REFLECTIONS

A couple of decades in the stern embellishment business have given me the opportunity to set foot on, or at the very least cast my eye over, the great majority of the thousands of different yacht designs produced around the world. While I have an obvious interest in – and something of an obligation to consider – the rest of the boat as well, it is the aft end of the beast that I regard as my specialist subject.

The stern I view as my department and, quite logically, I have strong feelings on the subject. And my feelings, as it happens, agree entirely with my cold, hard rational side: I like the classic beauties of the stern world, those products of craft and vision that have rather fallen out of favour today thanks to the passage of time, commercial pressures and the fact that apparently providing standing room in the aft cabin of a 30-foot cruiser helps to keep the customers coming.

Is it perhaps because most boats now seem to be designed first and foremost as troop transporters? Because aesthetics have to take a back seat – some might say get off the bus altogether – in favour of more practical considerations like inserting the maximum number of bunks into the smallest possible LOA?

Today’s stern also has to contend with the various appendages tacked on to help the bathing beauties of the sailing world sashay more easily from deck to sea and back again. The modern sailor, it seems, is at the mercy of a charter-oriented design world with a strong penchant (what some might call an obsession) for fold-down features.

Those who hanker for more distant horizons, however, have more processing concerns than convenience in coastal waters: can components attached with but a few snap hooks or lashings really be trusted to withstand the probing attentions of an angry sea hour after hour, day after day?

On the other hand, the wide open spaces of the modern stern provide plenty of room for big-thinking bluewater skippers to accommodate (acquire and install) every last accessory. There they sit, like so many sparrows on a perch:

tender with davits, bathing platform to collect assorted flotsam, life raft with launching ramp, fender holders and bike rack, stern anchor for anchoring backwards (just in case), water generator for electricity, mounting system for wind generator (nothing makes the skipper grumpier than a turbine blade in the skull), solar panel board and radar doughnut (because the mast has enough heavy stuff stuck on it already) and whip antennae in various lengths for purposes navigational and personal (even at sea, your therapist need never be more than a phone call away).

“Oh and last but not least, we’ll be casting off in a few hours but we really need a Windpilot on there too, but it needs to go off-centre so that it doesn’t interfere with the swim ladder … and also funds are terribly tight so a special deal would be welcome – with a lifetime warranty of course – or actually maybe we could just have it as a sponsorship deal – it says Windpilot on it so really we’re doing your advertising for you…” I’m joking, of course – but not much! “And another thing, really the waterline needs to be raised up a little: now the boat is fully loaded it has disappeared down into the cruel sea.”

MY DEPARTMENT

Sometimes outside intervention (with all the finesse of a blunt instrument) is the only answer. Which brings us right back to where we started: sterns are my department and, given the necessary willingness to hear and accept alternative opinions once in a while, I can help bring harmony to the riot of add-ons seeking a home at the blunt end. The key, of course, is proper planning: owners need to plan their stern layout carefully and in good time before the jungle of brackets, cable and hardware begins to sprout.

And so it is that most of my time spent assisting yachtsmen comes to be dedicated not to my own immediate field but rather to striving – sometimes in the face of a most spirited defence of the status quo – to bring some clarity as to the essentials and optionals of boat and equipment, to helping the crew distinguish between things they really need and things they have just always had or wanted (like the BBQ on the pushpit) before they receive a punitive lesson on the same subject from the elements. As we all know, a few nights at sea can make a nonsense of what seemed like perfectly sensible priorities on land: poor planning takes a hefty toll, especially if it leaves expensive gear disembarking through the emergency exits. We live and learn; that’s part of the job description of being human.

Life is one long chain of decisions: get an important one wrong as a long-distance sailor and the consequences can be overwhelming. My aim, without wishing to sound too evangelical, is to help guide the decision-making process in the right direction, to shift the focus, sometimes in a very practical sense, in order to avoid later disappointments and ensure – at least on the inanimate side – that the boat remains a happy place to be.

But enough of this abstract reflection: let us put some meat on these bones.

