in Dusseldorf. Oslo, Gothenburg, Stockholm – quiet affairs one and all with endless car parks in which the marked parking spaces had even less relevance for drivers – inebriated or otherwise – than Parisian traffic lights. The Scandinavians too seemed to gravitate towards the better known big shows and at that time I tended to see them most often in London.

My North American itinerary regularly took in the ANNAPOLIS, ATLANTIC CITY, MIAMI, FT LAUDERDALE, NEWPORT, CHICAGO, TORONTO and OAKLAND BOAT SHOWS, a nightmare programme that kept me on edge until 9/11, the day that changed New York and the US as a whole and brought my frequent visits to an abrupt halt. I could share endless amusing stories about my experiences at New World boat shows, which in many ways resembled travelling back to the Stone Age. The unconventional approaches employed by event organizers always fascinated me, although even they could never match the brain-scrambling perspectives and circus antics of the footsoldiers of US Customs, whose unfathomable yet insatiable suspicions left me close to losing it altogether on more than a few occasions. They were always particularly curious about the purpose of my visit, as if attending a boat show was a darn strange thing for someone in the marine industry to want to do, and as for the dangerous materials I had with me, surely they were an imminent threat to democracy and the rule of law despite my insistence they were just for steering boats. The waiting was endless and it took a thick skin to deal with it all amicably. It was a role I did not enjoy.

Today everything happens online, which has the enormous advantage that I am spared detention in the boat show prisons of this world, not to mention the eye-watering expenditure that goes with them, and can once again arrange my life and my diary by my own rules. For me at least, the wind went out of the boat show sails many years ago and I do not anticipate adding any more to my running tally of 220 attended. To put things in context, the total number of individual visitors to my stand every year across all of the boat shows worldwide is less than the total number of visitors to my website in a single day.

HANG ON A MOMENT …

I apologise. We are supposed to be in the 1980s here and suddenly I’m wandering off into the joys of online marketing. I sometimes find it hard to stay within one specific time frame, after all it’s such fun to speak knowledgeably with hindsight about things one never even noticed at the time. It’s a kind of rationalisation I suppose – although it might be more productive, rather than glorying in the clarity of one’s hindsight, to think rather more deeply about today’s unknown unknowns.

What other highlights managed to squeeze themselves into the late 1980s?

– In 1987 I made the acquaintance of NANDOR FA in Budapest and gained entry to the VENDÉE GLOBE NON STOP SOLO ROUND THE WORLD RACE non-stop solo round the world race starting and finishing in Les Sables d’Olonne. I fitted Windpilots for Nandor, Patrice Carpentier and José Ugarte, spent many winter nights sleeping in my car among the dunes and took pleasure in the fact that come the end of the race, none of ‘my’ boats had dropped a rig while ‘I’ was on watch despite their rapid rates of acceleration and deceleration and the resulting wild swings in the apparent wind. In fact not only had I managed not to get my fingers burned, but I had even made a few friends into the bargain.

– I bolted my Pacific prototypes to HASKO SCHEIDT´s boat OLAF TRYGVASON in order to keep my side of a deal that went something like: if the Pacific could keep this beast from rounding up, I was cleared to start marketing it to the wider world.

– I mounted the first Pacific off the production line to Ali Peters’ yacht Sasha, where it did sterling service for almost 30 years until a nasty accident in 2014 brought its useful life to an end.

– I fitted the first Pacific Plus to JOSI for INGRID AND JUERGEN MOHNS, who have been roaming the globe with it for decades.

– Oh yes and 1986 was the year JIMMY CORNELL first pitched his tent in Las Palmas. It was inevitable that we should meet there, as I had been accustomed for some time to regard the harbours of the Canaries as my patch, where I would appear bearing (and installing) my special form of transom ornamentation to relieve weary crews of the threat of continuous steering. My story of the ARC can be found here.

After many adventures with boats in need of restoration, renovation, conversion or completion, it seemed to me high time I indulged my second passion in life: years of never having the same roof over my head for more than a short time had left me keen not just for the stability of my own four walls but for the added satisfaction of building them myself. My latent obsession with building first blossomed into a serious disease in the late 1980s. Previously I had only ever squeezed relatively small construction projects into my timetable: a garage or extension here, a couple of bedroom conversions there, a shop crying out for modernisation and, on occasion, something undertaken mainly to demonstrate to a female of particular interest just what artistry in concrete her new liaison was capable of achieving (was ever a woman more classily and convincingly wooed?).

