OR SHOULD WE CALL IT A “LEARNING OPPORTUNITY”?

400 metres from the finish, the wind went back to bed. Completely and utterly. Would it not have been a beautiful gesture to keep blowing, however gently, for another few minutes and allow Jeremy, out of food after almost 40 weeks at sea and desperately keen for a decent meal, a hot shower and an uninterrupted sleep, to stick his bow across the line and return to civilisation there and then instead of shutting off that very instant and leaving him to drift backwards on his own for another six hours? After all he had surely already faced challenges enough, creeping north from the Azores and across Biscay in unfavourable winds with a broken forestay, provisions running short and fresh water available only via a hand-cranked desalinator.

400 metres from the finish, the wind went back to bed. Completely and utterly. Would it not have been a beautiful gesture to keep blowing, however gently, for another few minutes and allow Jeremy, out of food after almost 40 weeks at sea and desperately keen for a decent meal, a hot shower and an uninterrupted sleep, to stick his bow across the line and return to civilisation there and then instead of shutting off that very instant and leaving him to drift backwards on his own for another six hours? After all he had surely already faced challenges enough, creeping north from the Azores and across Biscay in unfavourable winds with a broken forestay, provisions running short and fresh water available only via a hand-cranked desalinator.

When subsequently asked by Don McIntyre how it felt to have come so close to finishing only to see the line start moving away from him again, Jeremy could have been forgiven for providing a properly colourful response. Instead, paragon of composure that he is, Jeremy just remarked rather drily that meditation had helped him cope with the situation – a response that speaks volumes. As the final entrant remaining on the water, Jeremy represented Don’s last chance to wring another shot of drama from the race, so the six-hour extension in tortuous circumstances may not have been unwelcome in all circles.

Friday the 9th of June 2023 nevertheless turned out to be the last of Oleanna’s 277 days at sea. Late in the afternoon, the elusive line finally broken, Jeremy took a tow in past largely deserted breakwaters to a largely deserted marina where no more than about 50 people waited to welcome him back. The mix of joy and relief on his face suggested he wasn’t bothered and probably hadn’t even noticed. He may never have been more eager in his life to find a shower, a stable bed and some peace and quiet but he remained a sailor visibly in harmony with himself and the world – albeit one who might need a little time to readjust to the pace and pattern of life ashore. Did he miss the attractions of dry land? Not to any significant degree I suspect. None of the many tough challenges he faced over the course of the race put a dent in his sense of humour and he very much gave the impression of being in his natural habitat.

Friday the 9th of June 2023 nevertheless turned out to be the last of Oleanna’s 277 days at sea. Late in the afternoon, the elusive line finally broken, Jeremy took a tow in past largely deserted breakwaters to a largely deserted marina where no more than about 50 people waited to welcome him back. The mix of joy and relief on his face suggested he wasn’t bothered and probably hadn’t even noticed. He may never have been more eager in his life to find a shower, a stable bed and some peace and quiet but he remained a sailor visibly in harmony with himself and the world – albeit one who might need a little time to readjust to the pace and pattern of life ashore. Did he miss the attractions of dry land? Not to any significant degree I suspect. None of the many tough challenges he faced over the course of the race put a dent in his sense of humour and he very much gave the impression of being in his natural habitat.

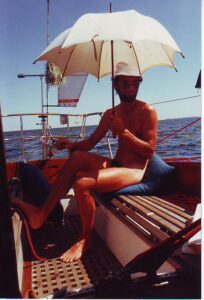

Jeremy (a far leaner version of Jeremy than I have ever seen before) handled Don’s rather uninspiring questions with his usual equanimity, authenticity and politeness. That’s Jeremy. What did Don expect, I wonder, when he asked Jeremy’s opinion of the GGR as an event? Surely of all moments, this was one in which to focus on the sailor and his achievement and experiences, not the organiser and his race! The interview took only a few minutes; Aida captured the mood in 71 photos.

Jeremy (a far leaner version of Jeremy than I have ever seen before) handled Don’s rather uninspiring questions with his usual equanimity, authenticity and politeness. That’s Jeremy. What did Don expect, I wonder, when he asked Jeremy’s opinion of the GGR as an event? Surely of all moments, this was one in which to focus on the sailor and his achievement and experiences, not the organiser and his race! The interview took only a few minutes; Aida captured the mood in 71 photos.

