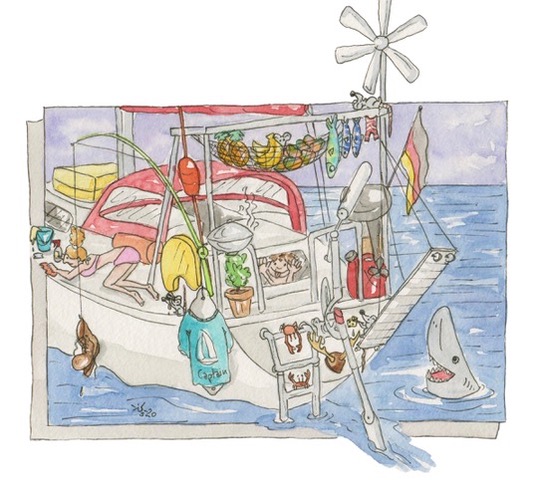

SV Jöke, german built glassfibre Phantom38 left her homeport Grossenbrode some time in 1999 heading South via Dutch, Belgian and French inner waterways to arrive in Marseille some months later.

SV Jöke, german built glassfibre Phantom38 left her homeport Grossenbrode some time in 1999 heading South via Dutch, Belgian and French inner waterways to arrive in Marseille some months later.

Raising the mast to head down the french and Spanish coast and extensively cruising mediteranien waters in 2000 and heading towards Gibraltar and the Canaries in November. Trade winds blow them to warmer waters to arrive in Trinidad at the end of the year 2000.

Raising the mast to head down the french and Spanish coast and extensively cruising mediteranien waters in 2000 and heading towards Gibraltar and the Canaries in November. Trade winds blow them to warmer waters to arrive in Trinidad at the end of the year 2000.

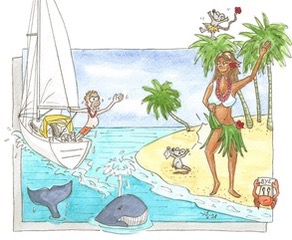

The Caribbean waters were their home for another year passing the Panama Canal in 2002 to head further West towards Marquesas, Tuamotus, Morea,,Raiatea ,Tahaa, Bora-Bora to Aitutaki(Cook-Islands.

The Caribbean waters were their home for another year passing the Panama Canal in 2002 to head further West towards Marquesas, Tuamotus, Morea,,Raiatea ,Tahaa, Bora-Bora to Aitutaki(Cook-Islands.

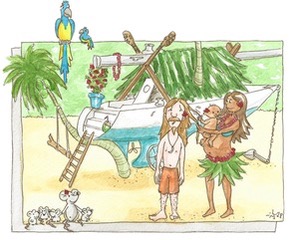

End october they got lost of their rigg on their way to New Zealand, having to return under engine back to Nuku´alofa. It turned out to be impossible to get a new mast at this remote place so they decided to ship their boat as deckload on a containership to Aucjkland NZ. After fixing any problems they started towards Tonga, Samoa, Wallis and Fidji and returned back to NZ the same year.

End october they got lost of their rigg on their way to New Zealand, having to return under engine back to Nuku´alofa. It turned out to be impossible to get a new mast at this remote place so they decided to ship their boat as deckload on a containership to Aucjkland NZ. After fixing any problems they started towards Tonga, Samoa, Wallis and Fidji and returned back to NZ the same year.

They spent another year to pass the Great Barrier reef, Malaysian archipelagos to Langkawi to proceed for Thailand in 2004 where they arrive in Phuket safely.

They spent another year to pass the Great Barrier reef, Malaysian archipelagos to Langkawi to proceed for Thailand in 2004 where they arrive in Phuket safely.

It was just one day after their departure from Phuket when the big Tsunami ruined the coastline of Thailand bringing death for thousands of people. They hardly realized the tsunami because they were at sea.

It was just one day after their departure from Phuket when the big Tsunami ruined the coastline of Thailand bringing death for thousands of people. They hardly realized the tsunami because they were at sea.

After heavy collisison with heavy tree trunks their glassfibre boat took constant water requesting to care for emptiing in a regular way. ON top of this the rudder sustained substancial damage too.

After heavy collisison with heavy tree trunks their glassfibre boat took constant water requesting to care for emptiing in a regular way. ON top of this the rudder sustained substancial damage too.

They went upthe Red Sea in a strong breeze on the nose and tacked the Med from East to West until their arrival in their homeport by end of 2005.

They went upthe Red Sea in a strong breeze on the nose and tacked the Med from East to West until their arrival in their homeport by end of 2005.

