PUTTING THE PIECES TOGETHER

It was Wednesday the 2nd of August, 2017, and I was driving towards Hamburg airport when I heard on the radio that the Peking had returned. The steering wheel turned as if by itself and before I knew it I was on the runway to Wischhafen on the lower Elbe river to pay the famous old vessel a visit.

The four-masted barque Peking made the crossing from New York to its new home on the Elbe aboard a semi-submersible heavy-lift ship before being towed to the Peters yard in Wischhafen, where it will be restored and displayed as a part of Hamburg’s maritime history. And the yard certainly has plenty on its plate with this job: the sight that greeted me was more hulk awaiting the cutting torches than awe-inspiring queen of the seas.

A few painted “runes” on the side of the hull warned dock workers to “please, please” avoid applying any force to the areas marked, presumably because the paint was the only thing still holding it all together. Seeing the Peking again was like coming face-to-face with my past, with a web of ancient stories; stories that affected the course of my life in ways that I only properly came to understand with the benefit of several decades’ hindsight; stories that are quite literally a part of who I am. It has taken some time, but after much puzzling and contemplation I think I now understand why the return of the Peking touched me so profoundly.

THE FLYING P – LINERS

I have been fascinated by the giants of the Flying P Line, as Hamburg’s Laeisz shipping company came to be known, ever since I first started taking my bike and portable radio down to Hamburg docks to see the ships at the stately age of six. Publishers like Brigantine and Köhler had book after book on windjammers in print in those days, every page bursting with information about the tough life aboard and the derring-do of the splendid characters who used to captain these unmotorised square riggers.

I lapped up the stories of Felix Graf von Luckner, the “Sea Devil”, like all young boys in my part of the world and filled in the gaps for myself by keeping my eyes and ears open down at the docks. Here were true Cape Horners, men of the sea who regularly battled their way through the wildest seas on Earth with only canvas to keep them moving.

Quite overcome, I sometimes found myself staring open-mouthed before these astonishing wind-driven machines for hours. It was difficult for a young boy and his bike to make it home on time when there were such scenes to behold, but my mother’s wrath was always limited by her understanding for my enthusiasm. Ultimately, she had the wisdom and insight to trust me and allow me to live a slice of my life as an independent person even at that young age. Being trusted like this, I believe, helps children to develop the sense of responsibility they need for later life as well as helping the parent-child relationship endure as the years pass. It’s all just common sense, I’m tempted to add, but looking around at the world outside it is clear not everyone would agree.

TRAGEDY IN JULY

A single story dominated the newspaper headlines in Germany on 23 July 1958: the loss of the four-masted barque Pamir in Hurricane Carrie. The shaky pictures on the TV brought more of the same and unusually for our house we were allowed to watch even in the afternoon. This would have been out of the question in normal circumstances: the evil box of flickering light usually skulked under a woollen cover until evening at my mother’s insistence (on the grounds that TV was unseemly for an upstanding, musical family like ours), only to be brought out once there was no danger of being caught in the act of viewing (and then watched intently with ever squarer eyes until the end of transmission). The loss of the Pamir was the topic of the day around the kitchen table – and not just because the son of close friends, the Gutschow family, had had the good fortune not to sail with the ship as originally planned.

I never fully grasped back then why the sinking of the Pamir was always on everyone’s lips in our house. There were good reasons, but I could not have known what linked us to the ship at the time. I was briefly gripped and shaken by the event, but had so much going on – still had so much to discover along the waterfront – that I was never going to muster much interest in how the details related to me and my family on a personal level. I was a busy Hamburg kid whose days were always too short thanks to a two-hour round trip for school, endless violin practice, boys’ choir rehearsals at the church and my many maritime interests to pursue plus all kinds of books to keep me awake at night reading under the covers by torchlight (at least until my mother confiscated the torch, after which all that remained were the crackly lo-fi headphones for my radio and the Bach, Beethoven and co. with which they lulled me to sleep). I could have done with two of me, just to help fit everything in every day.

Thinking back, I suspect it was around this time that the idea of going to sea myself – on one of the Laiesz company’s flying P-liners of course – first took root in my mind. When the day came, however, I shipped out not on a four-masted barque but on a banana boat with not a sail to be seen. It was 1964, I had recently turned 16 and we (me and the MS Pisang) were off to serve what was scheduled to be a seven year tour on charter in the Pacific. Thankfully events dictated otherwise: the Japanese charterer went bankrupt after 18 months, cancelling the charter, and we were ordered to Rotterdam, which enabled me, to my great relief, to take early retirement from the shipping industry and move on to the next thing. It was certainly a learning experience, therefore valuable in its way, but I quickly realised I really didn’t enjoy being isolated at sea in all-male company – and I still don’t!