The conclusion of the GGR 2022 marks the end of a tense time for me too even though we had but two Windpilot boats in this edition and, with both skippers very well known to us over a number of years, no chance of a repeat of the unpleasant events of the 2018 race.

Confident as I was in Abhilash and Jeremy, there was still one variable I could do nothing to control: GGR impresario Don McIntyre. I am of course interested first and foremost in how the GGR boats ornament their transom, as self-steering is everything in this event. Don McIntyre obviously understands this too but, with two editions of the race now in the logbook, I am more convinced than ever that his early decision to exploit and monetarise this fact for his own benefit amounts to a critical design flaw at the heart of the GGR concept. It has hung over the event like a dark cloud ever since the first start in 2018 and the consequences for competitors who thought it best, in their eagerness to gain a place on the starting line, to comply with the organiser’s obvious preference in this area have been at times severe. It was the realisation that self-steering problems have now been a constant through two editions of the GGR that led me to the title of this article: DON’S PYRRHIC VICTORY (and the subheading “Or should we call it a ‘learning opportunity'”?

METAMORPHOSIS OF GGR YACHTS

A number of boats changed owner and/or name between the two editions and some had a change of windvane self-steering system. How did the latter affect their performance? Well, Asteria and Puffin both completed the GGR 2018 with a Windpilot system at the controls. Both were then switched to a “Don-compliant” Hydrovane for the GGR 2022. Asteria sank and Puffin was abandoned.

One the other hand, Bayanat and Olleanna both made it all the way around this time with Windpilot after failures with other windvane self-steering systems forced their previous owners to retire from the 2018 race (Philippe Péché’s PRB and Are Wiig’s Olleanna both ended up in Cape Town rather than Les Sables).

I would like to think it may be down to more than just blind chance that all four of these boats enjoyed considerably more success with a Windpilot than without (but then I would, wouldn’t I). Michael Guggenberger’s Nuri made it to the GGR 2022 finish successfully with the Hydrovane system undamaged. Sailing the GGR 2018 as Métier Intérim (Antoine Cousot), the same boat had a Windpilot on the transom and, again, no self-steering failures.

I am especially interested in the circumstances surrounding the loss of Asteria and Puffin, because the particular characteristics of auxiliary rudder systems play a leading role in both stories and I have real concerns about the implications for the safety of our GGR campaigners. I set ou conclusions from the GGR 2018 in my book Windvane Report, which looks at the distinctive features of all the systems on the market paying particular attention to overload protection (both lateral and fore-and-aft) in severe weather events including knockdowns, rollovers and pitchpoling. In summary, it appears the exceptionally large arc through which the pendulum rudder on my Windpilot Pacific can safely travel before hitting something (approximately 270 degrees) probably makes it the best-protected system against overloading in extreme situations. None of the Windpilot systems used across the two editions has suffered any major breakages and none of the skippers has had cause to deploy the replacement system all have carried on board.

It does not seem unreasonable to point this out, especially as it confirms the more technically advanced forms of servo-pendulum system are indeed superior to their more traditional antecedents in bad weather. The Pacific series first went into production almost 40 years ago (1984-2023) and there are many thousands of examples in use all over the oceans of the world, so this is a very welcome (if long-anticipated) result!

It does not seem unreasonable to point this out, especially as it confirms the more technically advanced forms of servo-pendulum system are indeed superior to their more traditional antecedents in bad weather. The Pacific series first went into production almost 40 years ago (1984-2023) and there are many thousands of examples in use all over the oceans of the world, so this is a very welcome (if long-anticipated) result!

HEAVY WEATHER AND THE JORDAN SERIES DROGUE (JSD)

Sailing the GGR 2018, Susie Goodall found that her Monitor self-steering system made it more difficult to use her Jordan Series Drogue – or vice versa. The failure of the JSD played a large part in the devastating pitchpole that ended her participation. Difficulties deploying the JSD around the Hydrovane then caused big problems for Puffin in the GGR 2022. Approaching Cape Horn, a warp from the drogue became fouled on the Hydrovane rudder and snapped it in half. Having had to stop to effect repairs, the skipper was unwilling to risk the JSD again in the subsequent South Atlantic storm that eventually forced him to abandon ship. Will the organiser change anything in his approach for future editions in light of these dreadful events or will he continue to leave entrants entirely to their own devices when it comes to storm tactics?

