STORM, STRESS AND COMPULSON – BUT FIRST A LITTLE BIT MORE SCGOOLING

STORM, STRESS AND COMPULSON – BUT FIRST A LITTLE BIT MORE SCGOOLING

Returning home from the sea with my tail between my legs, my first obligation was to keep a rather lower profile around the adults in my life. While undoubtedly very happy to see her lost son around the house again, my ever-shrewd mother could not help dishing me up a daily reminder of my career mistake and reiterating, complete with gestures of wisdom, that mothers know best. “I always knew a seaman’s life would not sit well with you!” If I heard that pearl once I heard it a thousand times – and there was nothing I could say in retort as I had given her an open goal by coming home.

Life for a time was thus largely a matter of keeping my head down and going with the flow. Resistance was unhelpful, not to say unreasonable.

So I became the very model of politeness and did my best in every way to fit back into my old school class after 18 months of absence. Sweetness and light it was not. The headmistress of my school, Erna Stahl (who it seemed had a soft spot for me) had instructed that I go straight back in with my old classmates, an idea our class teacher found quite unacceptable. She saw me as a problem, a thorn in her side, a provocation in the purest sense of the word: deeply tanned, unruly hair, a full beard – I was nothing short of an outrage to this elderly lady for whom decorum was everything. The beard disappeared, but the affront behind it remained – and continued to rankle.

So I became the very model of politeness and did my best in every way to fit back into my old school class after 18 months of absence. Sweetness and light it was not. The headmistress of my school, Erna Stahl (who it seemed had a soft spot for me) had instructed that I go straight back in with my old classmates, an idea our class teacher found quite unacceptable. She saw me as a problem, a thorn in her side, a provocation in the purest sense of the word: deeply tanned, unruly hair, a full beard – I was nothing short of an outrage to this elderly lady for whom decorum was everything. The beard disappeared, but the affront behind it remained – and continued to rankle.

Come the end of the year I thought I had done enough to move up with the rest of my class, but now the old lady brought her influence to bear to try and compel me to resit. That, I felt, was quite out of the question and all educational levers were duly exploited.