THE CALL OF THE GENES

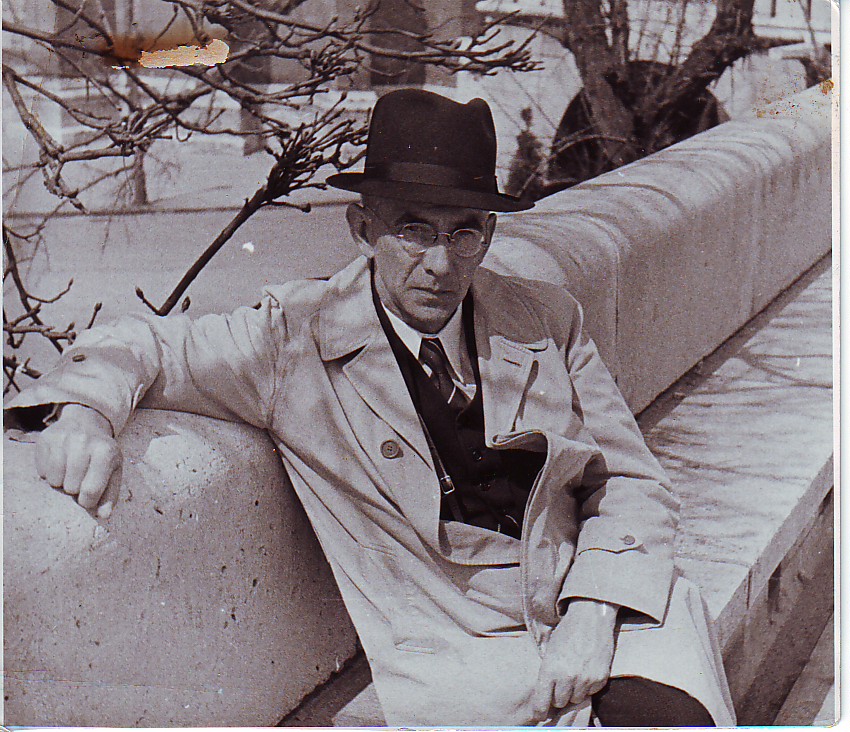

Born out of wedlock as the son of a man well-known in seafaring circles, I was able to glean only fragmentary information from my mother about my father, who played no active part in my life (which was not then and has never been an issue for me, as it happens). I knew his name though (Dr. Otto Hebecker, born 04.11.1888, died 28.3.1977) and was aware that he had made a significant impact in quite a range of settings including the Hamburg maritime college in Övelgönne, the Hamburg Ship Model Basin (HSVA), Meyer’s yard in Papenburg and the spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana (and not just in matters maritime and aviation).

The course of my father’s life made the perfect alibi for a flighty dreamer eagerly trying to pin down, sort, define and somehow articulate his genes and desires. Later on I did of course have the chance to meet my father in person: I was 21 and already married, my father was 80, freshly arrived from Guiana, crackling with energy and apparently just as curious as me.

SPEAKING OF CURIOSITY

Curiosity is an integral part of being a boy, just like “NO”, “I’m not eating it”, “I don’t want to” and “I want to do what I want to do (but I’m not sure what that is)”. Situation normal, in other words: then as now, life for young people revolved around finding the action. Provided, that is, they weren’t afflicted with overly controlling parents dead set on indoctrinating (terrifying) them out of making their own life experiences. I certainly did my share of blubbering when those experiences out in the wild went wrong, but still I could never have countenanced a life as know-it-all sheltering in mother’s cosy doll’s house until adulthood (not that we had a doll’s house on offer anyway – our home was a colour-coordinated place of order dominated by piano and harpsichord and, on the occasions when my mother freed it from its woollen cover, the TV).

I was a committed awkward so-and-so who liked nothing better than to follow his nose wherever it took him (a nose whose length he found uncomfortable in the company of girls). Also something of a lone wolf, I found I seemed to be able to absorb knowledge and experience in all kinds of areas and subjects quickly and this brought me a measure of confidence: being skilled in multiple disciplines, I realised, gave me a competitive edge that would come in very useful when chasing skirts. Failing that, it was at least better than being an idiot… Being good at learning things for myself also allowed me to set my own pace, which saved me time I was only too happy to dedicate to other pursuits.

LIFE THE WAY I WANTED IT

I filled the 20-year wait for the first meeting with my father very well, in other words, assembling (inventing) my own explanations for things as a youngster and then later on sorting and organising my understanding of myself and my origins over time until the world I had built around me and my place within it felt secure, felt like mine and felt Goldilocksishly just right. And there (and here) I complacently sit to this day. I never noticed anything missing, any void or trauma due to my father’s absence. My mother put in a bravura performance in both roles and I loved her for it every day of her life.

I guard the abilities I came into the world with like an inexhaustible treasure. Sometimes they simplify my dealings with other people enormously, but my tendency to be too trusting of the words of others has also dished me up some miserable setbacks. Did people not warn me enough of the depths to which some people would be prepared to sink? If you bang your head against the wall hard enough and often enough, either the message eventually makes it through to the brain or the hole in the wall grows large enough that you can squeeze through and carry on going. This pearl of hard-earned wisdom I offer you for free!