Sailing the GGR 2018, Susie Goodall found that her Monitor self-steering system made it more difficult to use her Jordan Series Drogue – or vice versa. The failure of the JSD played a large part in the devastating pitchpole that ended her participation. Difficulties deploying the JSD around the Hydrovane then caused big problems for Puffin in the GGR 2022. Approaching Cape Horn, a warp from the drogue became fouled on the Hydrovane rudder and snapped it in half. Having had to stop to effect repairs, the skipper was unwilling to risk the JSD again in the subsequent South Atlantic storm that eventually forced him to abandon ship. Will the organiser change anything in his approach for future editions in light of these dreadful events or will he continue to leave entrants entirely to their own devices when it comes to storm tactics?

Why is this so important? Today, the JSD can be regarded as the state-of-the-art response to boat-threatening sea conditions. Once deployed, it will reliably keep the boat stern-on to wind and waves, reducing the hull surface area exposed to confused breaking seas and granting the crew a little respite. Using a JSD in combination with a windvane self-steering system can be dangerous, however, if the self-steering rudder cannot be retrieved from the water before deploying the drogue. Moving the rudder out of harm’s way is essential to avoid incidents like the one that befell Puffin.

Susanne Huber-Curphey, who credits the JSD with keeping her in one piece through several extreme storms experienced over the course of more than 300,000 nautical miles exploring aboard Nehaj, is absolutely clear on this point. More of Susanne’s advice on surviving extreme conditions can be found in the latest edition of Adlard Coles’ classic reference work Heavy Weather Sailing.

JSD USE WITH DIFFERENT TYPES OF WINDVANE SELF-STEERING

Using a JSD with an auxiliary rudder system (Hydrovane, Windpilot Pacific Plus) is inherently problematic because of the risk that a sudden pull on the JSD system will cause it to damage the auxiliary rudder, as happened to Puffin off Cape Horn, or rip it off completely.

Using a JSD with an auxiliary rudder system (Hydrovane, Windpilot Pacific Plus) is inherently problematic because of the risk that a sudden pull on the JSD system will cause it to damage the auxiliary rudder, as happened to Puffin off Cape Horn, or rip it off completely.

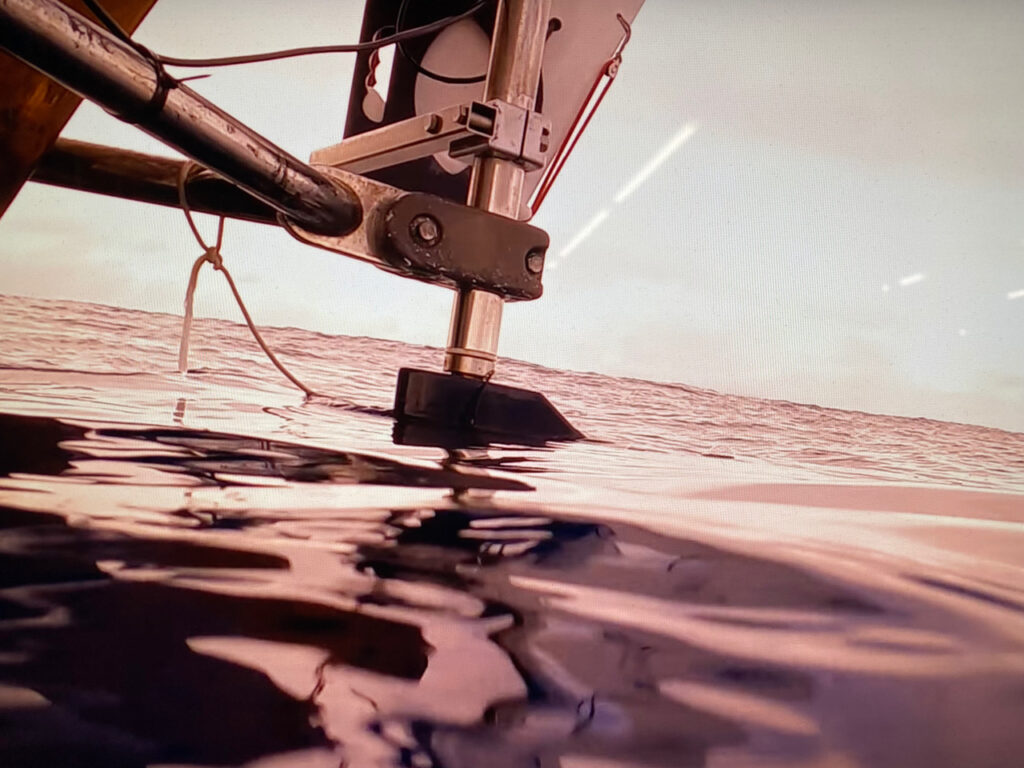

Using a drogue with a servo-pendulum system poses no such risk provided that the pendulum rudder itself is taken out of service and removed or lifted up out of the water before the drogue is deployed. Each servo-pendulum system has a different method for doing this.

