ALL THE WAY AROUND … WHAT?

Haparanda: remote, mysterious, alluring… and located at the very top of the Baltic, so best enjoyed with the aid of some friendly sunshine. It’s really all about the journey, as every wise mariner knows, but even so some people need guaranteed sun and warmth to get them out of their bunk and for them a tour of the Med might be more appropriate (although a better relationship with the sun does come at the price of a trickier relationship with the wind, which tends in these lower latitudes to come in just the two sizes: too little and too much). But then every silver lining has its cloud, of course, and with that in mind I would now like to cast a critical eye over the routing options….

While not without its challenges, the well-trodden path to the Caribbean is hard to overlook. Wind on the quarter, sun from all sides: that’s sailing how they sell it in the brochure. Off the beaten track it isn’t, but even today the Caribbean undoubtedly has what it takes to set our dreams soaring. It has its disadvantages too (as a certain type of congenitally grumpy sun-deprived Northern European seems to take pleasure in explaining), but there is a strong case to be made for learning about them first-hand!

A few alternatives ( all standard disclaimers apply ):

– Stay a second season (this may include one or more games of hide-and-seek with angry forces of nature, so check the insurance)

– A trip up and down the East coast of the US (plenty to see, a fair chance of rain and easy access at all times to major airports with good links home for births, deaths and marriages)

– The short way back to the old world (this programme can cast a long shadow over a crew’s sojourn in paradise because the clock never stops ticking – the whole experience risks becoming a race from island to island, waypoint to waypoint with never enough time to stop and feel the sand between your toes)

– A deep breath and on through the Panama Canal into a whole new dimension of opportunities, possibilities and dilemmas. Enter the Pacific and Polynesia, still the non plus ultra of destinations, becomes a real possibility – the mystique, the remoteness, the intensity of sky and sea and, for the unreformed single gentleman, the hula girls (will dance for money)

New Zealand and Oz are hard to miss too (the ancients found them without so much as a pocket map) and the voyage to their shores – days and weeks at the mercy of the West Pacific and its capricious weather patterns – provides ample opportunity for every last soul on board to learn the value of humility. Resistance is useless!

Wonderful countries, vast distances… the thought of exploring the land away from the coast as well can become very enticing if the seed of the idea is once allowed to take root. Unfortunately though there are also inconveniences to consider, not least visas (never long enough), customs duties (always too high) and other encounters with the spectre of petty officialdom (polite enough on the outside, in the main, but sufficiently well-versed in the subliminal arts to leave visiting sailors in no doubt as to who holds all the cards). All of which explains why so many yachts shy away from running the gauntlet and turn again (and again and again) for another lap of the South Seas. The years pass and the same old questions continue to go unanswered until eventually the elephant in the room becomes too large to ignore: “How on earth do we get home safely from here?!?”

Down there, far from home on the other side of the world, sailors from all over the Northern Hemisphere find themselves confronted sooner or later with the need to make a decision: where – and what – next? Extended overland adventures offer sailors a completely different perspective and some conclude at this point that they have the best of their bluewater days behind them. The realities of a life afloat catch up with everyone in the end, don’t they? Some thrive on them, some consider them a price worth paying and some find in the end that their time at sea has only heightened their fondness for the things they miss (not least the chance to relax and enjoy all that the world of dry land has to offer without the need always to put the ship first).

Some people crave variety, an outlet. In ‘normal’ life, sailing represents that outlet, but what happens when sailing itself becomes normal life? What of the far-travelled sailor whose nostrils have begun to crave the scents of land? The change – in outlook, attitudes, priorities, desires, objectives – can creep over people quite imperceptibly over the course of prolonged periods at sea, but it is nonetheless irresistible. That particular genie is not for re-bottling. There are chroniclers out there no doubt who will take great umbrage at this and insist I have got it wrong and that the myth (the myth they chased themselves perhaps) and the reality are one and the same. Indisputably there are people who set sail fully intending to go all the way around and then simply have a change of heart along the way, especially when it begins to feel as though the best is behind them. Why deny it? What Pyrrhic victory awaits those who press on for the sake of an idea long after their love for the life has gone?

WHAT NEXT ?