This then marked the beginning of a spell during which my concrete mixer became my second-best friend. New in 1984, this machine served me faithfully for 30 years, blending many hundred tonnes of sand and cement and pouring out whole floors and staircases in a revolving life of churning and regurgitation.

THE PASSION

The concrete mixer took on its first major project in 1988, namely the construction of a smart apartment for its boss who wanted to see his own ideas made real for once and had his bank’s permission to do so. My building madness has bubbled away for decades, sometimes remaining below the surface for ages before bursting forth again in another frenzy of creation. No cure has ever worked completely because some ember always remains smouldering away somewhere in the darkest recesses of my mind until favourable conditions return and the flames take hold properly again. The thirst to express myself in concrete, stone and earth can be indulged but never slaked, it seems.

Designing and building can acquire a momentum of its own that pushes all other considerations aside and I make no bones about admitting my utter powerlessness in the face of this urge. All I know is that it applies only to my own ideas: I could never be reconciled to doing architecture for others because of the constraints and compromises of being thus enslaved. As a piper I prefer to stick to my own tune! Creative thinking works only insofar as one is free to follow one’s own notions and ideas – a life on cloud nine and almost the equal of designing and building windvane steering systems (even whole boats to go with them).

The only permanent physical plans for my first big building project turned out to be just two A2 sheets of hand-sketched drawings. The rest was discussed face-to-face and outlined in chalk on site at six o’clock every morning. This streamlined procedure had all kinds of advantages: no architects (and no artist’s impressions) required, no unnecessary back and forth with this office and that office and complete freedom to evolve ideas and realisation continuously – provided I always had at least the coming day’s work plan clear in my head ready for the morning briefing.

The result made quite an impact on the ladies and gentlemen of the planning department, not least because there was so little paperwork involved. Their tour of the building elicited intrigued but definitely encouraging noises, they noted with raised eyebrows the facts as reported and they were polite enough at the end actually to congratulate me on what we had done as well as signing off on all of the formalities. A day I had dreaded turned into a shock and a pleasure. Even public officials sometimes have their heart in the right place and enough humanity left to appreciate the unconventional – who knew?

Finding skilled craftsmen was thankfully never a problem and I have had the great pleasure of working with the same group of exceptional creators for decades. Father and son team Ernst and Rüdiger Fröhling, gifted master carpenters and one of the cornerstones of our construction and life planning since the outset, have been perhaps the most important over the years and I have enjoyed enormously watching them quietly put their skills into action. My building programmes have no doubt benefited from always being a team effort, with everyone involved in all of the relevant processes right from the outset, and the calibre of individual I have had the good fortune to work with can be discerned from the fact that a handshake has sufficed to agree every project.

So fruitful and rewarding have our collaborations been that I feel inspired to investigate some more. Sadly Ernst died not long ago just a short time into his retirement, but his memory endures not only in the heart but in the many striking examples of his skill that adorn the buildings he helped to create. These monuments speak of a craftsmanship that is all too seldom seen these days as the contemporary obsession with prioritising price over everything else increasingly drives quality into the shadows.

Effectively it became standard procedure for me to erect the basic shell of the building with the usual, trusted specialists and then organise and complete the finishing work myself. This highly efficient approach must have brought tears to the eyes of the people at my bank because it left me needing to borrow much less (and repay much much less) than they would have liked. But that’s their problem…

I digress? Perhaps, but the subject is too important to leave out because it demonstrates the impressive results people can achieve when they work together with mutual respect. One welcome side-effect is that I have also gained a new insight into buildings and modes of living. When dealing with the subject in such a hands-on fashion it does not take long at all to realise that mainstream architecture invests far too little creativity in responding to people’s wishes and needs. People are condemned, by the buildings provided for them, to live in such restricted circumstances and to share their living space to such an extent that they are no longer able to stretch their wings as they might desire.

This brings us up to 1989, but I give you my word there will be another instalment of my public auto-psychoanalysis along soon. The wheels are turning, the memories are flooding back and it has only taken me a few hours at the keyboard to bash out the above – adding spice to the day and cheering me up no end in the process. It has been like having a red-carpet premiere in my own head. And it’s all more or less true too – honest!

Today at least I’m glad to have reached the end of December (albeit it December 1989) and if you have read all the way to here, you must have enjoyed it too, I suppose (I couldn’t bear to think of anyone continuing this far on a purely voluntary basis without taking some pleasure from it). Thank you for sticking with me. Your endurance will be rewarded with another chapter to digest (or avoid, at your discretion), provided I can keep the momentum going.

Just 25 years remain to be addressed. Perhaps we’ll see it right through to the end,

speculates

Peter Foerthmann