DREAMS AND REALITIES

Humans are social creatures at heart. Different people take different approaches – synthesis, synergy, symbiosis – but the life-long quest for true happiness in company (and its corollary, the emergence of new life) appears all but universal.

We snatch life experience after life experience from the jaws of life’s disappointments, ensuring that for as long as we can maintain the pace, no failure passes without a dividend of learning in due course. First the more primitive drives hold sway, but eventually the knowledge and wisdom acquired in repeated forays down the same old blind alleys gain the upper hand and life – we hope – begins to unfold in a more cerebral, directed, consistent and altogether more elegant fashion.

The evolution of life’s ambitions over time can follow any of a number of different patterns. Happy is he or she whose goals shine brighter with the passing years rather than fading one by one into obscurity, for with strong goals comes hope and with hope come an energy and purpose that endure until the final shuffling off.

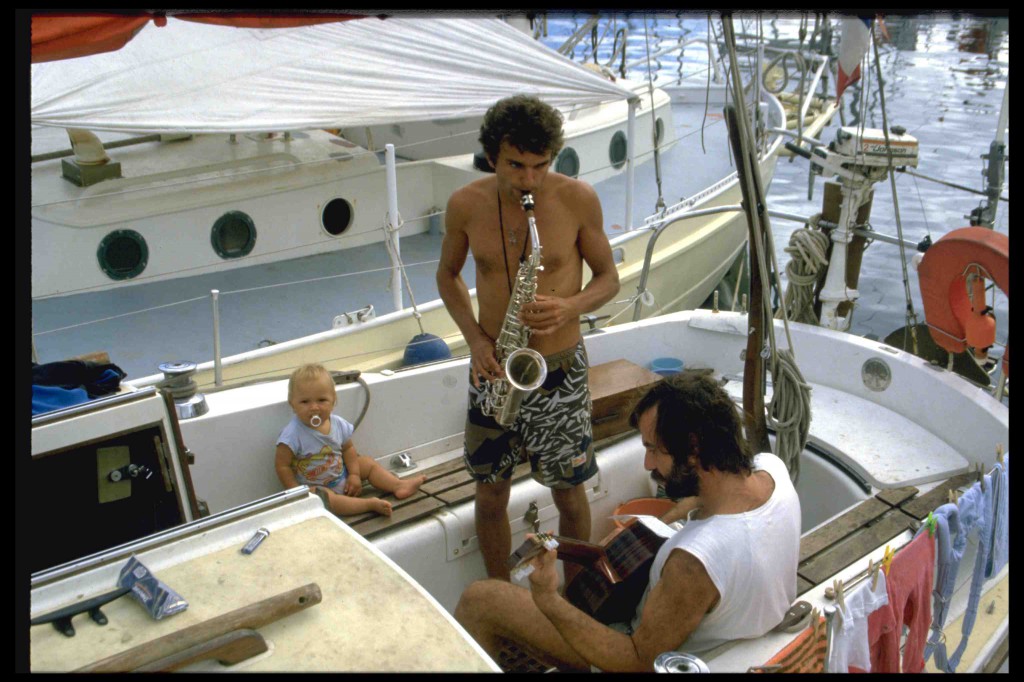

Those of us who sail in some ways inhabit a slightly slower-moving, less breathless version of the world. Perhaps this explains why sailors often share a rather different view of so many things and tend to have an affinity for other sailors that cannot be replicated in the ruder world of the landlubber. Sailors have to define – or discover – their own limits and once experienced, the magic of sailing is by no means limited to the water.

Dreams, the glue that binds our life together, can touch us anywhere: mighty inspiration can spring even from the most mundane of screensavers. But just as sailing draws people together, so it can drive them apart.

Nurturing and realising our dreams is what we live for; trying to fit too much into too little time how we end up living. We tread a narrow and tortuous path, made all the more treacherous by the bumps and banana skins of professional and, more pertinently, personal life. Which brings us nearer to the true eye of the storm: the crackling arc between the genders.