– Aries: drop the pendulum rudder out and remove it aft, which works even under load

– Monitor: release the locking mechanism on the rudder shaft (the rudder does remain vulnerable, as Susie Goodall discovered in the GGR 2018, because it cannot be removed completely)

– Windpilot Pacific: release the rudder clamp so that the bottom end of the blade pops up aft and then swing the whole mechanism up out of the water to one side (lift-up) so that it is completely out of the way of the danger zone created by the bridle, which is robustly attached on both corners at the stern.

Mark van den Weg, who has made some simple upgrades to the Pacific on his yacht Jonathan to help it and his JSD share the transom more amicably, recently aired to me some definitive views on storm tactics borne of his own extensive experience:

Mark van den Weg, who has made some simple upgrades to the Pacific on his yacht Jonathan to help it and his JSD share the transom more amicably, recently aired to me some definitive views on storm tactics borne of his own extensive experience:

Hi Peter,

Some thoughts on the choice of windsteering systemsIf your boat needs an extra rudder to steer the boat there can be several considerations that don’t make sense.

• There is something wrong with the steering system on the boat.

• You are driving the boat way harder then the designer intended.

• Since Abilash came in as a close second it makes clear that a Windpilot Pacific is a very capable system even if you are racing.

I find it very weird that when you prepare for the GGR and you intend to use a Jordan Series drogue and a Hydrovane that you do not make any arrangements so that the line for the drogue cannot get entangled with the Hydrovane rudder. It would be very difficult to do so with a Hydrovane and it would create another weak point in the system. Even if you could swing up the Hydrovane rudder the drogue can still do considerable damage to the system and it’s transom supports. Ian Herbert of Puffin did not want to deploy the drogue when the weather deteriorated because he knew by experience that it would snap off the rudder of the Hydrovane as happened to him just before reaching Cape Horn. With an Aries and a Windpilot you can swing up the pendulum and thus reduce the risk of damage to the system almost to zero. Now it might be difficult to lift the pendulum on a Windpilot when the boat has some speed.

Therefore we installed the quick release as in the picture we send you earlier. It is much the same as a quick release for a wheel on a bicycle. The one we installed we found online and is made from stainless steel. I drilled a 6 mm hole in the handle and there is a small line going to the push-pit. If I want to release the pendulum we just have to pull the line. ( If it is hard to release, with the windvane I swing the pendulum up. Then put the little line around a cleat and swing the pendulum back again and the quick release will open). The pendulum rudder swings up backwards and then it’s easy to lift it out of the water and harms have gone away. (We also use it when kelp gets stuck on the pendulum)

The KISS principle should be very high on the list of any GGR participant. A Hydrovane has many fiddly parts and is not easy to work on. Partly because the housing restricts access and at sea it would be easy to loose parts over the side. The winner of the GGR had a complete second system on board. Simon Curwen would easily have won the GGR if he had not just taking the spare parts kit but a complete second system. Not something you would do when you go cruising.

On our boat Jonathan we recently finished our Southern Ocean circumnavigation although we took our time to visit many beautiful and remote locations we more or less sailed the same waters as the GGR. We did not need any repairs to the Windpilot all those miles. Now maybe a few simple bush bearings could be replaced and that’s it. On our Koopmans 48 we have a drag link steering system and we can release the wheel in the cockpit. On the aft deck there is a little helm for the Windpilot that would also serve as an emergency tiller. This tiller is also connected to the rudder by a drag link. We do not have the chain plates bolted on the hull like you see often for the use of a Jordan Series drogue. We have oversized clamps welded and bolted to the heavy aluminum toe rail. But in all our sailing we only used them to try out the Jordan’s Series drogue. So far we never really needed the drogue, the Windpilot did the job, no matter which or what.