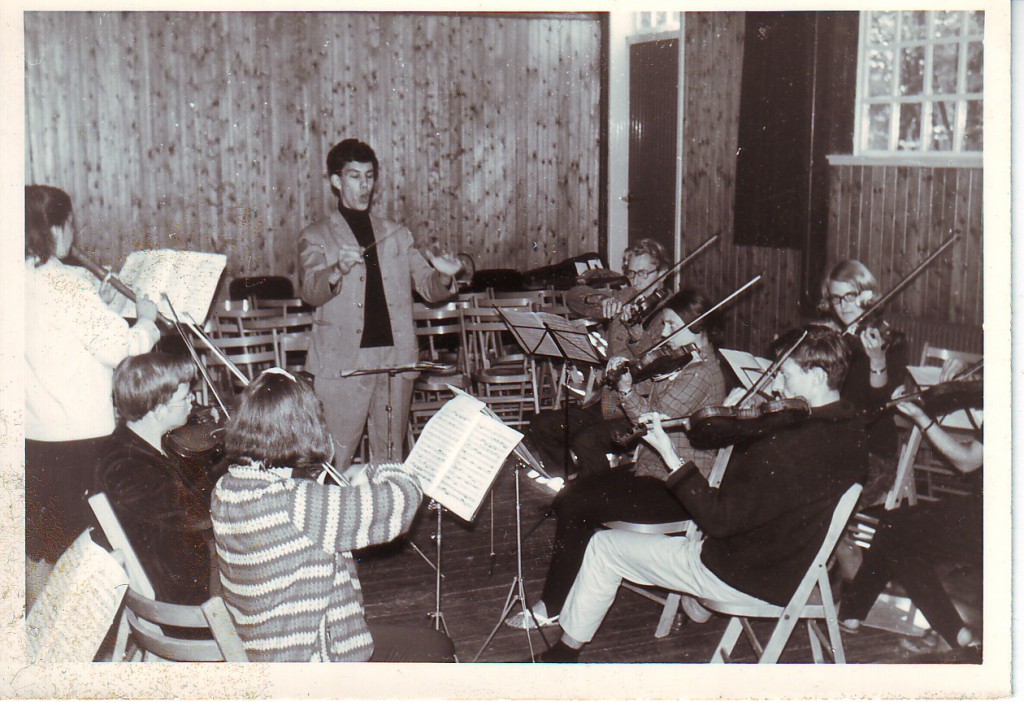

Catching up, I managed to complete my “Abitur”, the school-leavers’ exam required in Germany in order to continue in education, in two and a half years instead of the more usual three. Two factors helped me here: my apparent prowess with the violin and my art teacher’s great enthusiasm for my creative output. Like Steiner schools generally, my school was more than happy to offset particular talents in one area against deficiencies in others, a situation I exploited with virtuoso panache as first violin in the school orchestra (my mother obviously knew what she was doing when it came to choosing a school for me).

With the exams successfully behind me, life was good. The memories of less happy times at sea still remained fresh in my mind too, which only enhanced my enjoyment of the beauty of existence ashore (and of the beauties to be found there).

I never found school especially difficult; my problem was rather finding a way to fit school in around my extra-curricular activities. I, after all, had ground to make up in all areas of my education and not just in front of the books. Today I suppose it would just be put down to delayed adolescence: I spent my acne years at sea with only my thoughts and a bunch of (relatively) old men for company.

THE SCENT OF FREEDOM

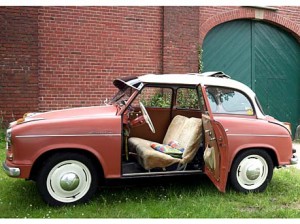

A strange and very useful thing happened to me when I was 18. One summer’s morning I put my portable radio in my pannier and set off on my bike for some time away, only to come home not with the bike but with a car, a Lloyd Alexander TS no less. Really! Along the way I came upon a certain Mr. Seel, who presided over a garage treasury full of old cars. Interpreting my longing looks correctly – if rather generously – he proposed a swap and I agreed and hence I returned from my holiday, bursting with pride, on four rattling wheels not two. I brought a crate of apples with me that I hoped would help placate my ever temperamental mother (I still had much to learn about my mother, the main lesson being to stop underestimating her so comprehensively).

A strange and very useful thing happened to me when I was 18. One summer’s morning I put my portable radio in my pannier and set off on my bike for some time away, only to come home not with the bike but with a car, a Lloyd Alexander TS no less. Really! Along the way I came upon a certain Mr. Seel, who presided over a garage treasury full of old cars. Interpreting my longing looks correctly – if rather generously – he proposed a swap and I agreed and hence I returned from my holiday, bursting with pride, on four rattling wheels not two. I brought a crate of apples with me that I hoped would help placate my ever temperamental mother (I still had much to learn about my mother, the main lesson being to stop underestimating her so comprehensively).

So, in the space of a week, I had mutated into a car-driving student, something I short-sightedly viewed as a privilege. Schools did not provide parking spaces for students in those days, so I had to park alongside my illustrious teachers, who thus earned the dubious honour every so often of having to help me push start my Lloyd, which could be a heavy sleeper in damp weather. The choke demanded a very fine touch: a fraction too much and the engine could be relied on to stop instantly.

Oh foolish youth, what imbecility led me to believe the object of young love’s (and lust’s) desire would be impressed by my new pink automobile? To my sweetheart, the daughter of a strict Catholic family of substantial means, this precariat’s car meant first and foremost embarrassment, an embarrassment she intended to avoid by never, ever, being seen in it by any of our fellow students. Thoroughly understanding of the doors her considerable charms could open, however, she also appreciated that it made for a comfortable – and thus tolerable and acceptable – journey home provided she could board away from prying eyes. Her parents always made me welcome too. They gave me lunch and I was happy to pay for the petrol in the hope of bigger rewards to come. I certainly put in the miles, but progress came much more slowly than I had hoped.

Looking back, the whole experience provided a lesson in the intractability of such families and of the parents in particular, who would never let us out of their sight without a detailed breakdown of why, where and with whom. Their daughter eventually tired of her parents’ intellectual back and forth and took matters in respect of yours truly into her own hands. This, however, proved to be a colossal mistake, the price of which amounted to a swift transfer to what I believe to have been a girls’ Catholic boarding school. Neither of us emerged any wiser from this debacle, but apologies – I digress!