DECISIONS

I would like to begin with the observation – unsupported in this instance with either compelling argument or boisterous sales statistics but hopefully uncontroversial nevertheless – that choosing the right self-steering solution for a boat is not just a potentially complex decision but also a critical one. Or, to put it more bluntly, bluewater sailing with a small crew is only even conceivable for most of us thanks to the visible/invisible little helper at the helm. There may be many facets to the call of the ocean, but I think it safe to say the prospect of endless hours at the helm fighting a hopeless battle with drooping eyelids has never been one of them.

Of course every offshore yacht today comes with an electric autopilot as standard – even those whose crew also appreciate the company of the silent self-steering alternative. I do not intend to examine the reasons for this at this juncture; suffice it to say that, despite all predictions to the contrary, mechanical windvane steering systems have pointedly failed to go extinct and are in fact in rude health, with several dozen manufacturers around the world making an enjoyable living on the back of the fact that there is life beyond the autopilot endless loop.

Many years ago it used to be considered a triumph in an event like the Vendée Globe if at least one of the typically twelve or so reserve units generously provided by the sponsor survived to reach the end of the race in operational condition. And anyone like to guess what Harald Sedlacek dreamed of when the autopilot on his FIPOFIX gave up the ghost and left him more or less permanently attached to the tiller for weeks? I find it difficult to comprehend really, as his father Norbert, whose career path to offshore racing took an unusual diversion through a spell as tram conductor, made sure always to have a Windpilot on hand for the manual labour during his circumnavigation. I wonder, when does confidence become overconfidence and how much prudence is too much prudence?

The use of mechanical wind-driven steering systems is increasing even in the high-speed French Pogo fleet, while all over the world skippers of cruising yachts of all sizes, driven to their wits’ end by the inscrutability of a malfunctioning black box (and a profound yearning to hear the pure sound of the sea again), are finding themselves drawn back to the silence, simplicity and reliability of mechanical windvane steering systems.

Recent examples include Jean Claude Fleuret, who ordered a system for his JFA 35 Suditude from Chaguaramas in Trinidad after various unnerving experiences and is now on the way to Chile. Here is his initial assessment:

Hello Peter,

We are arriving in Testigos 11 22 N, 063 07 W, N of Venezuela. First trip 0f 98 NM with your machine. 13 hrs. What a regal !!! Fantastic! We have back wind, light (no more than 12 knts) and a little sea from NE.

Your machine hold perfectly the boat. Thank you a lot.

Kind regards.

Jean Claude

The moral of the story? When choosing boat and equipment, decisions need to be made for the long term and with a clear understanding of what is required. Every misjudgement comes at a cost, sometimes just in the form of potential enjoyment lost, often in the form of genuine pain both financial and emotional.

THE “EXPERTS”

Specialists of every calling, flotillas of authors with or without hands-on experience, journalists employed and otherwise – the self-styled “EXPERTS” in other words – go at it hammer and tongs to create a distinctive angle or advance the case of their connections. The extent to which a given desk-jockey’s quest for literary originality or commitment to the party line overlaps with the interests of the seafaring readership emerges only later, when waves and weather grant Mr and Mrs Yacht Owner the pleasure of discovering first hand just how far theory and practice can be made to diverge.

Word of mouth provides a much more reliable measure of user satisfaction: the marketing tool par excellence, it works brilliantly among sailors the world over. The first-hand experiences of our peers carry real weight, not least because they often give an insight into the human as well as the machine. Nobody has a monopoly on self-deception, but there can be no doubt some are more willing than others to apportion all the blame honestly: as in all things, forthright remarks from people unafraid to acknowledge their own limitations seem to leave the strongest impression.

THE COMPETITION

The progress of the head-to-head between the various marketing approaches – glossy ads, advertorials, quid-pro-quo articles and reports – and the combined practical experience of actual sailors doing actual sailing can be assessed by looking at sales figures for relevant books and magazines. And the clear trend, worldwide, is that as the power of the printed word plummets, so the voice and views of the ordinary sailor ring out ever louder and clearer through the medium of the internet (it gives me great pleasure to help these voices and views be heard: the Windpilot bluewater portal proffers thousands of links through which anyone with an interest in the subject can “download” hands-on info direct from other sailors).