I firmly believe that an effective partnership represents the ideal, the non plus ultra, for sailing adventures. If two people can enjoy their sport together at peace with themselves and each other, with neither left clutching the short straw, neither merely following out of false promises or assumptions of a love that might more honestly be described as the need for an extra body on the foredeck, in the galley or, indeed, in the bunk, if two people can achieve this together they have truly scaled the heights.

Honesty and openness in a partnership help to reveal the depth of the shared thirst for nautical experiences: will it be the full lap of the globe or a trip across the pond? Or perhaps quiet hours alongside together tending the geraniums is the extent of the dreams to be realised: no matter – just so long as the team really lives as a team and not just as two lonely people sharing the same space and time.

Such harmony, it has to be said, tends to prove elusive: how easily external pressures and internal tensions put cracks in a partnership and drive the ship of life towards the rocks.This makes things difficult for men in the more traditional mould, as the alternatives demand decisions the wisdom of which only becomes clear at sea – and by this time it is usually too late to think again.

Any second thoughts do though tend to remain well tucked away in the soul of the solo sailing hero, who by nature would prefer to keep any concession of misjudgement far from the light of the sun.

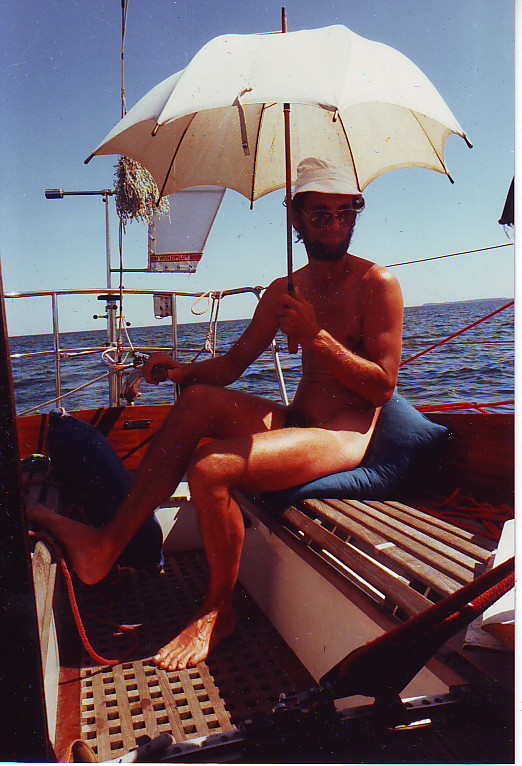

So what about single-handers? What can we discern of their particular dreams and realities?

People tend to assume all single-handed sailors are hard-core seadogs who think nothing of facing up to the challenges of the cruel sea, its trials and its perils, with only their boat for company. We pay them our respects – implicitly or openly – and mentally measure our own capabilities and courage against theirs, all of which serves only to enhance their standing as heroes (or perhaps not)

Single-handers can easily acquire legendary status. Their writings – seldom questioned and soon sharply etched in our mind – can plant the seed of an almost overwhelming idea in our mind. Thus fed and illuminated, our own dreams can develop sufficient power ultimately to drive a yacht to sea – with none other than us as skipper.

Some solo sailors come to acquire a quite extraordinary aura, making them an intriguing subject for further study, suggests

Peter Foerthmann

JOB OR VOCATION?

The desire to put to sea alone speaks volumes about a person’s willingness to open up to others and take a chance on learning to appreciate their company. Building an effective partnership is a lifelong undertaking. Challenging as the process may be, it can also prove much more rewarding than, say, regular visits to the psychotherapist’s couch. It feeds into an ongoing shared experience, usually involves deep affection – or at the very least mutual understanding – and the curative effects of life shared will achieve far more than professional therapy by the hour. The very best partnerships become perfectly symbiotic, a shared paradise, but while almost all of us dream of such things at least once in a while, few commit to tackling the challenges involved head on. When the going gets tough, as it tends to sooner or later, many head straight for the emergency exit or seek solace from the doctor. Or, of course, take to the seas alone!