My car, that clattering but ever-willing symbol of my manhood, at the time my pride and joy, triggered scorn, indifference and exclusion. These things strike deep (however justified they might seem with the wisdom of hindsight – bear in mind that, among other peculiarities, this car required driver and passenger alike to reverse into their seat, as the doors were hinged aft), none deeper than the fact that the apple of my eye would only deign to enter in secret under the cover of anonymous backstreets. My moment of triumph lost much for passing unnoticed…

A SETBACK

The next blow came right out of the blue and hit me like a tree trunk: the supreme commander, home front, declined absolutely to give her contrarian 18-year-old know-it-all legal authority to operate a motor vehicle on the grounds that, “The responsibility was too great.” Back then kids remained kids until they turned 21, at which point – and never before – they were considered mature and ready to face the world alone.

A short while later, tail back between my legs, I retraced my route of that fateful summer day to return the car and reclaim my bike. The wipers were going full speed, but it did little good as my tears were falling faster than the rain. I’m sure I needn’t describe how I felt cycling back again to Hamburg and as for the thought of having to wait another three years… Sometimes it is the most trivial events that help to draw the child away from the maternal apron strings – and that provide the richest stimulus for spiritual and emotional development.

Being carless at least took all the complication out of the school run. We went back to travelling by train and bike, gave mother a loving hug and rendered devoted voluntary service around the house – even with the laundry and ironing – in the vague hope of official early access to the car keys and the open road. Situations like these left a young man in no doubt as to the extent of his powerlessness: it’s no fun to live as a child yet see what looks – and feels – like an adult staring back from the mirror every day.

I held this interruption to my motoring against my mother for a long time and immediately began saving, on the quiet, for a DKW Junior de Luxe (with two-stroke engine and automatic lubrication) in which to pull up outside the house at the earliest possible moment on my 21st birthday. Such was my need for car money that I even sold my violin. While this was undoubtedly all part of the process of becoming independent, I came greatly to regret losing the violin (I still do) but by then the die was cast. It is hard to perform physical work with one’s hands and still retain the manual dexterity required to bring the best out of a violin, I told myself – and still do (to what extent this is simple self-deception I honestly don’t know).

But back to the DKW: it had seatbelts, a Blaupunkt radio and, most important of all, reclining seats, an enormous draw for a twenty-something with testosterone to spare, no privacy at home and a reluctance to share any more intimate moments with the unsympathetic wildlife of the woods and fields.

TOTAL FREEDOM

The birthday came and I was off the hook and on the roads for good, or at least until decrepitude, dementia or excessive traffic offences slowed me down again (a day that I hope with all my heart is still a long, long way off).

THE SECOND CAREER

My mother felt most strongly that I should study music or something in the arts, but I, the pragmatist, believed my future lay in entirely the opposite direction. Spurred on by my urge to create wealth and my clear vision for financial independence, I decided to take up a traineeship in export business with the venerable Jos. Hansen & Söhne company, which specialised in trade with Africa from its headquarters in central Hamburg.

The day job, it transpired, left me with time on my hands, so I did nightshifts on the rotary presses at publishers Axel Springer, loaded mail into railway wagons and delivered newspapers in the early hours. I had plenty of time for sleep at my day job: it quickly became apparent that I could easily complete everything expected of me in half a day, so I spent the other half asleep in the packing room.

SIDELINES

I bought up big branded model railway sets all over Germany in the summer months, split them up into smaller units and then sold these, separately packaged, at Christmas. I also dealt in pianos, old baby buggies, televisions – in short anything that could be transported in a trailer behind my DKW. Oh yes, and I used also to make an early morning trip to the wholesale market, bluffing my way past the security guard and into the shelter of the fruit ships berthed alongside, and then distribute bananas and oranges, for an eminently reasonable fee, to the large circle of friends and acquaintances my mother had built up through her interest in homeopathy. I didn’t take long before I started to find the DKW a bit small – and thus began my life as a serial car buyer. The tipping point came when I discovered a 2CV would not only cost little to run and be easy to repair, but could also swallow an entire TV cabinet with the back seats out.

My favourite job, in fact one of my all-around highlights, was accompanying Hamburg one-off and legendary antiques dealer Hans Jessen, whose wife was a close friend of my mother. Mr Jesse had had to spend a considerable time in the USA during the Nazi years and with all the upheaval it had completely slipped his mind to obtain a driving licence (the cost for which would have been minimal). This left him needing a driver for his expeditions across Germany and for a stately 5 Marks an hour I was more than happy to oblige. I found the job ideal: paying a young man to drive seemed to me at the time like paying a cow to eat grass!