SV Jöke, Edith+Michael Zahn GER

What ever happened to boat building? Part 2

If the lively response to the first part of this blog on the German internet forums is anything to go by, this matter may be even more controversial than I suspected: the hornets nest has been stirred, sensitivities have been pricked and unsettled sailors are taking to their keyboards to explain and defend their views and decisions. I would say that one could write heavy books on the subject of these deliberations, but as it happens, most of these books – presenting a variety of perspectives – are already out there.

My take on these complex issues is just that: my take. My expertise lies in self-steering and in helping yachtsman and yachtswomen gain a little respite from the tiller or wheel at sea. I do not claim to have eaten the tree of knowledge leaves, bark, beetles and all! The fact that after several decades in the business and dozens of boats of my own, I find my conversations with a global sailing community increasingly focusing on boats as such rather than ‘just’ the choice of windvane, has helped to keep my job stimulating and has led me in the process to develop a particular point of view.

I believe proper consideration of these ideas based on a rigorous investigation of whether modern is always better could trigger – or at least sow the seeds of – a seismic shift in the way some sailors think about boats. Trying to phrase the arguments involved in simple black and white terms serves no purpose in the same way that no one material can always be the right choice for every boat: just as GRP has its osmosis, aluminium its electrolysis and welded steel its rust, so the plank has its worm. While we have to make a decision, we know that compromise is the real name of the game.

I believe proper consideration of these ideas based on a rigorous investigation of whether modern is always better could trigger – or at least sow the seeds of – a seismic shift in the way some sailors think about boats. Trying to phrase the arguments involved in simple black and white terms serves no purpose in the same way that no one material can always be the right choice for every boat: just as GRP has its osmosis, aluminium its electrolysis and welded steel its rust, so the plank has its worm. While we have to make a decision, we know that compromise is the real name of the game.

Some compromises are better than others, however, and what better way to start an exploration of their relative advantages and disadvantages than with the observations of a certain grey-haired character who, though his age might suggest a rather conservative angle, derives his opinions directly from experience and careful reasoning rather than dogma and stubbornness. Knowledge is a valuable commodity and one it’s hard to have too much of when looking for a new home on the seas.

Some compromises are better than others, however, and what better way to start an exploration of their relative advantages and disadvantages than with the observations of a certain grey-haired character who, though his age might suggest a rather conservative angle, derives his opinions directly from experience and careful reasoning rather than dogma and stubbornness. Knowledge is a valuable commodity and one it’s hard to have too much of when looking for a new home on the seas.

Although the ideas discussed here relate first and foremost to the yacht intended for longer voyages, it cannot do any harm to reflect on them and how they might apply whatever you have in mind. Sailors are dreamers and their dreams – irrespective of whether they ever come to fruition – almost always revolve around open water and distant islands and it consequently makes sense to consider how the picture may have changed over the years in terms of the quality, robustness and price of the great proliferation of production yachts in which we are now invited to trust. Lucky indeed the sailor who manages to plot a smooth passage through these treacherous waters and find a boat that lives up to expectations even after the trials of long-term use.

Much of the first part of this blog concentrated on the impact of changes in boat building methods, industrialization and value-added considerations in large-scale GRP production on concepts of and approaches to hull construction. Today’s production GRP yachts have become far removed from the traditional understanding of what a hull should be and how it acquires its strength. Traditional structures are not necessarily the only solution, but the sense of security their solidity conveys is certainly a nice feeling.

I believe that boats were built better in the past essentially because the methods then employed produced a more robust vessel. And in those days hull, keel and rudder formed a single strong unit, which is always a plus in my eyes. The hull of the typical modern production GRP yacht (I will look at metal hulls another time) consists of just a shell. Keels are manufactured separately and then bolted on, which is both practical – from the manufacturer’s perspective at least – and reduces costs. The implications of the shell approach for bonds, joins, seaworthiness and endurance are widely understood.

It is no accident that modern underwater shapes always include bolt-on extremities in place of the traditional V-form forefoot, guarantor of a smooth ride through waves, good seakeeping and relative peace and quiet down below. Today speed often seems to be the only element of performance that counts. The gung-ho yachtsman can imagine nothing worse than being passed to lee by a bathtub and inherent strength is the asset many seem willing to sacrifice – at times apparently without even beginning to consider the consequences – on the altar of vanity. Why else would it be that more and more offshore events, even those organised primarily for cruisers, are making it mandatory for participants to carry an emergency rudder in order to spare the rescue helicopter the need to launch every time a steering cable jumps off a block?

It is no accident that modern underwater shapes always include bolt-on extremities in place of the traditional V-form forefoot, guarantor of a smooth ride through waves, good seakeeping and relative peace and quiet down below. Today speed often seems to be the only element of performance that counts. The gung-ho yachtsman can imagine nothing worse than being passed to lee by a bathtub and inherent strength is the asset many seem willing to sacrifice – at times apparently without even beginning to consider the consequences – on the altar of vanity. Why else would it be that more and more offshore events, even those organised primarily for cruisers, are making it mandatory for participants to carry an emergency rudder in order to spare the rescue helicopter the need to launch every time a steering cable jumps off a block?