Cheers Mark, SV Jonathan

WHY, WHY, WHY?

Now, it might seem odd at first to find an investigation of the safety implications of using windvane self-steering (WSS) systems in the GGR on the blog of a windvane self-steering system manufacturer, but I believe the question needs to be asked and I see no sign of the organiser addressing the incidents involving WSS that have occurred during his event with anything like the necessary thoroughness or objectivity. The matter is of course potentially a rather sensitive one given the implications for the event’s main sponsor – which brings us back to the baked-in design flaw I mentioned earlier.

We do need an objective examination of the situation nevertheless in the interests of the safety of future GGR participants. I question the logic of always leaving critical safety issues to the participant’s sole discretion when the organiser has a treasure trove of empirical evidence at his disposal. Why not collate these lessons learned the hard way and share them with the next generation? We are after all talking about information that could very well help future GGR sailors avoid some of the awful situations that have jeopardised safety in the first two editions. Robin Knox-Johnston’s report into the frequency of storms after the GGR 2018 paid relatively little attention to the background of the events he investigated.

The man at the keyboard typing these words has built all the different types of WSS over the last 47 years, including thousands of auxiliary and double rudder systems. Knowing what I do based on all this practical experience, I was actively advising sailors heading to high latitudes against auxiliary and double rudder systems – on safety grounds – even before the GGR 2018. The reasons are not complicated:

The man at the keyboard typing these words has built all the different types of WSS over the last 47 years, including thousands of auxiliary and double rudder systems. Knowing what I do based on all this practical experience, I was actively advising sailors heading to high latitudes against auxiliary and double rudder systems – on safety grounds – even before the GGR 2018. The reasons are not complicated:

– Auxiliary/double rudder systems can place enormous loads on the transom in extreme sea conditions, making the strength not just of the mounting components but the boat itself a key issue.

– Auxiliary/double rudder systems are very exposed to flotsam.

– It is very difficult indeed to repair or replace an auxiliary/double rudder system on the open sea.

The GGR rules require participants to carry an emergency rudder, a requirement that can be satisfied to the organiser’s complete satisfaction by fitting a Hydrovane-brand auxiliary rudder self-steering system. Looking back over the two GGR events that have now taken place, it would appear that this apparent advantage (from the sailor’s perspective) of the auxiliary rudder system really needs to be balanced against the safety shortcomings this same system has now revealed to the world. An emergency rudder could well come in handy one day, but if heavy weather is assured, is it worth compromising on heavy weather safety in exchange for the theoretical gain of an easy emergency steering solution? Measuring the number of boats to have been knocked out of the event by WSS issues in severe weather (a fair few) against the number to have had to fall back on emergency steering (none so far), it is difficult not to question the organiser’s motivation in making such a priority of the emergency steering issue.

REDUNDANCY

Reliable self-steering is vital for any solo sailor. Participants in the retro-themed GGR do not have the option of an electric autopilot for redundancy (at least they do, but only if they are prepared to accept relegation to the Chichester Class if they use it) and are therefore completely dependent on their WSS, which makes WSS issues a wonderful source of recurrent drama for the organiser’s race reports (I’m not suggesting he would have seen that coming, but I don’t suppose he minds). The problem is that with WSS being so critical, even something as apparently routine as a safety tube breaking under excessive load in exactly the manner it was designed to can trigger an emergency (as in the case of Are Wiig). Is that a price worth paying for the drama? Is it really proportionate for any hiccup with the WSS potentially to put the safety of boat and skipper in jeopardy? We can see now that this does actually happen, over and over, because the rules pitch safety (which would indicate breaking out the autopilot while repairing the WSS) against the competitive instinct (nobody starts the race aiming to finish in the Chichester Class). The conflict is clear.

The GGR 2018 highlighted the limitations of all WSS (overload protection).