We travelled far and wide throughout Germany, my boss buying all manner of beautiful treasures from coins to caskets. Apparently motivated as much by his interest in the objects and their sellers as the business side of the affair, he made time to explain what he was buying and often paid more than the original asking price.

Visiting a town in the rural hinterland one day we came across Farmer Kauz, who had a mighty Baroque cabinet to sell. Mr Jessen’s excitement was plain to see: this was a biggie. The farmer was no fool, however, and his terms – if you want the cabinet, you have to take the old landau in the barn away too – initially left Mr Jessen thoroughly deflated. Then an idea popped into his head and he turned quizzically to me: “Would you perhaps like to have the carriage?” Rather taken aback, I nodded and the carriage was mine! We hired an articulated lorry and found our way back to the farm through ice and snow to collect our goods. We constructed a ramp out of kitchen chairs, trestles and some wide boards, rigged up a couple of purchases using blocks and sheets from my boat and then mobilised the entire farm to bully the three-tonne carriage, complete with fine marquetry, ivory trim, bevelled-edge windows, matching lanterns and even a leather knee protector for the coachman, onto the back of our huge truck. Then we jacked up the back axle, carefully tucked the Baroque treasure underneath and tied as many ropes and straps as we could find around the whole thing before making our way gingerly back to Hamburg. My boss was apparently elated – and I was apparently the owner of a convertible horse-drawn carriage, an object I found it difficult to love at first.

By an amazing coincidence, there appeared in the local newspaper that same winter an appeal from Professor Hävernick of the Museum of Hamburg History: “What ever has happened to the old carriages?” It was almost spooky: had he sensed that I was looking for him? The professor came to visit immediately and could hardly believe what he saw: an unadulterated, undecayed, original old carriage. He literally danced for joy. Then came the proposition: if I would just donate the old thing to the museum and posterity, he would see to it that a proper patron’s plaque was installed in my honour. Vanity (and poverty) not being my thing, I spoiled his mood by requesting cold hard cash instead. The museum paid and the carriage remains on display to this day (without, it has to be said, any mention of its colourful provenance).

THE FIRST MARRIAGE

Unwisely I arrived slightly late for my first wedding, which came in 1969, because I had had to buy a VW Beetle and TV – as far as I was concerned under duress – first. The standard Beetle with cable brakes I found under a pear tree and acquired, after some tough negotiations, for 95 Marks. It took me and, later, my brother all the way to Morocco and must have covered something like 400,000 km.

Unwisely I arrived slightly late for my first wedding, which came in 1969, because I had had to buy a VW Beetle and TV – as far as I was concerned under duress – first. The standard Beetle with cable brakes I found under a pear tree and acquired, after some tough negotiations, for 95 Marks. It took me and, later, my brother all the way to Morocco and must have covered something like 400,000 km.

Anyway, I arrived late and my newly acquired in-laws introduced me to the wedding guests thus: “… and this here is the groom”. Yes, I slipped up, but life writes its own rules and for the man or woman with plans, time’s whip never ceases to crack. My father-in-law sagely observed even before the wedding, “This is not going to turn out well”. Events proved him right of course. It took 13 years, but still there’s no denying he told me so!

Looking back now on my traineeship I’m left primarily with memories of a peaceful time in big smoke-filled shared offices, of two sojourns in Africa, which, not having been raised a master among men, I found rather bewildering, and, finally, of the company’s decision to declare my studies complete and grant me my qualification in export business early on the grounds that I seemed to have picked it all up quite quickly and would be unlikely to learn any more. And with that I was released again to get on with my life. My trainee pay, which came in a brown envelope, amounted to around 100 Marks a month – considerably less than I earned from my sidelines with Springer, the postal service and the other usual suspects. Born into a world far removed from silver spoons and inherited wealth, I considered achieving financial independence to be a major triumph. Life was colourful and exciting and, I had decided, one just had to get out of bed early enough to see the opportunities available and throw one’s hat in the ring and everything else would look after itself.