Weave all of these different strands together and you have ideal conditions for a young man’s imagination to turn an absent father into a larger-than-life figure and idol. The less real information I had, the more scope I enjoyed to let my fantasies run wild. I am quite sure, from the perspective of today, that it was these years that spawned my urgent yearning to shake off the shackles of comfortable bourgeois existence. My life’s heroine – my mother – acknowledged as much with a knowing smile and left me free to get on with it, which only enhanced my great admiration and respect for her (especially as it put an end once and for all to her dream of having a virtuoso violinist for a son). Ultimately though we each have to find our own priorities for life – albeit we may well start the process with no idea where they lie. A game of Russian roulette with me as the bullet…

PANDORA´S BOX

When a former school friend with an intimate knowledge of the Hamburg city archives (Dr. Angela Graf) mentioned to me, decades later, that my father’s activities figured repeatedly in the records, I decided the time had come to open Pandora’s box and plunge in (this was still in the days before Aunty Google ruled the roost).

I was now more curious than ever about my father, as by this stage I had read the extensive diaries left to me by my mother when she died. Reading my mother’s diaries touched me deeply: suddenly I was able to tie up all kinds of loose ends that had previously been floating around in my head with no obvious logical connection. Sitting at her Continental typewriter, my mother had meticulously transformed the familial puzzle (on the thinnest copy paper imaginable) into a captivating family history in which I, naturally, had a prominent role. Now I was learning the whole story, an extraordinary process that told me more about who I was and supplied explanations and pointers that I would never have stumbled across any other way. If only there were some way to turn back the clock a little! The cornerstones of my mother’s life have now become the cornerstones of my own as I discover ever more ways in which my identity mirrors hers.

THE PAMIR ENQUIRY

I now know that my father, one of the experts called to testify during the official enquiry into the loss of the Pamir, contradicted the theories of other experts involved by explaining in meticulous detail how the vessel must actually have sunk some 25 nautical miles away from the previously accepted location. The rescue effort had therefore been concentrated in the wrong place, which explained why it had retrieved so little. He had also drawn on his knowledge of vessel stability matters (he was an acknowledged expert who understood sailing and motorised ships and had several patents to his name) to assert that, for a number of reasons, the Pamir was doomed to end up on the sea floor in any case. These views naturally proved highly controversial at a time when the whole nation was caught up in the human aspect of the tragedy and the loss of such a large number of young cadets.

The loss of the Pamir signalled the end of an era in German seafaring as cargo-carrying sail-training ships disappeared. The Passat was soon decommissioned and has been a landmark and youth hostel on the waterfront in Travemünde for many years. I came across the Passat’s sister ship Peking in New York many years ago in a rather unglamorous part of the New York waterfront and visited her around the turn of the century, by when she was already in a very sorry state. The resurrected Peking will be a very welcome reminder of my own origins.

NO BLAMESTORMING HERE

Let me make it perfectly clear – lest anything I have written should create a false impression – that I am not joining the ever-expanding herd who dream up and deliver generalised reproaches to their parents as a consequence of and excuse for their own dissatisfaction with life and a way to deflect attention (chiefly their own) from inadequacies closer to home. Why does it seem to be so en vogue today for people to blame their forebears for their own failure to find purpose and direction in life? Behaviour and interactions within and between families now often appear to be dominated by fusillades of accusations and staggering expressions of envy that almost always stem from nothing more concrete than individuals’ own discontent.

These fusillades are leaving whole generations of parents battered and undermined, with many lacking the strength to go on defending themselves and falling instead into acceptance of a fate they could once never have imagined possible. The battle within and between the generations is able to rage with such unrelenting ferocity because sharp elbows and me-me-me are apparently the default setting for many people today (and while words like sympathy, understanding and compassion still feature large in the general vocabulary, the meaning seems to have been hollowed out of them). Sad as these developments are to witness, they represent a trend even the best efforts of bluewater sailors and silent self-steering manufacturers cannot hope to reverse!

I have always considered myself one of the lucky ones, a born optimist curious about the world and determined to go out and explore it. A boy like me would no doubt find himself a prime candidate for Ritalin “treatment” in some homes today. What a sad thought! I used to launch excitedly out of my bunk every morning and charge headlong into whatever minor catastrophe the day had in store for me (as I have enjoyed recording here in my blog as semi-serious self-psychoanalysis and to set my soul in order in case of unexpected peril on the sea). This has enabled me to maintain my cheerful outlook and accept the various misadventures in which I have become entwined as just another stitch in life’s rich tapestry, which has proven to be a useful trick and one without which my many misadventures might have been much more difficult to survive. But survive them I have – and I couldn’t be happier about it.

I believe I have my mother to thank for my predisposition for music, colour and design, my affectionate and sympathetic nature, my humorous outlook and boundless love of a joke and my steadfast morality in interpersonal relationships. Oh yes – and for my infatuation with writing!

My father, it seems, deserves the credit for my affinity for engineering, my irrepressible urge to find the logical connections behind affairs and events and my capacity to stand my ground. I hope he has also passed down to me his longevity and the resilience that enabled him to go on making the most of his abilities until the end.

I am grateful to be the happy result of the meeting of two such admirable people and to continue adding pages to the story they started.

Too much information? My apologies, but it would have been worse to say nothing at all!

Peter Foerthmann