If, on the other hand, the love remains strong, the question of how to navigate a safe passage home through the geopolitical complexities of the modern world cannot be ignored for ever. There are dangerous waters ahead, as seafarers of various persuasions have had forcefully brought home to them in recent years. German circumnavigators Eva Hauer and Rüdiger Tamm SV Sola Gracia for example, were still struggling to come to terms with their experiences in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea on Sola Gracia (two yachts close by attacked by pirates, four Americans murdered, another group including children held hostage) some time after arriving home and resuming life on dry land. Stories of piracy, many of them with awful consequences for the mariners involved, have become all too common over recent years (for those with an appetite for tragedy, see WORLD OCEAN REVIEW

PIRACY: THE WRITING ON THE WALL

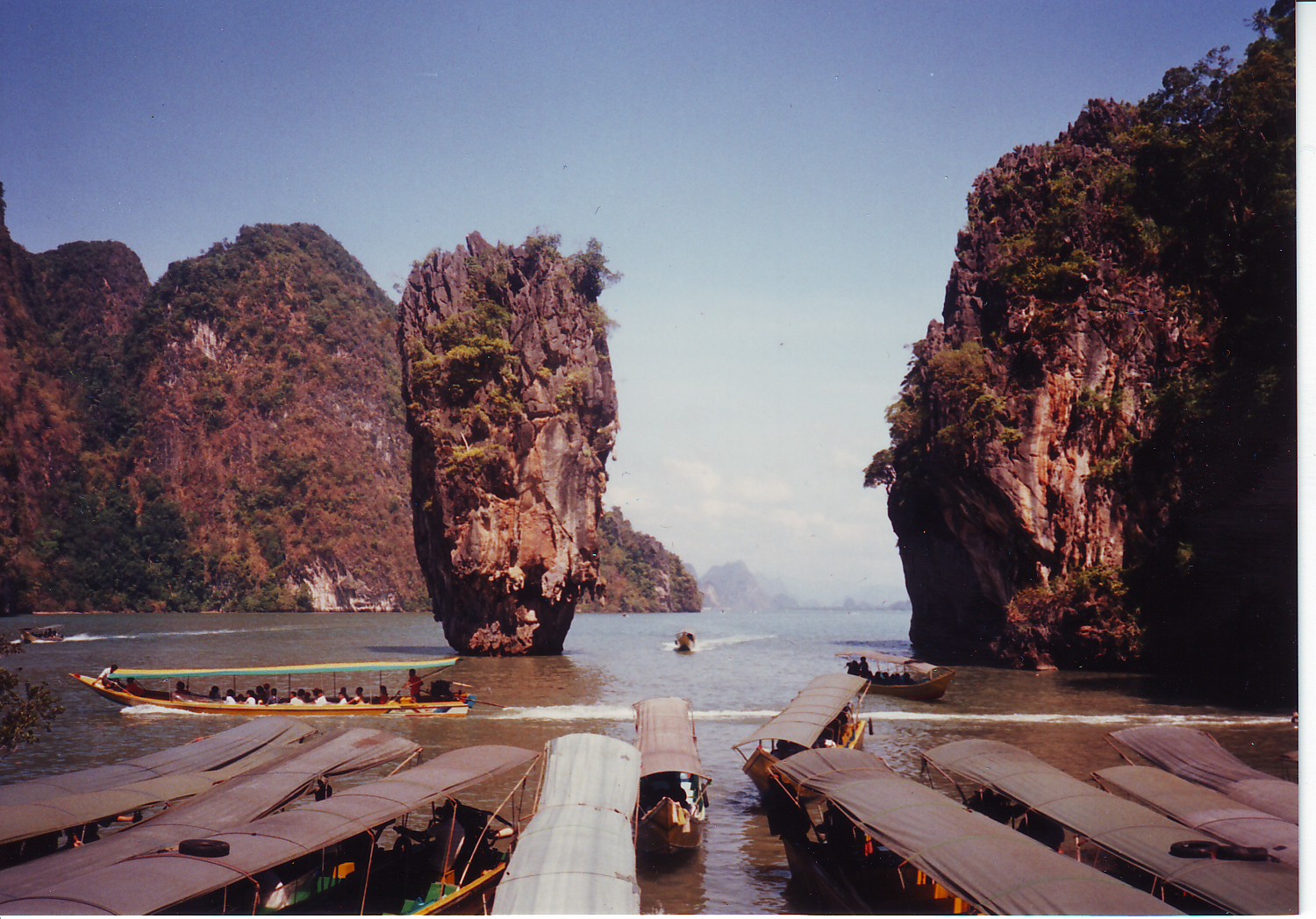

The threat of piracy looms large for today’s circumnavigators and largely explains why so many sailors seem to run into a dead end in the Far East, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand. The number of boats parked up in far-flung sailors’ meeting grounds while their crews – anxious to be moving on but even more anxious about what that might entail – wait for something to break the deadlock has been growing steadily for years. And as everyone must surely have noticed, the passage of time has not made the appearance of a safe path home any more likely.