This game-changing development has begun to undermine the whole nautical publishing edifice. Where once there was fairly easy money to be made sharing – for a not inconsiderable charge – the life experiences of a handful of prominent yachtsmen, today authors are increasingly finding the fruits of their labours flogged off cheap or offered back to them for pocket change to save their publisher the storage costs, in the process wiping out any prospect of the hoped-for royalties and leaving sailor-authors in no doubt that if their objective was to reach the yachting public, they backed the wrong horse. The battle between authors tied to publishing houses and those with their destiny in their own hands continues to rage. Electronic publishing is shaking the foundations of (once-)venerable print dynasties, leaving them with little choice but to learn the lessons of the new marketplace double-quick or drown in the mire of their own cost structures.

I firmly believe that first-hand experience is almost always the most valuable resource for bluewater sailors. It addresses pertinent issues with a currency and freshness that clearly trump the stale, entrenched opinions we see recycled year after year in new editions that eventually benefit nobody but their author and publisher. I find myself reminded at this point of the words of BOBBY SCHENK, who once remarked with such searing insight:

… it’s easy to spot a successful publisher: he’s the one slurping champagne out of the skulls of his authors.

THE QUIET HEROES

With all due respect for the big names of German bluewater sailing, who ascended to fame principally thanks to their ability to combine their own interests with those of their publisher, I reserve my strongest admiration for the quiet heroes, the people who have carried on away from the spotlight achieving remarkable feats without ever receiving (or indeed seeking to receive) the publicity their exploits might be considered to merit. There are thousands of adventurers under sail around the world undertaking sensational voyages in pocket cruisers and reporting near-live on their experiences. Lin and Larry Pardey from the US have been exploring with Seraffyn for decades, building a legendary reputation at home that their unflinching modesty over the years has only enhanced.

BRIEFING FOR THE JESTER CHALLENGE

The yachting world is full of quiet heroes who spend their days at sea achieving remarkable things without immediately reaching for the megaphone to burnish their own image before the landlubber contingent. I do not wish to speculate as to how many thousands of manuscripts have been submitted to our esteemed publishers only to be rejected out of hand on the grounds that the material appears insufficiently spectacular or that it would simply be too much of a challenge to build up a new generation of heroes without upsetting the market for the existing band. Our publishers reserve passage through this eye of a needle for a chosen few, artificially limiting the number of new books to appear every year and ensuring their established pricing arrangements endure (there seems to be a belief in publishing circles that the market has a very limited appetite for heroes and that consequently it is best for marketing and the bottom line to promote just a few: increasing supply, the thinking goes, would impact directly on sales and prices).

An element of craziness, something wild, wacky or just plain foolhardy appears to be essential to gain media interest today, which more or less rules out anyone whose sailing ambitions focus merely on sailing. People have a natural tendency to seek recognition and sailors are most likely to catch the public eye by planning something spectacular enough the set the media salivating, to persuade the journalists to become involved and follow closely how the self-proclaimed protagonist endures the inevitable ordeals to come. This being the case, we can confidently assume that the endless stream of freshly-minted objectives, embellished, exaggerated and idolised by their inventors as the very meaning of life itself, will continue to flow for as long as fame, honour and filthy lucre beckon temptingly from the other shore. The point of such ventures is always formulated and justified in the head of the protagonist and, as the case may be, that of a partner in life and love whose sufferings serve only to spice the dish. Nautical publicity-seekers with a gift for the PR game dominate the attentions of the media at the expense of the quiet heroes, whose genuine achievements offer less scope for immediate financial gain.

I am convinced that the shift away from print media in favour of the virtual world is going to shake up this established order beyond all recognition. Take the growing reach of e-books, for example: suddenly sailing heroes of a different strain altogether are going to be able to share their knowledge and experiences with the wider public without first having to cross the publisher’s palm with silver or pass the wackiness test. Prospective authors will soon realise that the returns to be gained via the independent route can not only equal but actually outweigh the remuneration promised by publishing houses – whose punitive pricing can easily make a mockery of their planned sales volumes. As it happens I speak here from personal experience rather than remote observation: my book Self-Steering under Sail was published by Adlard Coles/International Marine (in the US) in 1998 in an edition of 12,000 copies and then went out of print. However the PDF version has been downloaded around one million times over the subsequent twelve years.