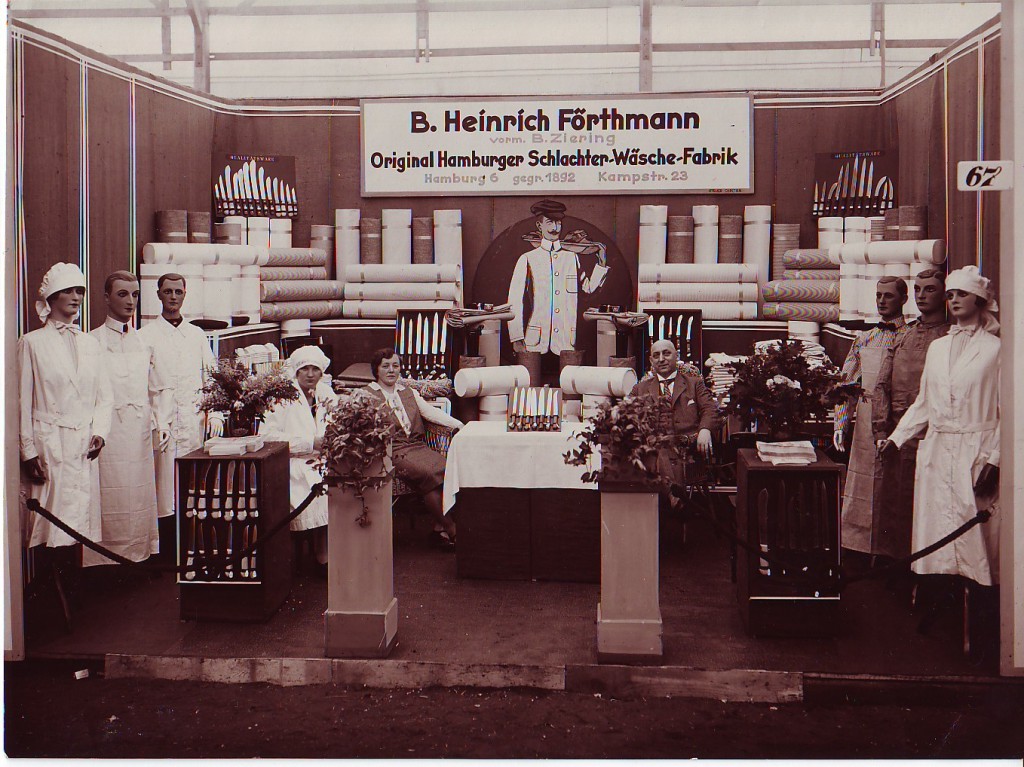

It just so happened that around this time the textiles company established by my grandfather, which specialised in clothing for the meat processing industry, ran into trouble. Following the death of my grandfather, one of the managing directors had assumed control and if not run the operation into the ground, then certainly steered it very close to a lee shore. I decided to jump in on the spur of the moment to take the pressure off my mother.

Abattoir workers are a peculiar people; I got on with them fine, but any women venturing into their realm in those days could expect little in the way of social niceties. These men, their hands dripping with blood, would enthusiastically grab any female who happened to come within reach or let slip any ill-advised comment.

I remember one incident in particular when an abattoir worker came to see us for a cap, as – quite pointlessly – insisted on by the hygiene brigade. His rubber apron covered in blood and his leather bag full of gory cuts received as payment in kind, he plonked straight up to our glass counter, tried on a few different snow-white caps, chose one, paid his one Mark fifty and wandered off again leaving behind blood stains on the two or three caps he had tried and rejected and one big fat splodge of blood on the counter. It was no place for someone with a weak stomach (like my mother), but my grandfather had successfully raised an entire family on the back of the business and my grandmother had domestic and kitchen staff complete with bonnets and white aprons.

My grandfather’s heart disease and sudden death forced my mother to take up the reins, as by this point grandmother could manage no more than eating, TV and crossword puzzles. The business, let there be no doubt, was struggling.

Being taken for a ride is the price millions of people pay time and again for placing their trust in others too readily. The staff certainly knew how to play my mother and I know very well from whom I inherited my own gift for gullibility. A natural healing practitioner first and foremost (or hocus-pocus witch, as my wife liked to put it), my mother was by no means ideal material for managing a business and continued to refer to bank transfers as “write-offs” until shortly before her death. Her special gift and understanding for the imponderables of human existence benefitted her not a jot when it came to settling on and sticking to an effective commercial policy in a manufacturing company with up to 26 confident employees and she consequently had no regrets about handing the business over to me and returning to what she had always found suited her best: when healing human minds and bodies she was in her element.