It turns out there are many different technical failure modes for a windvane self-steering system under GGR conditions, many of which the organiser, in his defence, cannot have been expected to anticipate when he was confecting his rules. That was most assuredly not the case by the time the GGR 2022 started. All the incidents of the first event had been thoroughly investigated and properly explained in the interim and the implications were obvious. Regrettably the organiser did not feel the need to adjust his rules in response to this new knowledge for the 2022 edition. Had he done so, he might not now be looking back on what really looks like a Pyrrhic victory: yes, he had twelve Hydrovane-equipped boats on the start line, but a large proportion of them went on to suffer conspicuous failures. Will this new raft of evidence trigger a rethink? It appears the organiser has chosen a different course and that, rather than accepting the systemic problem, he prefers to apportion blame on a case-by-case basis to:

– the sailors themselves (Damien Guillot)

– collision (Tapio Lehtinen)

– erroneous decision-making (Ian Herbert-Jones)

One advantage of there having been so many systems deployed is that we now have enough information to compare the details of different experiences and draw meaningful conclusions from the results. This de-facto field test could in fact be a real boon if the organiser and the manufacturers are prepared to embrace the opportunity it presents. The components of concern are now obvious. What appears to be the most critical of them is the “H-bracket” used to install almost all of the Hydrovane systems used in the GGR. This element of the mounting system has been implicated in

One advantage of there having been so many systems deployed is that we now have enough information to compare the details of different experiences and draw meaningful conclusions from the results. This de-facto field test could in fact be a real boon if the organiser and the manufacturers are prepared to embrace the opportunity it presents. The components of concern are now obvious. What appears to be the most critical of them is the “H-bracket” used to install almost all of the Hydrovane systems used in the GGR. This element of the mounting system has been implicated in

– the loss of Asteria,

– the inadequate strength of the upper mounting on Jean Luc van den Heede’s Matmut,

– the inadequate strength of the upper mounting on Simon Curwen’s Clara.

Having identified the H-bracket as a potential weakness in good time, Kirsten Neuschäfer eliminated the danger by integrating the problem component into a custom stainless-steel fitting just above the waterline. Having listened to her fascinating podcast, I can confirm that this was just one of the many ways in which this very smart sailor made sure the technology she had on board worked to her advantage rather than undermining her efforts. My friend Australian Mike Smith suggests another interesting factor that may also have helped to keep Kirsten out of self-steering trouble:

Having identified the H-bracket as a potential weakness in good time, Kirsten Neuschäfer eliminated the danger by integrating the problem component into a custom stainless-steel fitting just above the waterline. Having listened to her fascinating podcast, I can confirm that this was just one of the many ways in which this very smart sailor made sure the technology she had on board worked to her advantage rather than undermining her efforts. My friend Australian Mike Smith suggests another interesting factor that may also have helped to keep Kirsten out of self-steering trouble:

Kirsten, an excellent seaman, no doubt attended to the Hydrovane every day. Lady skippers generally tend to pay attention to trim, preferring a lighter helm and less muscle. I expect the Hydrovane did not work too hard on Minnehaha.

Also of particular importance are the shear pins, because the auxiliary rudder can be lost altogether if they wear faster than anticipated or fail. Several skippers have addressed this issue by running an additional vertical line from the top of the rudder to the boat to ensure that if a shear pin does give up the ghost, the rudder assembly does not head straight for the deep. A stitch in time…

CLOSER TO HOME

It would of course be remiss of me to talk about investigating WSS incidents without reporting on what happened with my own products. Stories cropped up now and again both on the organiser’s FB page and in international press reports concerning problems Abhilash was supposedly having with his Windpilot. These will all have originated with the organiser – and his conflict of interests when discussing WSS not made by his sponsor has been well-publicised. He though remains the main – and often sole – source of material for the press while the event is in progress so what he says tends to be what readers end up being given to read: with Copy & Paste “journalism” being quick, easy and cheap, we should hardly be surprised to find most sailing news outlets around the world serving up essentially the same fodder. Nor, I suppose, should it surprise us if readers are presented with purported technical facts that don’t quite stand up to closer scrutiny. Journalists have pages to fill, website traffic to generate and glossy magazines to pad, all on an unforgiving schedule and budget: no wonder conveniently packaged news tidbits delivered ready for use complete with sparkling photos so often trump the urge to conduct expensive, time-consuming independent research.