A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE

There are exceptions – quiet heroes – with much to tell us all over the place if we just open our eyes and look beyond the confines of a fourth estate whose judgement is, indeed has to be, coloured by the dictates of advertising revenue. The fact that watersports magazines today restrict contributions to their online presence to just a hand-picked selection of their own authors renders unmistakeable the helplessness of the entire sector in the face of a development whose momentum has now grown to be unstoppable: more current than any book and dripping with the authenticity imbued by the absence of any profit motive, blogs are the medium of choice for the modern sailor. This leaves conventional publishers between a rock and a hard place, because sailors are quite clever enough to run a rule over virtual offerings and reject the click bait and the overtly commercially-motivated contributions that conceal anything of interest behind an obstacle course of pop-ups or restrict access to anyone reluctant to register and pay first.

I digress? It’s unavoidable: the market for authors is evolving fast and the tools now at our disposal open all manner of doors if only we can recognise them.

PRACTICAL EXPERTISE

The implications of making the wrong decision when choosing a boat can hardly be overstated. Realising that the boat you have bought is not the right one for you must be at best highly disruptive. One family who found themselves in this position are the Woehls from Flensburg in Germany, whose story is recounted here.

If, on the other hand, you find you have chosen the right boat, relax: there are still many ways you can get it wrong fitting out, but none of them will necessarily be life-threatening! Bad choices do of course tend to come with a price tag though. Bobby Schenk maintains a “Who’s who” section on his website (in German) in which he extracts and succinctly conveys practical experience from bluewater sailors by asking all returning circumnavigators the same questions. Their responses speak volumes.

Elaine Bunting von YACHTING WORLD edits the magazine’s Atlantic Gear Tests, which record the experiences of ARC participants every year.

A CAPITAL ASSET?

The value of yachts, as we are probably all painfully aware, has changed fundamentally over the last decade: once an asset that largely held their value, today most boats depreciate at a significant rate because supply has overhauled demand (and scrapping old boats is not yet seriously on the agenda).

The dream of owning a yacht of one’s own is tantalising – and all the more so when it appears surprisingly inexpensive to realise. The surprises do not end here though: boat changes hands, boat project commences, boat’s extraordinary ability to consume money starts to become apparent, nerves begin to fray… When embarking on a large-scale refit it is best to avoid checking the bank statements if at all possible or, alternatively, to try and prepare mentally for a financial disembowelling (or just start right away on the antidepressants). Most boats could not be further from capital asset status, especially if there is “a bit of work” to be done. Such projects can prove toxic to relationships too: happy the sailor whose partner stays true through this phase of the sailing experience!

Johannes Erdmann’s website provides an illuminating example of the reanimation of a GRP yacht (the text is in German but the many photos speak for themselves).