Excuse the long introduction, but it seems only fair to provide some background to our rapid and largely unintended progression from discussing sailors’ shared dreams of bluewater voyaging to contemplating the profound mysteries of personal relationships.

Once underway, sailors who end up solo as a result of circumstance rather than conviction, that is to say those who have not been fortunate enough to meet and/or keep the right partner – or lacked the strength of character to ditch the wrong partner when there was still time to source a replacement – are unlikely to find much comfort even in port, as most of the people they meet will inevitably be either partnerships that are working or other single-handers like themselves.

Being left alone and suddenly – or even gradually – having to give up on the life afloat and the dreams of many years or reframe it all and take on the challenges alone can be a massive blow. It leaves a gaping emptiness – and not just in the next bunk. Those who decide to advertise this vacancy soon fall into the next honey trap: when unaccompanied sailors start offering bunk-space around, it’s definitely a buyers’ market!

There springs to mind a lonely mariner with yacht and Hammond organ I once met in Puerto de Mogan. He had hooked his virtual dream woman on the internet and was providing musical entertainment for the harbour while waiting to meet her in the flesh. She duly arrived – with rollercase in tow – but the unfortunate musician found himself a soloist again the very next day.

Usually the trials of a life together leave little doubt as to the suitability of a partnership for prolonged periods in a small floating space. And nobody can be expected to endure blowing chunks at sea for ever no matter how strong their love: feeding the fish day after day inevitably takes its toll.

It is when the time comes to cash in all the promises made earlier in life that countless would-be seafaring couples hit the rocks. Talking the talk is all very well, but talking doesn’t pilot boats across oceans. Each partner has expectations and eventually they have to be met – otherwise alternative pursuits are likely suddenly to appear more appealing. Promises follow a simple pattern: after the work, the pleasure. And the sums need to add up on the financial side too: no bucks, no babe!

First the career and the house and pool, then some kids to avoid (hopefully) a lonely old age and after that game on, promise! Promises like this, however well intended, have an unfortunate habit of expiring before they can be redeemed, in the process unleashing forces of potentially overwhelming power. All too often past assurances cease to carry any weight, the shape of long-professed dreams begins to change and shared ambitions fade in a welter of confusion and resentment. Gone with the wind! For partners alone together at sea a boat can seem as confining as a mousetrap – a mousetrap in which even the tiniest crumb of cheese can blow the lid off …

Too easily forgotten (or simply brushed aside) is it that the promise of this future is precisely what kept the breadwinner going through the seemingly endless years on the career treadmill. Was it all a misunderstanding? Not at all: just an excuse, plain and simple!

A growing awareness of persistent uncomfortable facts, the dawning realisation that all those promises – the foundations of the future – were nothing but so much hot air, seductive words spoken at the right moment not out of conviction, but merely to buy someone time to pursue their own agenda behind the scenes: would-be skippers can soon find life’s equilibrium shattered. Pity then the sailor who discovers life’s castle was built on the sand of misplaced trust just in time to contemplate having to re-imagine life’s dreams of a shared future afloat as a solo venture.

The rate at which yachtsmen all at once find themselves alone is known to rise steeply as the planned day of departure approaches. We becomes I from one day to the next; some adapt the programme accordingly, some just can’t. It tends then to be men who dream of single-handed sailing – the second-best dream they know.

German sailor Wilfried Erdmann once published a very funny and highly perceptive guide (in German only) on his website containing all kinds of valuable advice on how a yachtsman might go about helping a female companion with no significant sailing experience to become a competent yachtswomen and enjoy her time aboard. Men and women often differ in their essential enthusiasm for sailing and this alone can create tensions that reveal deeper issues beneath the surface: does she really want to? Or, to put it another way, does she mean what I thought she said or should I have been listening more carefully? Reproach – the mother of all misunderstandings…

It is surely no coincidence that bluewater couples often come together in their ‘second life’, share their sport for a few years and then plan the Big Trip with a conviction and vigour born out of solid experience.

