Gone are the days when carefree sailors drew together in the autumn in Las Palmas to make new friends, pay a consideration to Jimmy and allow themselves to be swept up in his idea of an Atlantic Rally, a fun regatta in which the rules – delivered with a knowing wink – were few and the possibilities manifold. Taking part was everything.

Gone are the days when carefree sailors drew together in the autumn in Las Palmas to make new friends, pay a consideration to Jimmy and allow themselves to be swept up in his idea of an Atlantic Rally, a fun regatta in which the rules – delivered with a knowing wink – were few and the possibilities manifold. Taking part was everything.

There were plenty of 30 footers and family crews were the rule rather than the exception. The total number of participants was still small enough that when the time came, every single one of them could squeeze into the flapping marquee on the dusty unpaved harbourside to take their final instructions out of the blaze of the fierce Canaries sun. The assembled vessels were modest, their owners likewise. Sextants were still in evidence, the atmosphere was friendly and open and the ‘social programme’ developed spontaneously as crews met and mingled.

When I first started travelling down in 1979, I saw the Canaries as the perfect place to prepare for winter in Northern Europe with a last dose of sunshine while waylaying resting westbound sailors to share a few words of advice in matters of steering relief. Virtually every route taken by sailing boats bound for the New World passes through the Canaries, so there are a very few places in the world where someone like me, then a relatively new, albeit already completely absorbed, figure in the world of self-steering could harvest so much feedback in such a short space of time. And harvest it I did – by the bucket-load.

When I first started travelling down in 1979, I saw the Canaries as the perfect place to prepare for winter in Northern Europe with a last dose of sunshine while waylaying resting westbound sailors to share a few words of advice in matters of steering relief. Virtually every route taken by sailing boats bound for the New World passes through the Canaries, so there are a very few places in the world where someone like me, then a relatively new, albeit already completely absorbed, figure in the world of self-steering could harvest so much feedback in such a short space of time. And harvest it I did – by the bucket-load.