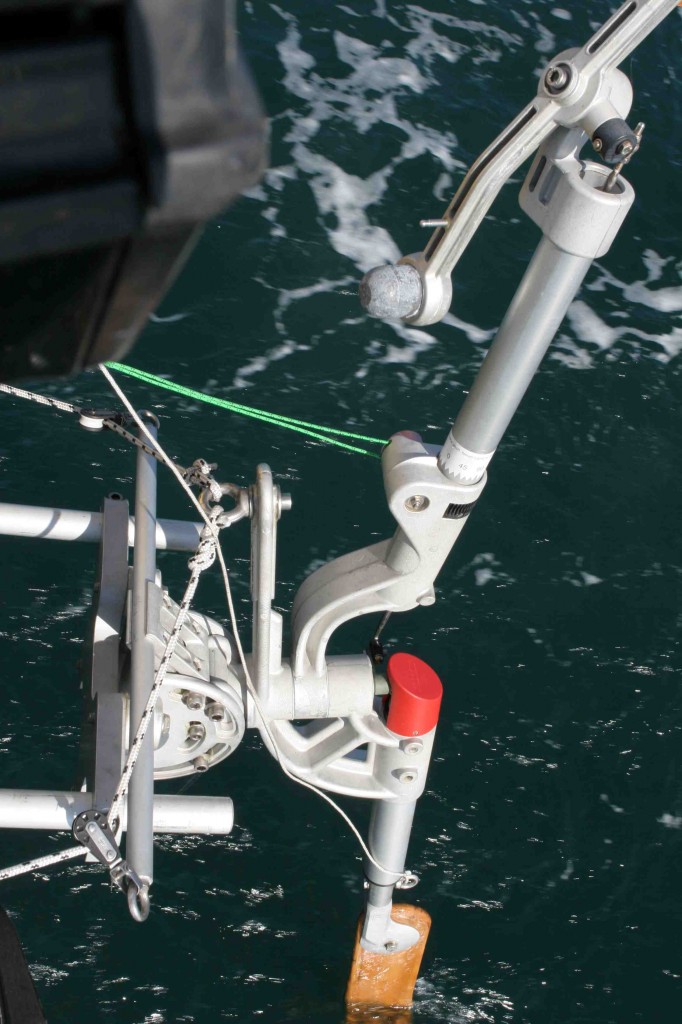

BUCKING THE TREND

Most on-board equipment loses value in step with the boat itself as a result of technical developments or wear, but mechanical windvane steering systems are rather different; in fact provided they come from a reputable manufacturer, used windvane systems usually depreciate very slowly indeed. The prices commanded by pre-owned units of my own brand in marketplaces such as eBay sometimes leave me mildly concerned: demand has driven up bids for at times pretty ancient systems to such a level that while sellers are certainly on to a winner, buyers may not always end up so totally satisfied.

The key to avoiding disappointment, as ever, is timely advice. And that is where I come in, sharing my knowledge as openly as I can in books, blogs and so on and always trying to tell it straight even if my advice to buy the cheaper of two potential systems, for example, might sometimes appear (superficially at least) to run counter to my own commercial interests.

BAD ADVICE

Bad advice – often euphemistically referred to in business circles as “a misunderstanding” – quickly becomes all too obvious at sea: a couple of nights under sail usually suffice to reveal any glaring mismatches between theory and reality. Such mismatches between theory and reality in the realm of windvane steering systems have truly hideous implications, because the boat always needs steering and if the mechanical solution can’t cope, the only other option is you.

I have enormous respect for any sailor prepared to recognise bad decisions, correct them and venture back out onto the seas again to do it all properly. It takes great strength of character to acknowledge our own mistakes, especially when the cost implications can be grave.

Now I find myself moving into more sensitive territory. I am of course just one of 30 manufacturers worldwide, but I believe the extent to which my company’s designs and features have been “interpreted” by others in all kinds of different countries sets it quite apart in the market. Rather than remaining in a state of constant agitation about this I have chosen to take it as a compliment: that so many of my competitors have “found inspiration” in my product concepts suggests I am probably on the right track. Price is not everything either, not when there are critical technical differences with critical implications to consider and not when resale value depends on the strength of demand. This, unfortunately, is a lesson poorly-advised sailors continue having to learn to their cost.