The well-known trouble spots barring all of the obvious routes can make the prospect of onward progress in a typical sailing boat – a lightly-canvassed snail, in effect – seem as attractive as Russian roulette in the rain. In an age when even the smallest fishing boat or fast rib can easily be tricked out with the latest communication systems and gadgets, sailors make an easy target for unscrupulous types prepared to offer violence for profit. The kidnap of Stefan O. and Henrike D. in the Philippines in April 2014, for example, remains unresolved and we can only hope that diplomacy will bring a happy ending sooner rather than later.

Political developments in the powder keg that is the Middle East have obviously made a nonsense of any passage plans featuring the Red Sea and Suez Canal, but in Malaysia too, piracy has become a major concern and fast-moving small boats now need to be monitored very carefully to avoid the possibility of unwanted and unpleasant consequences. Beate and Detlev Schmandt SV Kira von Celle recently made the hazardous passage to Langkawi themselves with Kira von Celle. They are still recuperating after the stress of this particular leg of their trip and have yet to decide whether – and if so how – to continue.

I once knew a man on a world tour with a production GRP 36 footer who consider himself invincible because he’d fitted bulletproof glass hatches…

The number of boats on standby at the other end of the world confirms in unmistakeable fashion that the global sailing community has taken the hard facts on board.

OPTIONS and SOLUTIONS

COURSES

The way out for crews with the courage and capacity for a long, hard slog leads out far from land to South Africa and from there up to Brazil/the Caribbean and, eventually, the familiar waters of home. The shorter – and even tougher – option via Cape Horn remains largely the preserve of racers driven on by the unrelenting sponsors’ whip (and even they now usually have virtual waypoint “ice gates” to keep them away from the growlers). Both options promise a world of worry and discomfort for average circumnavigators, who tend not to view their voyage first and foremost as a sporting challenge and will not necessarily have procured or prepared their boat with such an extreme adventure in mind. Excursions this far off piste (and I say this without malice or prejudice – every crew has to make its own decision based on its own preferences and capabilities) really do separate the wheat from the chaff in terms of both boats and crew. The days of a relatively easy passage back to the Med through the Suez short cut certainly seem to be off limits for the foreseeable future.

RALLYING ROUND

Jimmy Cornell very much had his finger on the pulse when he launched the ARC in 1986. Originally a family event fuelled by enthusiasm and improvisation and delivered with the aid of like-minded volunteers, Jimmy’s idea has since spawned a worldwide rally industry involving all kinds of different event organisers that between them offer everything short of cruises around the local swimming pool and buyer guidance for prospective Oppi sailors. The now-familiar bluewater seminars first became established as a key element in the train of this new “guided sailing” movement.

A list of the various rallies around the world can be found here.

Jimmy Cornell has recently returned to global rally organising after a long hiatus.

The geopolitical developments that not so long ago laid waste to the plans of whole armadas of sailors simultaneously created fertile ground for the rally business, which holds out the promise of safety in numbers as well as the social contact so many in the sailing community fear they might otherwise miss on longer trips. Only those who have experienced the rally model first hand will understand fully what it entails and, most importantly, whether or not it works for them. None of the alternatives is without its drawbacks, of course, and such rallies are clearly growing ever more popular in bluewater circles; so much so in fact that entry numbers are often limited – and often limited to the harbour capacity of the destinations to be visited.

The scene in Las Palmas every November provides a snapshot of the rally experience, enabling anyone interested in the prospect to grasp the impact of 250 boats and their more than 1200 crew on harbour facilities, parties and clubs. Suffice to say it takes some getting used to (and not everyone will want to get used to it). The party atmosphere starts to give way to a more serious build-up after a while, however, and once at sea there is peace at last.