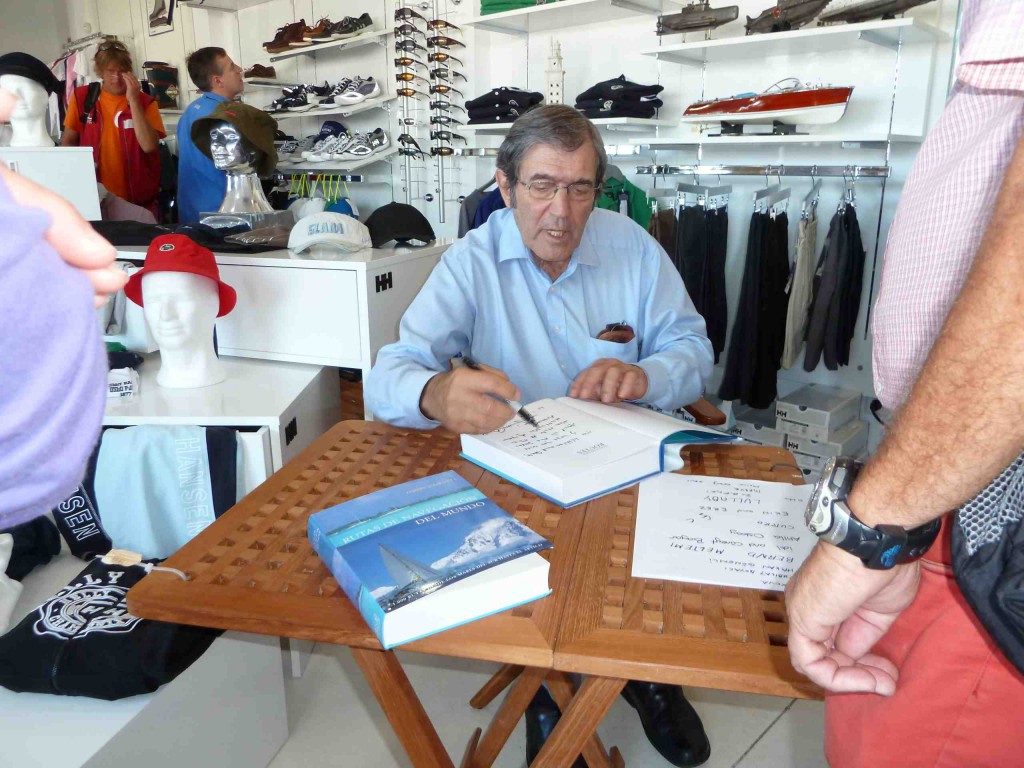

It was while prowling the harbour in 1986 that I met Jimmy Cornell, who had pitched camp with Gwenda in Las Palmas for the first time that year. Keeping my distance at first, I carried on scurrying from boat to boat preaching my mantra, calming nerves, reassuring anxious partners, giving windvane steering systems of all makes and models a little pampering and, of course, enjoying happy times in the sun with good people. A non-profit approach seemed logical. Waving invoices around would be a sure way to spoil the mood and in any case it was undeniably a two-way street: the more I shared my experience, the more I learned myself.

It was while prowling the harbour in 1986 that I met Jimmy Cornell, who had pitched camp with Gwenda in Las Palmas for the first time that year. Keeping my distance at first, I carried on scurrying from boat to boat preaching my mantra, calming nerves, reassuring anxious partners, giving windvane steering systems of all makes and models a little pampering and, of course, enjoying happy times in the sun with good people. A non-profit approach seemed logical. Waving invoices around would be a sure way to spoil the mood and in any case it was undeniably a two-way street: the more I shared my experience, the more I learned myself.

The years passed and Jimmy’s fleet grew into a veritable armada. Acquaintances were made and friendly greetings exchanged. “Same procedure as every year”: that’s how it was and that’s how everyone seemed to like it. The ARC team was a merry band in those days, with much of the work done on a voluntary basis. One day, some seven years on from our first meeting, Jimmy appeared in front of me, jabbed a finger at my stomach and commanded me to the Club Nautico that evening: “Eight o’clock sharp”! I was terrified. Not only that, but I hadn’t a single pair of long trousers – then as now a non-negotiable ingredient of the dress code for this esteemed island gentlemen’s institution – in my bag. Deciding not to go was the easy part; facing the music the following morning was much, much more uncomfortable. It transpired Jimmy had wanted to present me with an award in recognition of my service to the ARC. Luckily for me, I had the award pressed into my hand on the dock the next day despite my no-show and I confess it hangs on my office wall to this day.

Jimmy and I eventually became good friends despite this inauspicious start. We organised seminars in Las Palmas, London and the US, launched a German chapter of World Cruising together with Astrid and Wilhelm Greiff and established bluewater seminars as a regular component of the Hamburg international boat show in 1998. We found a welcoming audience and fun was never in short supply.

Jimmy and I eventually became good friends despite this inauspicious start. We organised seminars in Las Palmas, London and the US, launched a German chapter of World Cruising together with Astrid and Wilhelm Greiff and established bluewater seminars as a regular component of the Hamburg international boat show in 1998. We found a welcoming audience and fun was never in short supply.

Jimmy’s decision to sell World Cruising at the end of the millennium marked the end of an era. It was entirely understandable and had little direct impact at the time. Apart from conferring the title of Managing Director on Jimmy’s former assistants, new owner the Challenge Business initially changed almost nothing. The team still roamed the harbour in conspicuous yellow T-shirts, but the wind was shifting and Jimmy’s absence cast a long shadow.

With Chay Blyth came new directives: this was serious business and commercial imperatives came to the fore. The transformation of a bumpy corner of the harbour into a proper marina with its own breakwater began on Jimmy’s watch, but the upgrades that now commenced shoreside came more in the style of the new regime: dirt tracks were surfaced, shopfronts sprouted from former car parks and restricted areas were established and thereafter patrolled (for a fee) by the Policia Local, Guardia Civil and Policia Portuaria.

With Chay Blyth came new directives: this was serious business and commercial imperatives came to the fore. The transformation of a bumpy corner of the harbour into a proper marina with its own breakwater began on Jimmy’s watch, but the upgrades that now commenced shoreside came more in the style of the new regime: dirt tracks were surfaced, shopfronts sprouted from former car parks and restricted areas were established and thereafter patrolled (for a fee) by the Policia Local, Guardia Civil and Policia Portuaria.