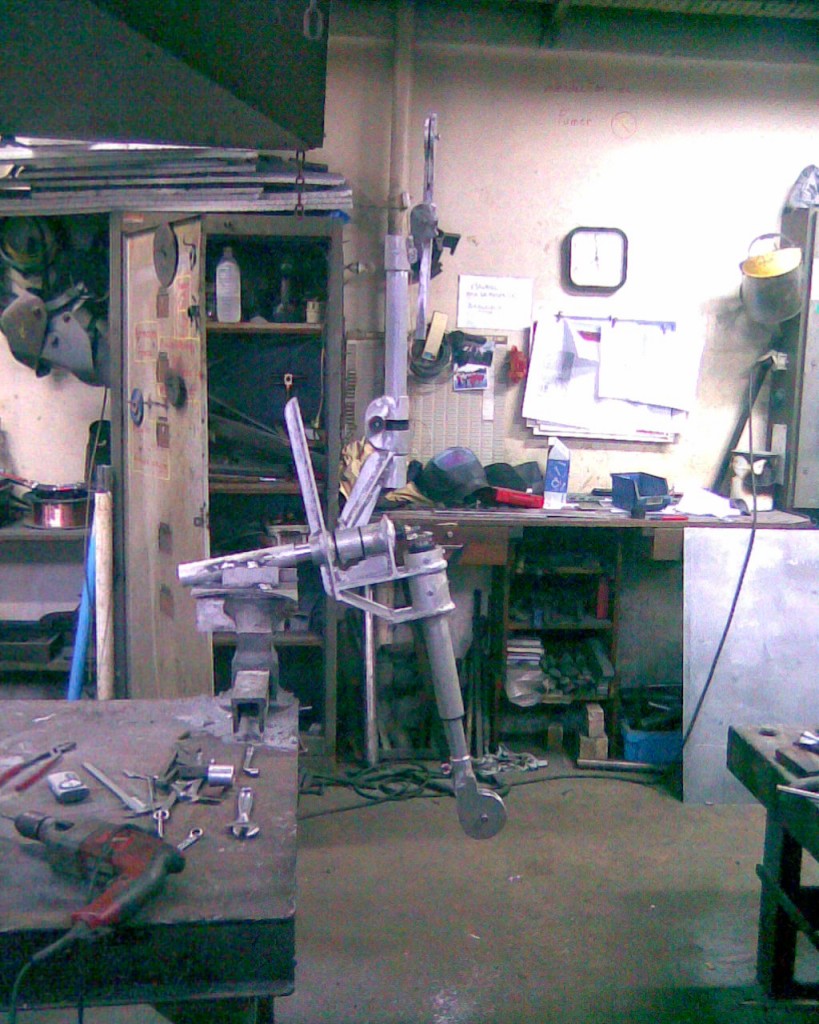

COPYCAT DESIGN

DIY or professionally built, outsourced or made in the EU, copycat producers cannot escape the rules of the market, which operate worldwide. The necessary conditions for global success today are:

– continuity in the marketplace,

– an appetite for innovation,

– a modular, technically refined product,

– proper customer service from start to finish and

– a brand that combines all of the above.

Germany’s smallest global market leader, we keep ourselves competitive at the international level by using industrial manufacturing approaches. This is the reason I still sleep soundly at night, at least this and the knowledge that word of mouth carries great weight among sailors – and comes for free to those who play by the rules and give their customers a platform to report.

Presented below are a few examples of people who bought once, had a change of heart for whatever reason and then bought again.

BEFORE AND AFTER

SV Marianne, SV Marianne, Ben Schaschek and the Sailing Conductors GER

SV Marianne, SV Marianne, Ben Schaschek and the Sailing Conductors GER

SV Trotamar, Joan Bassols BE

SV Trotamar, Joan Bassols BE

SV Arwen-of-B, Klaus W. Martinique French W.I.

SV Arwen-of-B, Klaus W. Martinique French W.I.

SV Inge, Ben Wedlock march 2014 in Falklands expecting delivery of his new Windpilot in Port Stanley

SV Inge, Ben Wedlock march 2014 in Falklands expecting delivery of his new Windpilot in Port Stanley

SV Panika, Krystyna + Andrzey Plewiki US

SV Panika, Krystyna + Andrzey Plewiki US

Belt and braces – take two and you should be ready for anything.

SPONSORSHIP

If I embraced every one of the requests for sponsorship (in the form of a free Windpilot) that comes through our door, I could easily ship a year’s worth of production without selling a single unit. But what good what that do? Would that help my business? Would you not expect a sailor who received his or her system as a free gift to make a special effort to say nice things about it? Should I be in effect paying sailors to spread the word that my systems really work? And would their views count for anything if I did? I believe word of mouth is the better way – and it’s fairer too: my customers get peace of mind to enjoy their bunk on passage and I can make a living from my labours!