Unfortunately there are losers in this game as well as the obvious winners. It is hard to imagine a more effective way to spread subjective comments that cast a particular product in an unfavourable light and when press reports are full of talk about Abhilash’s apparent problems with his Windpilot and the same message is echoed in a multitude of international online media outlets, brand damage is inevitable wherever the truth may lie. The effect is exacerbated by the almost total failure, intentional or otherwise, of these various mouthpieces and multipliers to make any attempt to clarify the causes or consequences of the stories they are reporting – or even to verify if they are at all accurate. Having said all of that, I perhaps should not be surprised either when a “journalist” cannot even manage to type the name of my brand correctly, but it has not been “Wind Pilot” at any time in the last half-century – and these things matter when a Google search is everyone’s first port of call. Surely Yachting Monthly ought to know better:

Across the Indian Ocean, Abhilash Tomy remained in third place, but began experiencing problems with his Wind Pilot self-steering system, replacing for blade in the servo rudder

Obviously these half-truths are bad for my brand. The question is how did they make it into print and is it right that this false impression is allowed to persist? I also wonder whether tactics of this nature are such a good idea when the real target readership is as knowledgeable and well-informed as it is. The collateral damage of disseminating such inaccuracies should not be underestimated. There are more immediate consequences of spreading false news too, not least competitors’ family and friends. Abhilash’s wife Urmimala e-mailed me the following at one point during the GGR 2022, for example:

„Peter, I am so anxious, can he fix it or is all over?“

Peter Mott asked me whether it might not be a good idea to produce a system could “Southern” because, as he saw it,

We live in a world where branding is king. A product named Southern with messaging around it being purpose built for the rigours of the southern ocean should get some traction.

What really happened?

Abhilash did his best to get his boat airborne without foils. Average speeds approaching 6.8 knots and 180-nautical mile days should give some idea of the enormous pressure Abhilash placed on the tiller – and himself. Performance like that from a boat like Bayanat means carrying plenty of sail even in heavy weather. Pushing his Pacific that hard on the way to Cape Horn caused it to chew through three rudder blades and a number of windvanes. It just wore them out.

The mechanicals of the system saw Abhilash to the finish though, even through 10,000 nautical miles with the shaft of a Fortress anchor in place of the usual finely balanced lightweight rudder blade. Needs must!

The mechanicals of the system saw Abhilash to the finish though, even through 10,000 nautical miles with the shaft of a Fortress anchor in place of the usual finely balanced lightweight rudder blade. Needs must!

There is one other thing I ought to mention here. A few days after purchasing the ex-PRB from Philippe Péché in March 2022, Abhilash and Dick Koopmans moved the boat up to Den Oever. The weather was fine, minds had time to wander and at some point on the journey the idea was apparently hatched to fit Bayanat with two Pacific systems in series (one behind the other) just in case. When I saw the outcome of this idea for myself on visiting Den Oever I was horrified.

Sitting on the transom was a double bracket intended to accommodate two Pacific systems a whole 3 cm apart so that one could take over if the other failed on duty. I explained the risks as I saw them and in due course the rear part of the bracket disappeared. I hope Dick Koopmans will feel able to forgive me now for being so forceful on the subject. He certainly did not appreciate my insistence at the time!

Sitting on the transom was a double bracket intended to accommodate two Pacific systems a whole 3 cm apart so that one could take over if the other failed on duty. I explained the risks as I saw them and in due course the rear part of the bracket disappeared. I hope Dick Koopmans will feel able to forgive me now for being so forceful on the subject. He certainly did not appreciate my insistence at the time!

The system of routing the steering lines via tubular extensions protruding over the stern trialled in Den Oever was also abandoned after several breakages in favour of a more conventional arrangement straight from the crossbar to the transom. Abhilash did still take a complete spare Pacific system with him, but it saw no action and was returned to Hamburg a few days after he finished.

The system of routing the steering lines via tubular extensions protruding over the stern trialled in Den Oever was also abandoned after several breakages in favour of a more conventional arrangement straight from the crossbar to the transom. Abhilash did still take a complete spare Pacific system with him, but it saw no action and was returned to Hamburg a few days after he finished.

Feedback from Abhilash, 2 May 2023:

Feedback from Abhilash, 2 May 2023:

Hello Peter

I couldn’t have finished GGR without windpilot.

So a big thank youAbhilash

Feedback from Jeremy. 12 June 2023:

Feedback from Jeremy. 12 June 2023:

:

Hi Peter

Overall, I thoroughly enjoyed the circumnavigation and especially as I had such a capable helm driving my boat perfectly, 24 hours a day!Your Windpilot Pacific is an incredible piece of equipment. The only damage I suffered to it was two snapped plywood vanes, both taken out by exceptionally large waves boarding from behind. But with plenty of spares, I was always back at full operating level within minutes.