Equally understandable, against this background, is the lively game of musical bunks that puts a grin on the face of customs officers and brings down the ire of the neighbours in so many harbours around the world! For those left over when the music stops there awaits the sorrowful one-way flight home: farewell ship, farewell skipper.

There are happy endings too of course. Take the story of a certain boyish Eva from Mainz, who found herself sitting sadly on a harbour wall in Spain at four in the morning one day a few decades ago after extracting herself, her suitcase and her dreams from a situation that had fallen short of expectations. Close by lay a master butcher from the same German city who decided on catching sight of this girl that perhaps he was not cut out for the single-handed life after all. Horst recognised very quickly that he had struck gold with Eva and that with her on board, two-handed sailing was much more to his taste: 30 years on they continue to live and sail together aboard their yacht Nele.

Life at sea as a twosome can be heavenly!

Much more commonly encountered are single-handers who pursue the sport as a strategic method of burnishing their own star in the hope of generating successful marketing copy. They play heavily on – sometimes overplay – the gulf between their exploits and the experiences of the average wage slave to help them sell their adventures all the more effectively to their shoreside brethren.

At their best, such tales can prove a winner for both author and readers, but as German multiple circumnavigator and sailing book author Bobby Schenk points out, writing books about boats is no way to fund a new superyacht: “For every book about sailing around the world that makes it into print, publishers receive twenty or thirty proposals. And only one or two such books are likely to be published in Germany in any given year. But then the money starts rolling in, right? Not quite! A book about sailing around the world can expect to shift between 2000 and 5000 copies and the author’s royalty – as can also be ascertained from the internet – typically ranges between two and ten percent of the selling price. This means that all in, a book about a voyage that lasts several years and circumnavigates the globe is likely to bring in around a couple of thousand euros – or about the same as a decent yacht radar system.” End quote…

It should be noted, of course, that while our sailing heroes all sit at the same table, they are by no means all pulling in the same direction. Each has to look out for number one and – all smiles – defend his or her niche vigorously against the sallies of the potential Next Big Thing. This fight for survival can quickly turn a simple boat show stand into hotly contested territory (luckily the shows also provide individual cubicles where people can set forth their objectives and unfold their tactics in rather more peace and quiet). Publishers and their assistants are stalked like rare game at boat shows as eager prospective authors vie to bring them to bay and deliver the most compelling pitch.

For all that few hopefuls ever make their way into print, an entire sector depends on these emerging writers, on spotting the new heroes, moulding and nurturing them and building their profile ready to share their exciting and entertaining experiences – for a fee – in print. The gently swaying palm in the mind’s eye of the average desk-bound sailor needs constant watering and there are always birthday and Christmas presents to be bought, new dreams to be fed.

I find it tempting to distinguish single-handers one from another on the basis of their commercial subplot. Teasers and epilogues all speak of a yearning to discover oneself and one’s limits, but all too often the text itself reveals other, perhaps less noble fascinations.

No objective is too bizarre to dangle like a juicy virtual steak under the nose of an eager, salivating public. And every new record seems to have the potential to unleash further absurdities. The pages are already so densely-packed with weirdness as to be approaching the colour of the black stuff, but the chance of a place in the Book of Records has lost none of its magical appeal.

MEDIA ATTENTION

is the name of the game, the altar that renders grown men and women seemingly powerless to resist and before which parents humbly prostrate their children. A little marketing knowledge can be useful here: we have now moved on to a pure numbers game, a multifaceted investment project in which genuine returns are expected. Nobody puts smart investment money in just for the experience. But wait, sailing as an investment? It hurts to talk about our sport in such terms. We prefer to see our sailing as something far more elevated, spiritual if you like: the cold hard figures may be on our tail, but we are always swift enough over the waves to outrun them. Whoosh – we’re gone! For what it’s worth…

The urge to take to the seas alone remains a fundamental contradiction, and one large enough to convert into a perfect investment. Sailing dreams as a commodity – if the bucks are big enough, the marketing men will be there almost as fast as the gold-diggers.