Sponsorship has never really broken into the mainstream in German sailing, not least because the whole idea is so often misunderstood. Typically the pitch runs something like this: “You give me a lollipop and I’ll find ten different ways to say how good it is.” Poorly-drafted agreements and run-away egos not infrequently derail the deals that do emerge too, to the dissatisfaction and disadvantage of both sides. The German sailing scene is littered with such misunderstandings: sponsorship at a professional level demands well-resourced companies ready and able to invest in and capitalise on campaigns, but the German market is just too small. And while trading merchandise for media exposure has become a slick and omnipresent model in other areas of life, making it work in sailing poses big problems due to the lack of people willing to pay.

Wolfgang Quix made a determined effort over many years to find well-resourced sponsors for his yacht JEANTEX. Despite being one of the forefathers of German bluewater sailing he never succeeded in this particular venture and eventually sold his boat.

SPECIAL MISUNDERSTANDINGS

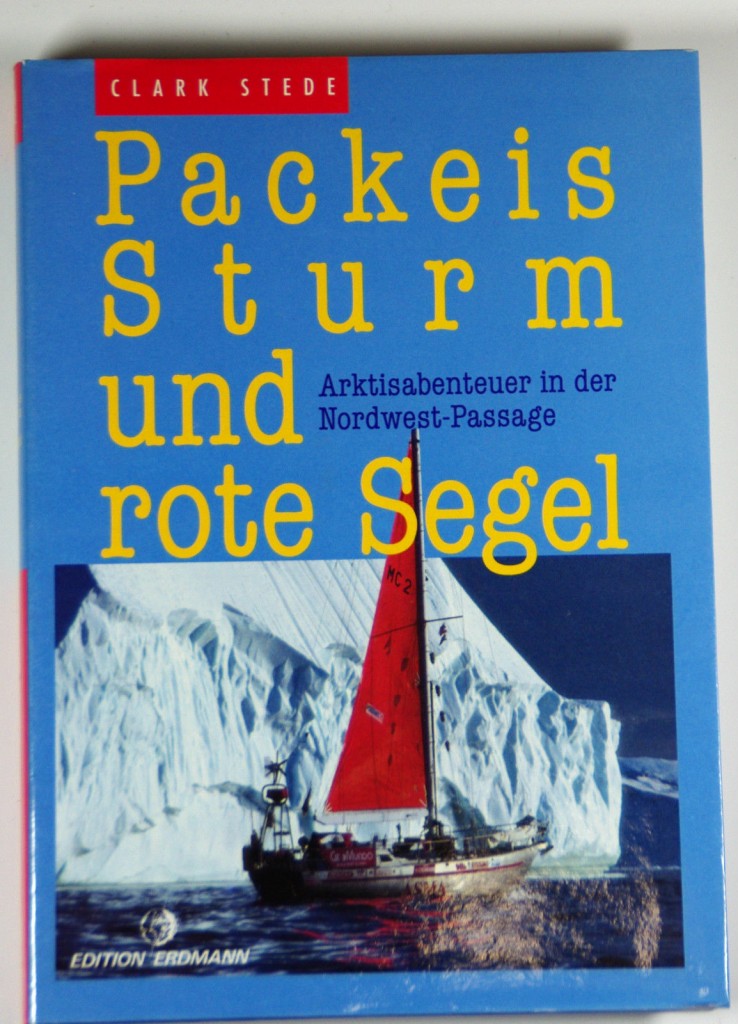

CLARK STEDE

Decades ago I embellished the stern of Clark Stede’s yacht Asma at what we might call a friend’s discount. When I saw the first photos of Asma in action, prominently featured on the title page of Germany’s YACHT magazine, I noticed the striking seascape and towering ice cliffs, of course, but mostly my eye was drawn to the ludicrous position of my Windpilot’s rudder blade, the result of the owner having welded a bar around the unit to fix a non-existent safety problem, in the process rendering the lift-up feature useless and forcing him to fit and adjust the blade by hand, which he was never able to do properly. When I met Clark later on at a boat show, he informed me that my system didn’t work very well (really?) and that he intended to replace it with an American model (with which he then experimented and eventually achieved satisfactory results – or so the story goes). So much for the win-win of sponsorship! The boat, now the TAONUI, went on to become globally renowned under subsequent owner Tony Gooch. My Windpilot may well still be hanging trophy-like on Hans Bernwall’s wall somewhere over there in Oakland, California.