A quick glance at the spacing of the rudder bearings and the leverage that can be exerted on them in most modern designs should provide more than enough material for seafaring nightmares. A spade rudder is certainly efficient in form and effect, but it also makes a tremendous lever and experience suggests the force applied at the bottom at times exceeds the strength of the mounting structure at the top. Not everyone can walk on water and those of us who can’t might do well to avoid knowingly putting ourselves in this situation rather than just trusting the sat phone, EPIRB and shortwave radio to buy us a second bite at the cherry.

A quick glance at the spacing of the rudder bearings and the leverage that can be exerted on them in most modern designs should provide more than enough material for seafaring nightmares. A spade rudder is certainly efficient in form and effect, but it also makes a tremendous lever and experience suggests the force applied at the bottom at times exceeds the strength of the mounting structure at the top. Not everyone can walk on water and those of us who can’t might do well to avoid knowingly putting ourselves in this situation rather than just trusting the sat phone, EPIRB and shortwave radio to buy us a second bite at the cherry.

One Kiwi professional delivery skipper is said to have “worn out” several balanced rudders in the course of taking a European production yacht home to New Zealand. Stories of problems with keels and rudders fill an increasing proportion of the nautical press – although, since they tend to affect solo sailors with the necessary wit to find their own way home, they seldom make headlines outside of the sphere of sailing.

Performance (insofar as it is confused with speed) also has another dark side of which anyone who values the chance to sleep in peace at sea ought to be aware. The number of sailors quickly and quietly trading in their fast rides for better all-around offshore performers is rising rapidly. One seafaring family recently sold their brand new yacht in a hurry at the end of its first bash across the Atlantic, preferring instead to continue their planned trip around the world with a 40-year old classic. While expensive in cash terms, their decision has proven to be the right one and they remain very happy with their replacement to this day

Others have been less fortunate.

Swiss circumnavigator Thomas Jucker puts it very succinctly: “Sailing to New Zealand around the Cape of Good Hope in a lightweight boat is actually not particularly difficult – but it isn’t much fun either.” Jucker currently sails a Bristol Channel cutter. .

.

Just anecdotes? Of course, but there are plenty more where they came from and they tell a consistent story – a story even ordinary sailors who do not spend their whole life at sea would do well to heed if they really want to be able to trust in their boat. The open ocean, of course, has no monopoly on uncomfortable conditions: the combination of strong winds, powerful currents and prominent landforms can put yachts to the test even close to home.

When every week brings new models, glowing test reports and more slick marketing to match and when each successive development seems intended only to make us forget what has gone before, it takes a stoical composure to read between the lines and seek out the real purpose of this spiral of gloss. We can be certain, however, that new does not automatically equal better. Older boats still making their way under sail have proved they can last the distance: novelty in and of itself is no reason suddenly to consign them to the yacht cemetery!

