Tears and anguish are a night-time tradition in the Canaries, at least when Europe’s migrating sailors pull into port every autumn. Descending locust-like on the supermarkets, they buy up crates of beer and bananas, pampers and milk as though supplies everywhere else on Earth had run out. Smart yachts sit ever lower in the water as more and more provisions are stowed. Shopping keeps the sailor’s mind from wandering – a welcome respite when the default setting of so many minds at this stage of November is good honest bowel-churning fear. Nobody speaks the question aloud, but the whispers rising through the jungle of masts and flags are almost deafening: “to go or not to go”?

Tears and anguish are a night-time tradition in the Canaries, at least when Europe’s migrating sailors pull into port every autumn. Descending locust-like on the supermarkets, they buy up crates of beer and bananas, pampers and milk as though supplies everywhere else on Earth had run out. Smart yachts sit ever lower in the water as more and more provisions are stowed. Shopping keeps the sailor’s mind from wandering – a welcome respite when the default setting of so many minds at this stage of November is good honest bowel-churning fear. Nobody speaks the question aloud, but the whispers rising through the jungle of masts and flags are almost deafening: “to go or not to go”?

The Canaries see excuses crafted, one-way flights booked, bunks and not-quite-loved-enough ones quietly abandoned and sad boats left to the mercy of the oily harbour waters. The realisation that the moment of truth has arrived triggers introspection and soul-searching for many a would-be sea-dog. The challenge – the alluring challenge that brought everyone here in the first place – is imminent: see it through or discover a pressing engagement elsewhere?

The draw of the ARC – its attraction and also the reason it accounts for so many sleepless nights in late November – is clear: bear West from these shores and you close the door behind you, committed to chasing the sunrise until the palms, those elegant swaying palms from the dreams of so many years, finally break the horizon for real and you burst Columbus-like into the New World taller, bolder and decidedly thirstier. Or not …

The draw of the ARC – its attraction and also the reason it accounts for so many sleepless nights in late November – is clear: bear West from these shores and you close the door behind you, committed to chasing the sunrise until the palms, those elegant swaying palms from the dreams of so many years, finally break the horizon for real and you burst Columbus-like into the New World taller, bolder and decidedly thirstier. Or not …

Jimmy Cornell, the founder of the ARC, has become a father figure to generations, soothing their fears, raising their sprits and reaffirming (restoring?) their belief that even the most ordinary sailor can cast off here and make it safely to the other side. Jimmy’s encouragement has given countless yachtsmen and women the confidence to spread their wings.

A more wretched jumping-off point than the old Muelle Deportivo de Las Palmas it’s hard to imagine. Managing a whole night’s sleep in this dark, polluted and altogether unloved corner of the commercial port without being launched onto the cabin sole by the constant wash counted as a considerable achievement. There were cockroaches aplenty too, but it’s surprising what a relief it can be to spy a small herd of them roaming the cockpit when the other likely candidate for scuffling noises in the night walks upright and has his sticky fingers set on spiriting away the best of what the crew carefully loaded just a few hours earlier. Manfred Kerstan once bought two televisions for his yacht Albatros just to improve his chances of leaving here with at least one on board!

A more wretched jumping-off point than the old Muelle Deportivo de Las Palmas it’s hard to imagine. Managing a whole night’s sleep in this dark, polluted and altogether unloved corner of the commercial port without being launched onto the cabin sole by the constant wash counted as a considerable achievement. There were cockroaches aplenty too, but it’s surprising what a relief it can be to spy a small herd of them roaming the cockpit when the other likely candidate for scuffling noises in the night walks upright and has his sticky fingers set on spiriting away the best of what the crew carefully loaded just a few hours earlier. Manfred Kerstan once bought two televisions for his yacht Albatros just to improve his chances of leaving here with at least one on board!

Over the 25 years of the ARC, however, things on the waterfront have changed almost beyond recognition. Today’s marina nestles behind protective breakwaters, the polished chrome of its kilometres of gleaming pontoons enjoying 24-hour security, proper lighting and infinitely improved facilities including shipyards and Travelifts, WLAN access to the harbourmaster and the world plus just about every other service imaginable. And, of course, there are bars, bars enough to make sure any itinerant mariner with an urge to earn one more headache before the off has every opportunity to do so.

Jimmy deserves enormous credit for the changes wrought: for his shrewd and tireless lobbying of the big shots in the business and political arenas and his ability to convince them – in fluent Spanish no less – that a smart marina for well-heeled yachtsmen and women on passage would bring far more into island coffers than any number of the package holiday tourists who pay for almost everything before they leave home and consume almost nothing but sunshine and beach space once here.