A further change of ownership (was the business just not interesting/profitable enough?) in 2006, with Andrew Bishop, Jeremy Wyatt and Adam Gosling acquiring World Cruising Ltd. from Chay Blyth and transferring operations to Cowes, Isle of Wight, which remains their base, stirred the mix again. A network of event, port, corporate and supporting sponsors, the latter group more than 20 strong, altered procedures, atmosphere and customs in Las Palmas over subsequent years. It immediately became necessary to pay several thousand euros to the organisers simply for the right to offer help to their customers gathered in the marina. The tight links between organiser, sponsor companies and local authorities have since become a significant barrier to service providers. Any that omits to cross the organiser’s palm with silver in advance faces being removed from the harbour, in some cases by the police no less. One German engineer actually ended up spending a night behind bars.

In just a few years the service and equipment companies on site have built an effective monopoly. There is almost no limit to what can be bought by the waterside in Las Palmas now, but welcome as that may be, there is seemingly no limit to the prices that can be charged either. Service providers from other ports around the island have found it impossible to compete on these terms, leaving a monoculture offering little in the way of options for the sailor on a budget.

In just a few years the service and equipment companies on site have built an effective monopoly. There is almost no limit to what can be bought by the waterside in Las Palmas now, but welcome as that may be, there is seemingly no limit to the prices that can be charged either. Service providers from other ports around the island have found it impossible to compete on these terms, leaving a monoculture offering little in the way of options for the sailor on a budget.

Yachtsmen and women with relevant skills used to be able to boost the ship’s kitty during their stay in the Canaries by arranging to have their services promoted through local companies – the port operators – to other yachts. Nautical folk saw this as par for the course: word spreads quickly in harbour and good people are always in demand. Now these skilled craftspeople have moved on, most of them to points West.

Sailors wishing to augment their budget in the current climate have to do so on the quiet and, quite possibly, away from the water, as anyone who takes the trouble to enquire openly about opportunities faces being expelled from the harbour. I recently visited one sailor riding at anchor in Las Palmas whose cockpit was brimful of wood shavings – hardly the best workshop for a carpenter looking to turn his handiwork into cash. Another brother of the sea was actually expelled from Las Palmas after being caught looking for work.

Sailors wishing to augment their budget in the current climate have to do so on the quiet and, quite possibly, away from the water, as anyone who takes the trouble to enquire openly about opportunities faces being expelled from the harbour. I recently visited one sailor riding at anchor in Las Palmas whose cockpit was brimful of wood shavings – hardly the best workshop for a carpenter looking to turn his handiwork into cash. Another brother of the sea was actually expelled from Las Palmas after being caught looking for work.

Today the providers in situ keep an eye on “law and order” in conjunction with the ARC organisers. While this certainly protects their own margins, it does little if anything to help sailors to a better or cheaper solution for their problems. The ARC has thus become a world unto itself in which the official event sponsors are able and encouraged to go about their business without fear of competition under the auspices of the organiser and the authorities. Las Palmas in November is no longer the best place to be for non-ARC sailors. Even long-term guests are directed away from the harbour in short order if they have not been cunning enough to find a space in the Club Varadero, which while better value than the marina next door has but a few visitors’ berths.

The ripple effect of the ARC’s rigid berth occupation policy has spread to other ports on the island and, indeed, to ports on the neighbouring islands. Apparently some crews have even signed up for the ARC on the spot simply in order to avoid having to surrender their berth. The shortage of accommodation at this time is only exacerbated by the locals’ love of powerboats small and large, every one of which needs a berth. Hundreds and hundreds of oversize motorised bath toys sit bobbing in Puerto Rico, Pasito Blanco and Las Palmas, covers off, waiting for their big day on the ocean. Spaces for passing mariners, not surprisingly, have grown more expensive as the number available has shrunk. Sailors who are unable, or at least unwilling, to sustain the necessary level of spending are banished – visibly – to the far side of the fence. Soon there will be physical barriers to keep them out of the harbour too: the foundations are already in place.