Segel Träume als Ware – Sternstunde für Marketing Profis – gleich hinter Dolores.

The more remote the hero’s life from that of ordinary folk, the easier it is to shape it into an investment. This applies equally to footballers, racing drivers and mountaineers as well as sailors, although in most countries the latter lack the recognition to raise more than a few from the comfort of the couch.

Investors have no time for sentiment. They want a return on their stake and they make no secret of it, so the concept behind the sailing project needs to be something special, ideally unique. The pressure is high, the pitfalls to be avoided substantial.

Bobby Schenk offers some words of wisdom on sponsoring too: “Finding a sponsor is child’s play – if you can make a convincing case that the deal will be profitable for the sponsor.” Now there’s just no arguing with that!

Nevertheless stories of the sea continue to seed dreams in the public’s mind of such vividness that the noise and stench of the commercial engine room quickly and easily fall out of mind. Why else do resilient Japanese gentlemen of advancing years sail tiny boats to the Golden Gate – where photographers stand ready to capture the necessary shots – before appearing in TV spots to proclaim at maximum volume the wonders of a particular beer?

Or what about the story of KAZUO MURATA, who mastered the Pacific in his Yokohama 22 as a 70-year-old beginner? His poetry and verse about the voyage and life at sea as a lonely man from Japan were published in a book

And then there’s the crazy tale of MASAYUKI KIKUCHI, another son of the rising sun, who set off in his yacht Beam intending to sail around the world in stages but instead fell victim to a series of accidents and breakdowns. Beam suffered all kinds of damage, turning Kikuchi into something of a one-man economic stimulus programme for boatyards in Hawaii, New Zealand, Argentina, Cape Town and Durban. The man himself remained determined and utterly undeterred – until he too sustained damage that could not be repaired without professional help. A knockdown in the southern Indian Ocean brought his adventure to a spectacular end: with both arms broken, he still managed to telephone for help and was eventually transferred to a cargo vessel after being located with the aid of a private jet owned by an Australian billionaire.

A tough way to finish no doubt, but it certainly made the headlines.

The oldest hand in the solo sailing business may well be KENICHI HORIE, who has been targeting and deftly plucking one record after another on a three- or four-year cycle since 1962.

Another contender is Swiss/Japanese yachtsman Seiko Nakajima, who bobbed across to Miami from Europe in his tiny yellow banana of a boat Seiko da Grindelwald with little more for company than a 2.5 HP Tohatsu outboard and a seat to recline on, was promptly impounded downtown by the US Coast Guard, disappeared again overnight and eventually turned up in New York, from where there was definitely no putting to sea again. His famous little boat today stands in the Museum of Transportation in Lucerne, Switzerland, while Seiko, also the inventor of a very neat mast ladder derived from mountaineering equipment, now makes his living as a hotelier.

Englishman Tom McNally, 65, from Liverpool certainly merits a mention too, although his plan to cross the Atlantic twice in 18 months – sitting down – in Vera Hugh II of Jersey, a boat just 100 cm long with a square sail and the rudder mounted on a sizeable extension aft, didn’t turn out quite as he would have wished.

Examples of smart marketing are plentiful really – just so long as the goal is not too implausible and the story not too incoherent. Readers are generally happy to give the adventurer the benefit of the doubt and enjoy the yarn on its own merits provided their hero refrains from laying it on too thick.

The way single-handed sailors are marketed in Germany is rather touching in comparison with other countries, perhaps in part because of the clear differences between the candidates and their approach to the water. The exception is survival expert and human rights activist Rüdiger Nehberg: he didn’t so much approach the water as sit in it. On a tree trunk. All the way across the Atlantic…

The story continues: there’s more (and more) to follow, promises

Peter Foerthmann

To be continued…