Jimmy deserves enormous credit for the changes wrought: for his shrewd and tireless lobbying of the big shots in the business and political arenas and his ability to convince them – in fluent Spanish no less – that a smart marina for well-heeled yachtsmen and women on passage would bring far more into island coffers than any number of the package holiday tourists who pay for almost everything before they leave home and consume almost nothing but sunshine and beach space once here.

Jimmy has made some friends for life in the Canaries too in the process and surely nobody but him could have persuaded warships out of the harbour to loose off a few warning shots – real shells that is, not glorified fireworks – to send the fleet on its way.

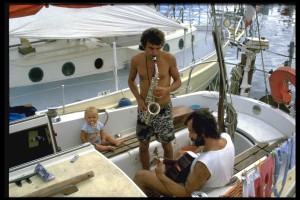

Like Las Palmas, the ARC itself has changed over the last 25 years. Once principally a rally for adventurous families, it has grown into a major event in which families have become a distinct minority. The number of boats may have stayed more or less the same, but the number of names on the entry list leaves at least half the story untold: the average length of the ARC yacht has already reached 50 feet and the number of berths has soared.

Like Las Palmas, the ARC itself has changed over the last 25 years. Once principally a rally for adventurous families, it has grown into a major event in which families have become a distinct minority. The number of boats may have stayed more or less the same, but the number of names on the entry list leaves at least half the story untold: the average length of the ARC yacht has already reached 50 feet and the number of berths has soared.

The now well-established practice of selling berths individually affects the social structure of the event too by subtly shifting the focus. Naturally there are still parts of the marina where family cruisers dominate, not least because the sheer length and beaminess of the troop transporters confines them to other quarters, but if it’s social life, parties and seminars you want, you can be sure of finding them – and a host of other events – here.

It used to be that the whole spirit of the ARC came straight from Jimmy’s genial presence: eloquent, quick with the wry remarks and seemingly omnipresent, he ruled over the event virtually single-handed. Installed in the command centre where the breakwaters met, he had the entire harbour under his control at all times. Jimmy’s word was law and resistance was futile. One hard stare from beneath those bushy eyebrows usually sufficed – and his authority stretched well beyond the furthest mooring.

It used to be that the whole spirit of the ARC came straight from Jimmy’s genial presence: eloquent, quick with the wry remarks and seemingly omnipresent, he ruled over the event virtually single-handed. Installed in the command centre where the breakwaters met, he had the entire harbour under his control at all times. Jimmy’s word was law and resistance was futile. One hard stare from beneath those bushy eyebrows usually sufficed – and his authority stretched well beyond the furthest mooring.

Today this spirit has gone with the wind.

World Cruising has become a tour operator: backed by powerful sponsors, it organises sailing rallies around the world with strict rules, rigorous safety checks and a supporting programme covering essential activities like water fights, brass bands and fancy dress parties as well as informative seminars. And it provides all of this for a fee moderate enough to attract some who would have dared and mastered the passage even without its gentle encouragement.

No sooner does the ARC fleet cast off than another swarm of yachts converges – as if by wild coincidence – from other ports to shadow them across the Atlantic, their crews sleeping a little easier thanks to the comforting thought of safety in numbers. The ARC today thus offers a peculiar variety of flotilla sailing, a virtual flotilla in which the participants, though they soon lose sight of each other on the water, remain joined by their link to the Mother Company and their fellow customers. This notion of a cruise in company on a grand scale engenders confidence, calming the nerves of skippers, crew and their nearest and dearest to the extent that it is now seen as all but guaranteeing a safe passage and a successful arrival in that paradise we cruising sailors have revisited so often in our daydreams, that succulent carrot dangling at the end of the stick we call work. The ARC is of our time: it is encouragement and enablement packaged up to buy.

And then comes the start. Months or years of preparation, a couple of thousand miles at sea to come and yet without a cool head in charge it is all too easy, in the brief melee of departure, to plant an energetic and expensive kiss on one of the other boats. Remarkably the start still always seems to involve a degree of stainless remodelling and gel coat removal (or worse) in the headlong rush to gain a few metres, hit that imaginary line on the very B of the Bang … and be the first to wallow to a halt in one of the holes waiting to ensnare the unwary offshore of the airport.

And then comes the start. Months or years of preparation, a couple of thousand miles at sea to come and yet without a cool head in charge it is all too easy, in the brief melee of departure, to plant an energetic and expensive kiss on one of the other boats. Remarkably the start still always seems to involve a degree of stainless remodelling and gel coat removal (or worse) in the headlong rush to gain a few metres, hit that imaginary line on the very B of the Bang … and be the first to wallow to a halt in one of the holes waiting to ensnare the unwary offshore of the airport.

Peter Foerthmann