I was driving my first Porsche convertible at the time, a yellow Type 356A (with the kink in the windscreen) that I had picked up for a song. A cruise to Amsterdam at Easter with the top down – only ENT doctors on a self-help binge do things like that – suddenly turned into a (another) learning experience when the car suffered a flat tire deep into Holland. Struggling to find something solid under which to place the jack, I discovered there was little left of the floor of the car but carpet. We solved the immediate problem by positioning a palette under the engine and jacking from there, but the car clearly had no long-term future and reached its merciful release soon after. The Porsche name already carried considerable weight by that time, but rust has no respect for a man’s dreams – and a car with a life-expectancy of a mere twelve years is surely more the stuff of nightmares.

I sold my grandfather’s company in 1971, by which time clothing for abattoir workers could be had off the shelf and painstakingly stitched uniforms cut to accommodate bellies of varying levels of stateliness were no longer required. The world had moved on and it quickly became obvious to me that supporting between 20 and 26 employees in this line was no longer going to happen. I invested the proceeds in life insurance for my mother, who, for perhaps the first time in my adult life, seemed genuinely impressed with what I had done and was moved to observe that my studies had finally begun to pay off.

I returned to exports for my next career move, selling tools, plant and machinery and D.A.M. angling equipment worldwide for a company in Bremen. The job fell short of my requirements in many areas, primarily because what I really wanted was complete independence. Here, while it is true that I worked on my own in Hamburg, I was still under the direction of head office in Bremen. Being on a lead, even a long lead, did not sit well with me and while the boss seemed happy enough, I knew my future lay elsewhere.

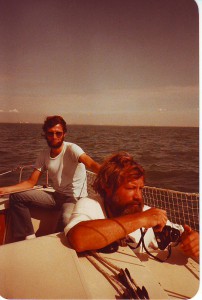

STUDENT LIFE

One thing led to another and almost without trying, I found myself in 1973 signed up to study business administration under the German government’s (then) new programme of grants for students. Thanks to my prior professional experience I enjoyed a student life of relative luxury: happily for me, the grants were based in part on past earnings and I had had a proper job with good pay. Our business administration lecturer Prof. Pegelow, who loved to punctuate his lectures with tales of sailing exploits aboard his Kormoran-class boat, soon recognised me for a fellow sailor and, when the opportunity presented itself, asked me enthusiastically what I was sailing myself just then. As it happened, I already had a rather nice yawl and I made the mistake of admitting as much. Somehow afterwards I could never rid myself of the sense that someone like me sailing a boat like that just did not fit into this man’s view of the world. My marks in his subjects certainly never entirely recovered.

Student life was a wonderful time, mostly because we, my dog Max and I, had plenty of time. Max Förthmann was a rascal and my constant companion. He guarded my car while I sat in lectures (except in winter when he came inside in the warm, usually, but not always, keeping his mouth shut) and quickly made himself well known around the university. The old adage about dogs looking like their owners (or vice-versa) had more than a grain of truth in it in our case: we were both shaggy-haired and unkempt, for example, and usually had no reservations about letting our views be known. The mutt, however, also had no reservations about venturing off into town on extended nocturnal expeditions, returning home, visibly exhausted, to drag himself onto the sofa and sleep the day away, whereas I managed to maintain at least a veneer of civilisation and generally did not demand exclusive use of the furniture. Life, in short, continued in its usual turbulent vein!

Max later became the child of a broken home, having to go and spend time with my ex and my successor in the very house we had once called home. The new man about the house once had the ill-conceived idea of turfing Max out of his established lair in the bedroom. This forced relocation to the cold tiled floor came as a grave affront to a dog accustomed to long-standing privileges and he wasted no time in making his feelings clear. Banished behind the kitchen door to muffle the sound of his nightly protests, he deposited a generous offering on the cold tiles right in the doorway. When the door swung open for the usual morning greeting, his night’s work was instantly spread out into a none-to-shallow slick whose fiendish slipperiness claimed both the lady of the house and her new friend (this is the truth as I understand it). The ploy worked and Max reclaimed what he saw as his rightful place at the end of the bed, from where he presumably went on to ponder (perhaps not for the first time) the great unpredictability of life as a dog.