All the very best,

Jeremy

WINDVANE SELF-STEERING SYSTEMS IN THE GGR – STATISTICS

GGR 2018 – Systems on the start line

2 Aries,

3 Beaufort

7 Hydrovane

3 Monitor

5 Windpilot

Finishers

1. Jean-Luc van den Heede, Hydrovane

2. Mark Slats, Aries

3. Uku Randmaa, Hydrovane, Monitor

4. Istvan Kopar, Windpilot

5. Tapio Lehtinen, Windpilot

System failures and retirements

Nabil Amra, Beaufort, Bruch der WSA

Francesco Cappelletti, Beaufort, Bruch der WSA

Philippe Péché, Beaufort, Bruch der WSA

Are Wiig, Monitor, mehrfacher Bruch Überlastungsschutz, Kenterung

Susie Goodall, Monitor, mehrfacher Bruch Überlastungsschutz, Interaktion zwischen JSD und WSA, Überkopf Kenterung, Aufgabe des Schiffes.

Windpilot systems still intact and functional at finish or on retirement/abandonment

Abhilash Tomy, mehrere Kenterungen, Verlust beider Masten, Untergang

Istvan Kopar, zwölf Stürme >50kn, drei Kenterungen Ankunft im Ziel als 4.

Tapio Lehtinen, Ankunft im Ziel als 5.

Antoine Cousot, Abbruch in Rio de Janeiro aus persönlichen Gründen

Igor Zaretskiy, Abbruch in Freemantle Au aus gesundheitlichen Gründen

Alle Windpilot Segler waren mit einem kompletten System zur Redundanz ausgerüstet – sie blieben sämtlich unbenutzt.

GGR 2022 – Systems on the start line

2 Aries

12 Hydrovane

2 Windpilot

Finishers

1. Kirsten Neuschafer, Hydrovane

2. Abhilash Tomy, Windpilot

3. Michael Guggenberger, Hydrovane

Simon Curwhen, Hydrovane Chichester Class

Jeremy Bagshaw, Windpilot Chichester Class

System failures and retirements s

Damien Guillou, Hydrovane mehrfacher Ruderbruch, Aufgabe

Ian Herbert-Jones, Hydrovane, Ruderbruch durch Interaktion JSD WSA, Durchkenterung, Aufgabe

Tapio Lehtinen, Hydrovane, Untergang des Schiffes

Pat Lawless, Aries Lagerschaden, Aufgabe

Simon Curwhen, Hydrovane, Bruch des Windfahnensupports, Zieldurchgang in Chichester Class

Boats that changed WSS between 2018 and 2022

PRB, Phillipe Péché, Beaufort = Bayanat, Abhilash Tomy, Windpilot

Métier Intérim, Antoine Cousot, Windpilot = Nuri, Michael Guggenberger, Hydrovane

Olleanna, Are Wiig, Monitor = Olleanna, Jeremy Bagshaw, Windpilot

Puffin, Istvan Kopar, Windpilot = Puffin, Ian Herbert-Jones, Hydrovane

Asteria, Tapio Lehtinen, Windpilot =A steria, Tapio Lehtinen, Hydrovane

NUMBER GAMES

I am not one for twisting or torturing the statistics, but I do like the following little number game:

– Approximately 20% of starters (7 of 34) across the two GGR editions so far had a Windpilot steering slave

– Precisely 40% of finishers (4 of 10) across the two GGR editions so far had a Windpilot steering slave

Does that count as splitting hairs? It put a smile on my face in any case. Perhaps you could tell…

Peter Foerthmann

Hamburg, 14 June 2023

Hello Peter,

I won’t say I have a lot of experience with mechanical self-steering but having sailed 40,000 miles with the Winpilot, I say I am quite impressed with its performance. During the last GGR, any other self-steering could have caused me to retire. It was thanks to Windpilot that I made it to the finish.

If you look at the failures in my Windpilot, you will notice that while the attachments failed, the main unit remained intact. These attachments, like the vane and rudder blade, are easily replaceable – it did not take me more than 5 mins to replace them even in very bad sea conditions. I did run out of spares probably because I did not cater enough for the length of the voyage. The damage to the rudder blades could be because the Windpilot was installed too low, or maybe because I was driving the boat too hard.

In short, I am in awe of Windpilot and it would be my only recommendation. If I had to do a GGR again, I won’t do it without a Windpilot.