BERND LUECHTENBORG

I doubt anyone has done more to scare sponsors away from German sailing than Bernd Luechtenborg, who left his commercial backers and especially his media partner YACHT magazine in absolutely no doubt as to where they stood in his order of priorities. I am amazed that the media partner has still to share the story with its readers, although perhaps its natural interest in the decidedly juicy details of the tale is out-gunned by the sense of embarrassment at its own involvement. Here’s a comment I posted on the YACHT magazine forum in 2010 (still hiding behind a pseudonym).

LAURA DEKKER

I confess, I broke my own rules and sinned against myself: when Laura and her father Dick Dekker came to visit me at my workshop in 2009 (when she was just 14) with the intention of buying a Windpilot system, the plan explained to me by this thoroughly unpretentious young adventurer almost moved me to tears. I handed over a Windpilot system as “sponsorship” with a glad heart for the very first time and even travelled to Holland to upgrade it when she changed boats, so momentous did the whole undertaking seem for someone so young. The story captured the headlines around the world. Less well known is the fact that I never heard a word of thanks for my contribution.

JOHANNES ERDMANN

An amicable and enthusiastic young man appears, eager to learn and bursting with plans that remind us in many ways of our own dreams of youth; naturally we want to help him, especially as his ambitions clearly run far deeper than his pockets. Sometimes we all need a little boost to get our projects off the ground, so why not lend this young sailor a hand, offer him reduced rent and help him find his way to a favourably-priced windvane steering system?

Misunderstandings in human relationships spring so often from a shift in priorities: our judgement as to what constitutes a fair balance just seems to change when other considerations (possibly including a financial element) slowly but surely take over the controls. For a journalist, however, professional success is founded in large part on credibility, so it will certainly be interesting to read why a once passionate advocate of the Windpilot brand suddenly sold his system in favour of another!

The rules of human interaction are subject to constant personalisation (or, to put it another way, some people are always looking to get more for less). All too frequently ego trumps everything else to leave empathy floundering in its wake. Thankfully I inhabit a world shared by a large number of people who put company and comradeship before the daily rite of feeding the ego and chasing the next dollar, a world in which respect – respect for other people and respect for the natural stage on which our adventures under sail unfold – genuinely matters.

It may have given me the odd grey hair (just one or two – I’m sure nobody has noticed), but it is a world that allows me continued pleasure in my work even after all these decades.

And for that I remain a grateful

Peter Foerthmann

Lieber Herr Foerthmann,

Yachten führen seit Jahrzehnten mit allen möglichen Heckanbauten ohne Probleme größere Reisen durch. Warum sollte hier ein größeres Risiko bestehen wo wir doch bei Spaziergängen durch Marinas mannigfache, erfolgreiche Ausführungen vor unseren Augen haben. Zumal hier doch so deutlich des Skippers Möglichkeiten hinsichtlich Portemonnaie und Technikverständniss demonstriert werden können, Auch die breiten Hecks, möglichst mit direktem Zugang zur See und daher ohne Cockpit-Aufbau verdeutlichen, wie unsinnig es ist, über die Sicherheit der Crew kritisch nachzudenken. Was soll das, eine Yacht ohne ausreichend großzügig dimensionierte Liegemöbel ?

Hier sind Sie wieder mal so übertrieben kritisch.

Was bewirken schon Tonnen von Wasser im offenen, breiten Cockpit bei Talfahrt in einer hohen Welle.

Nein, Sie liegen hier falsch wenn Sie auf bewährte und aus langjährigen Erfahrungen resultierende Ergebnisse zurück greifen.

Bedenken Sie bitte auch, dass mittels weltumspannenden Informationen niemals Schwierigkeiten entstehen, auf die neue Gerätegeneration kann Skipper sich eben verlassen. Jetzt wird Ihnen sicherlich klar, dass Ihre Kritik etwas altmodisch erscheint. Der Fokus des neuen Yachtdesigns hat daher Berechtigung, auf Party und SPA ausgelegt zu sein.