A glance at the long list of sponsors ( See here or here or here, for example ) shows what a big business the rally industry has become: these days event partners and supporters come aboard not out of neighbourly goodwill but because they can smell the profits to be made. Even hotels and airlines have signed up as sponsors (participants, friends and family need flights and beds, do they not?). Add in the contributions of tourist boards, harbour and marina operators, local service providers and technical support providers for participants and the organisers and we must be looking at a market worth millions. Now let me think… Who is ultimately going to foot that bill? READ HERE oder READ THERE oder AND THERE

The marketing looks after itself too: the nautical press ensures plenty of coverage, with journalists flown out and hosted by the event organisers (just to make sure they arrive safely of course). The journalists get their story (and their free holiday), the magazines their content and the event organisers their exposure. It’s a classic win-win, if you like (not me), the effect of which is to prise more sailors up out of the sofa to swell the ranks of the rally fleet – which is, after all, the object of the exercise. Interestingly though, as the size of the rally fleet has grown, so too has the number of boats choosing to shadow its progress – and share in its perceived safety in numbers – without becoming paid up customers.

Starting in 2015, World Cruising will be offering a round-the-world rally run on an annual cycle, enabling sailors to take a break when the need arises and return in time to continue with the next wave. For an eye-catching fee, a small, elite group of (generally quite large) boats is served up a full social programme, including press and parties, fit to fill every moment between arrival in one dream destination and departure for the next. The impact of these events on the venues they visit creates a certain amount of friction within the international sailing community, as the arrival of the elite fleet into port can leave everyone else feeling like second class citizens. Take Las Palmas once again, for example: the fleet descends and the ‘ordinary’ sailors find themselves shooed away by the harbour master into jam-packed anchorages to wait until the rally sets off and the pontoons free up again.

Unlike the ARC, which is timed to fit in with Christmas and the start of the charter season in the Caribbean and consequently attracts great squadrons of charter yachts, the US West Coast’s Baja Ha-Ha has managed to retain its family feel.

The nature of their craft and their choice of parking spots may have betrayed the underlying differences in budget to the educated eye, but for decades bluewater sailors of all stripes formed part of the same harmonious (if rather loose-knit) community. No longer! The modern hot spots for charter fleets and key transit points for rally sailors have witnessed far-reaching changes as residents and prices adapt to a different type of sailor-customer with different demands, different priorities and – a regular source of tension – different ways of behaving.

Charter boats loaded with clowns in holiday mode have a completely different agenda to the ordinary cruising crew with the time and interest to explore properly what each port of call and its people have to offer.

The wider sailing community has now begun increasingly to avoid certain destinations as a result of increases in prices and ‘upgrades’ to facilities demanded by event organisers (backed up by the threat, implicit or otherwise, of taking their hordes elsewhere if their needs are not met). Anyone dubious as to the power wielded by event organisers need look no further than the evolution of the marina in Las Palmas: for decades a scene of desolation and decay, today it wants for nothing (excepting users – it only ever seems to be fully utilised for a few weeks of the year, presumably because ordinary sailors do not feel its much-enhanced facilities justify its also much-enhanced charges). The decrepit old one-way-ticket crawlers that used to pass through from time to time have become a rare sight indeed in today’s Las Palmas!

Returning (for a moment at least) to the main thread of our investigation here, the question for us is whether sailing as part of a rally takes the risk out of dangerous passages. Given the current security situation in the world’s various political flashpoints, I think the answer must be clear to all. It is difficult to imagine any rally organiser being able to cope with the scale of liability involved. I recently asked Jimmy Cornell about this directly, but he was reluctant to go into much detail despite the fact that the website for his BLUE PLANET ODYSSEY still shows a route through the Red Sea. Perhaps he will be able to find a way to beat the odds?

SPECIAL DELIVERY

Hiring a delivery crew to bring the boat home requires exceptional trust and a faith in mankind of a magnitude seldom seen today: your boat disappears from view for months on end and with opinions as to what constitutes due care varying so widely from person to person, you have no idea what surprises may be waiting when it rematerialises.

SALE not SAIL

It gives me no pleasure to say it, but the option of trying to sell a boat lying on the other side of the world also entails a world of trouble. You might manage to find potential buyers who are interested enough to fly out (all expenses paid?) and inspect the merchandise and they might like what they see, but even then there is still the potential problem of the local customs authorities to overcome. In fact even simply leaving a boat in another country for a prolonged period can turn into a game of cat and mouse with the authorities, which know only too well there could be money to be made. Tax collectors the world over seem to have a particular interest in sailing boats and it can take considerable guile – or the services of a tax expert or lawyer – to elude their clutches. One person who cannot expect to make much money out of a boat sold far from home is the seller (an overview of the Reinke yachts for sale around the world can be found here). Market forces are merciless and very few boats sold in far-flung locations bring in anything close to the owner’s original asking price.