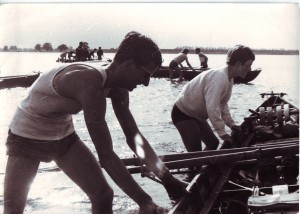

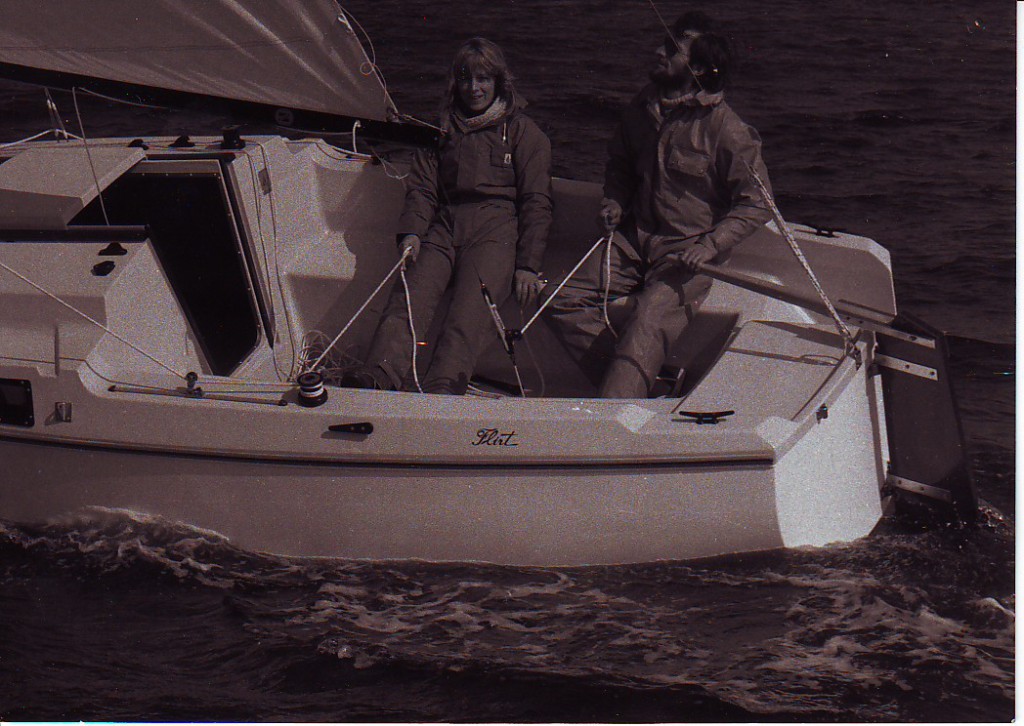

Student life left me plenty of time for sailing and other adventures but before long I was working again, doing jobs for Fisher yachts importer Peter Deichgräber. The arrangement began quite by chance when Peter noticed me step both masts on my yawl Lilofee single-handed. He offered me a fair deal and I was happy to accept it right there and then. I also raced regularly with yachting author and journalist Peter Schweer and worked with him on a number of tests for German magazine YACHT in La Rochelle.

Happy is the man who is able to make a career of his hobby. I was fortunate enough to have – and seize – this opportunity at a young age. True freedom, I would suggest, begins with the ability to dispose of one’s time as one wishes and while self-employment has not been without its downsides, I have found them a small price to pay and have as yet no complaints!

There comes a time in life when decisions have to be made and nettles grasped. Some attribute such moments to fate, but I prefer to think of them as a fair and just reward for always being prepared to welcome new adventures and challenges with open arms.

The new adventure that would turn my life upside down first sniffed me out on the very day I put my steel yawl up for sale. Yes, I still have more to tell,

promises

Peter Foerthmann

Hi, Peter, durch Silke auf deine Tätigkeit aufmerksam gemacht, las ich deine Seite mit Interesse und auch Schmunzeln! Du hast ja Tolles aus deinem Leben gemacht. Zu bewundern! Dass ich auch die Ehre habe in deinem Blog sogar bildlich zu erscheinen, macht mich richtig stolz! Nur um bei der Wahrheit zu bleiben:meine Eltern waren niemals katholisch, nur einfach sehr prüde. Und zum Glück habe ich auch nie die Schule wechseln müssen! Das rosa Auto kam mir wieder in Erinnerung und ich weiß noch wie peinlich ich es damal wirklich fand!

Wünsche dir weiterhin alles Gute und viel Erfolg im Leben.Liebe Grüße von Ilka