The ripple effect of the ARC’s rigid berth occupation policy has spread to other ports on the island and, indeed, to ports on the neighbouring islands. Apparently some crews have even signed up for the ARC on the spot simply in order to avoid having to surrender their berth. The shortage of accommodation at this time is only exacerbated by the locals’ love of powerboats small and large, every one of which needs a berth. Hundreds and hundreds of oversize motorised bath toys sit bobbing in Puerto Rico, Pasito Blanco and Las Palmas, covers off, waiting for their big day on the ocean. Spaces for passing mariners, not surprisingly, have grown more expensive as the number available has shrunk. Sailors who are unable, or at least unwilling, to sustain the necessary level of spending are banished – visibly – to the far side of the fence. Soon there will be physical barriers to keep them out of the harbour too: the foundations are already in place.

These developments are in effect creating a two-tier society afloat, which seems frankly perverse in a sport that unites people of all backgrounds so seamlessly in other settings. Amplifying this divide, ARC yachts tend to be in better condition and to carry significantly more equipment than their non-ARC counterparts. Part of this must surely be down to the greater financial muscle of the ARC’s paying customers, but it is difficult not to start wondering whether at least some of the extra equipment on board betrays an attempt to buy confidence that is otherwise lacking.

These developments are in effect creating a two-tier society afloat, which seems frankly perverse in a sport that unites people of all backgrounds so seamlessly in other settings. Amplifying this divide, ARC yachts tend to be in better condition and to carry significantly more equipment than their non-ARC counterparts. Part of this must surely be down to the greater financial muscle of the ARC’s paying customers, but it is difficult not to start wondering whether at least some of the extra equipment on board betrays an attempt to buy confidence that is otherwise lacking.

For many sailors the ARC has to fit into a tight schedule: charter yachts need to be in place for the winter season in the Caribbean, cruising sailors on sabbatical need to complete their Atlantic tour. Away from the ARC, many long-term liveaboards march to the beat of an altogether more mellow drummer. It is no secret that the ARC starts too early for reliable northeast tradewinds, but boats need to arrive in the Caribbean in good time for Christmas in order to make the most of the opportunities in this renowned sailors’ paradise. The peak season for charter companies in the Caribbean begins at Christmas – and berths for the ARC typically sell very well.

Whether a later start date would have prevented this year’s problems will only become evident in subsequent years as trends in weather patterns and the response of westbound sailors become clearer. So far at least, the traditional mariner’s rule of thumb still applies: the later you leave the Canaries, the less likely you are to have to come back.

Whether a later start date would have prevented this year’s problems will only become evident in subsequent years as trends in weather patterns and the response of westbound sailors become clearer. So far at least, the traditional mariner’s rule of thumb still applies: the later you leave the Canaries, the less likely you are to have to come back.

The concentrated financial impact of the ARC fleet has become so important for Las Palmas and the island as a whole that local authorities now act as sponsors and provide services in kind by helping to absorb hotel costs and organising events. Add into the pot individual sponsors footing the bill for parties, firework displays and excursions and, at the end of it all, a farewell paella party for 1000 participants at which even the china threatens to run out and some at least of the assembled adventurers must be left contemplating who exactly all of this really serves.

The crews of course have plenty of time at sea for contemplation between the tension of the build-up and start in Las Palmas and the welter of events that awaits them in the welcome winter warmth of St. Lucia. Whether and how the festivities at the finish of this year’s ARC measure up to previous years will remain uncertain until not only the first powerboat, but also the very last of the sailing boats has tied up in St. Lucia. The shape of things at the moment though suggests there will be plenty of grounds to think again about the nature of events such as this if they are to remain attractive for the sailor as well as profitable for the organiser.

The crews of course have plenty of time at sea for contemplation between the tension of the build-up and start in Las Palmas and the welter of events that awaits them in the welcome winter warmth of St. Lucia. Whether and how the festivities at the finish of this year’s ARC measure up to previous years will remain uncertain until not only the first powerboat, but also the very last of the sailing boats has tied up in St. Lucia. The shape of things at the moment though suggests there will be plenty of grounds to think again about the nature of events such as this if they are to remain attractive for the sailor as well as profitable for the organiser.

Navigating an effective path through the maze of at times perfectly contradictory interests involved promises to be a Herculean task – on a par, indeed, with teasing out the best route to the trades and the fast lane West.

Peter Foerthmann

Good article.