One person’s misfortune is another’s opportunity, however: in France, there are liveaboard families that roam the world looking for bargains they can sail back to Europe or the US and sell on – always through a broker – for a profit. I imagine it must be an addictive lifestyle for someone with the nerve, a little capital and a sufficiently free-spirited mindset to embrace this itinerant existence, family and all. For someone with the right background, the necessary knowledge of boats and access to willing hands, this unusual way of life could represent an attractive way to spend a few years on the move cheaply without growing stale or losing the love for sailing.

CARGO

Shipping your boat home as cargo is not as daft an idea as it might at first seem. The cost is not insignificant, but the benefits – provided one is honest about the alternatives – may well make it worthwhile all the same. A standard 40 ft container from Japan to Hamburg still costs less than US$ 1,000, although a fine sailing yacht will of course cost rather more (especially if the hard-nosed contractors of the commercial shipping world get wind of the fact they are dealing with an amateur – that’s manna from heaven in their eyes). I once had a 28ft powerboat delivered from Ft. Lauderdale to Mallorca on a float-on/float-off for US$ 5,000, which is precisely US$ 7,500 less than the price initially quoted to me in writing six days earlier. Prices go into free fall as the time of departure draws near, in other words, because at that point every additional order is seen as a welcome bonus. Clearly though this is no strategy for the faint-hearted!

Once the decision has been made that just sailing on home is not going to work, the yacht transport option is well worth investigating (see here or here and perhaps also here or even here). Not only do you have your boat back on home waters quickly for your own use, but you will probably also find yourself in a much more healthy market should your next move be to sell the boat. And thankfully today it is entirely possible to put your boat on another boat for transport by sea and still hold your head high around the marina and yacht club; indeed I know of a number of brave souls who chose this very solution even though it was never mentioned in the books.

THE DEAD END

Is my message then that trying to sail all the way around the world is no longer wise – or even no longer possible? The facts are there for all to see and I leave each to draw his or her own conclusions. The decision to pass through the Panama Canal is a biggie because from here on in, things get serious: the price of flights home becomes excruciating, visitors have to endure endless hours in the sky and airport lounges and while paradise awaits, it offers only a temporary distraction from the perils to come. People need to have a Plan B in mind in good time if those heady days among the the palms are not to deteriorate into uncertainty and anguish.

What began with the occasional seafaring adventurer has now become the subject of mass tourism. Even serious authors will have us believe high-volume production yachts are up to the challenge of a circumnavigation. Modern navigation and communication technology has greatly reduced the fear factor that accompanies the dream of setting out on the great round the world adventure, furthermore. Once upon a time every sailor had to be his or her own mechanic, but thanks to SailMail people with problems afloat now have access to dozens of virtual helplines and service engineers all over the world.

The nature of the typical bluewater sailor has changed over time too (if I can make such an observation without sounding too curmudgeonly), not least because the matter of available resources now plays such a big role. Money is no substitute for knowledge and experience at sea, of course, indeed some would say one of the great beauties of the sea is its capacity as a leveller, that way it reminds us that all of us are no more than so much spindrift. A quick look at how boats and equipment have changed over the decades though suggests the very notion of adventure has changed beyond all recognition. We sail in an age when the failure of a tool previous generations could scarcely have imagined – networked autopilots, GPS or AIS, for example – can trigger disaster. Truly the service society has taken to the waters and is crowing in plain sight at just what people can achieve in the modern world without actually lifting a finger themselves.

Many sailors ( principally the experienced ones ) still have the insight to understand the other side of the coin, however, to appreciate that every factor on which they rely at sea – right down to their own courage and capabilities and, above all, the toughness of their craft – has its limits. An honest appraisal of where these limits lie will naturally cause some to hesitate, to revisit and perhaps revise their plans. I consider this a process of natural selection and a thoroughly good sign: it shows that the lessons of a lifetime’s experience are still at the helm of the decision-making exercise. The inexperience (or is it pride?) of sailors who knowingly avoid acknowledging – and exploring the consequences – of their own limits promises nothing but trouble at sea, especially if this foolhardiness is exacerbated by hopes of making money from the venture.

Some will tell a different tale for sure but to my mind, now is just not an opportune time to be sailing around the world. Experience teaches us to think carefully and rationally about important decisions and one of the great strengths of the rational mind is its ability to drop or reorganise even long-standing plans if the risks become too pronounced. But what if the genie is already too far out of the bottle? What of the yachtsman whose friends, neighbours, colleagues and postman have all heard the grand plans and who cannot now see any way to back out and still save face? For people who find themselves in this position there remains one final, compelling argument to consider: ultimately you face the sea alone, with nobody to hold your hand and nobody to make things happen but you.

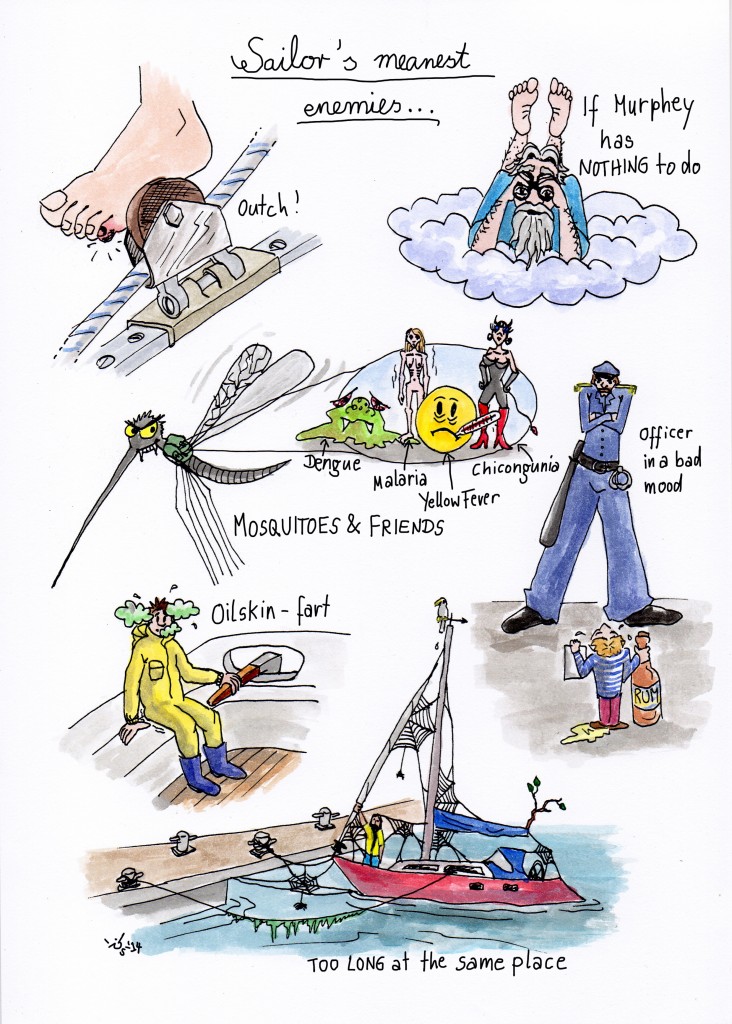

The constant worry about the delicate little anchor and the big fat boat dangling from it, the subtle piracy of the local port authorities, the endless visa dance, the terror of the weather forecast, the challenge of provisioning without importing stowaways of the four-, six- or eight-legged variety, antisocial social contacts, the never-ending list of boat jobs, the relentless burning sun… A trip around the world makes a wonderful dream if only reality doesn’t intrude too far.

The rapid expansion of the charter business around the world is no accident: many sailors like being able to realise their dreams one step at a time without having to worry about the bigger picture. An enormous number of sailors spend years afloat without ever venturing much beyond Southern Europe, moreover, suggesting that perhaps here too, wiser heads have eventually prevailed. And then of course we have the countless sailors who have grown tired of the Southern sun and retreated to home waters in the higher latitudes.

I have no desire to put a damper on anyone’s wanderlust. But there are spectacular destinations aplenty to explore in the more secure parts of the world if only we can shake off this myth that seems to hold us so tightly in its grasp: the myth of a carefree circuit of the Earth punctuated with beautiful bays for all to share and simple-minded locals with no other concerns than trading coconuts for glass beads.

Circumnavigation is no longer the top tip for sailors who put enjoyment first. There are just too many parts of the world now where properly serious serious stuff threatens to get in the way of the fun, suggests (with a measure of irony and an eye to his own shortcomings),

Peter Foerthmann