That, at least, is the conclusion so far of

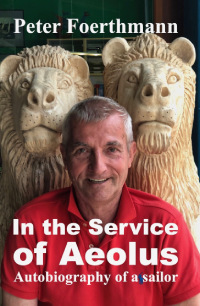

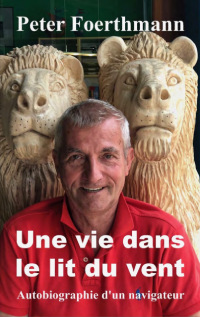

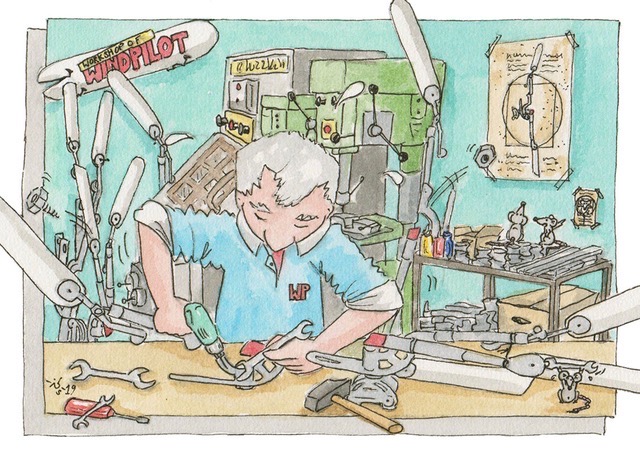

Peter Foerthmann

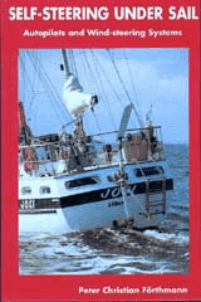

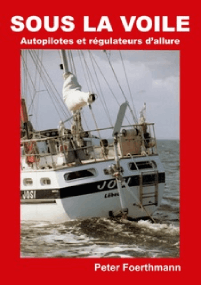

Windpilot – global micro market leader for windvanes

Prof. Dr. Bernd Venohr of the EMF Institute at the Berlin School of Economics

Prof. Dr. Bernd Venohr of the EMF Institute at the Berlin School of Economics

The characteristic features of global market leaders

Germany is the global market leader in global market leaders according to a new book published at the end of January (“Lexikon der deutschen Weltmarktführer” – encyclopaedia of German market leaders). The book’s co-editor Bernd Venohr marked the launch with an interview for German financial and business newspaper Handelsblatt in which he discussed a range of issues including the diversity of the companies qualifying as market leaders, the threats they face and the speed at which China is closing the gap. An excerpt from the interview appears below:

“Handelsblatt: Mr. Venohr, exactly how broad is the spectrum of German market leaders?

Bernd Venohr: I have details of 1,500 companies in my database. Most of them are small and midsize industrial companies and more than half made it into our new encyclopaedia of German market leaders. They range in size from two-person operation Windpilot, which manufactures self-steering systems for sailing boats, to Volkswagen, Europe’s biggest carmaker. I suspect that there are more than 1000 micro world market leaders on top of this, but it is very difficult to gain an accurate picture at this level as they often serve very small niches.”

From: Handelsblatt, January 24, 2011

The full interview – in German – appears here

And here’s another relevant excerpt, this time from a presentation given by Bernd Venohr for SAP:

Does IT also perform other fundamental roles for small and midsize companies?

Yes of course. IT plays a vital role in sales and service too, enabling even the smallest of companies to market their products worldwide via the internet. Take Hamburg-based Windpilot, for example, which sells exclusively online and has a website in seven languages. It is the global market leader in the micro market for windvane steering systems for sailing boats with a 60 percent share. And its entire operation is run by just two people.

Surging waters cause yacht and crew to sink in Brisbane

When the Orion broke free of its mooring and ran into floating debris, the damaged vessel began to take on water. Skipper Russell Bentley swam out and climbed on board to assess the damage. A friend sailed out to assist and both men were caught in the sinking boat.

As the yacht rolled over and sank, Bentley hit his head and was taken deep underwater. A nearby police boat later rescued both men.

SV Maus, Manfred Marktel ITA on her way from Salvador de Bahia to Cape Town

SV Lollo, Irmi + Torsten Sude GER

Ein junges Paar, ein altes Schiff – eine HR Monsun 31 – 18 Monate Zeit – und der Wille eine schöne Zeit auf See zu verbringen. Hier kann man lesen, was man alles daraus machen kann! Zum Beispiel eine schöne Atlantik Runde! Hier geht´s zum blog

Ein junges Paar, ein altes Schiff – eine HR Monsun 31 – 18 Monate Zeit – und der Wille eine schöne Zeit auf See zu verbringen. Hier kann man lesen, was man alles daraus machen kann! Zum Beispiel eine schöne Atlantik Runde! Hier geht´s zum blog

What ever happened to boat building? Part #1

Few topics are as controversial among sailors as the quality of the boats we invest in to help realise our dreams of a life afloat. Obviously, choosing a boat ranks as one of the key decisions for any sailor: a choice that proves to have been a poor one can have serious and far-reaching consequences – and is by no means straightforward (or inexpensive) to rectify. Take on too much of a financial burden, leave yourself too much to learn or trust too much to your own handiwork and you could end up in trouble, especially if the press-ganged family, left at the mercy of your orders from the bridge, also has to live with your misjudgements as immortalised in composite, aluminium or steel. A wise choice right at the beginning can make all the difference in the world to the fun to be had under sail, so it seems astonishing that so many of the issues involved are so seldom properly discussed.

Polarised debates of the traditional = better/modern = worse type might be very effective at filling pages on internet forums (in the process bringing out the intransigence, entrenched positions, rapid loss of perspective and ruthless jump to character assassination that seem to have become the staple fare of this platform), but they fall well short of the level of insight required. The issues involved are more complex: expect rough seas ahead!

Polarised debates of the traditional = better/modern = worse type might be very effective at filling pages on internet forums (in the process bringing out the intransigence, entrenched positions, rapid loss of perspective and ruthless jump to character assassination that seem to have become the staple fare of this platform), but they fall well short of the level of insight required. The issues involved are more complex: expect rough seas ahead!

It is quite extraordinary that these matters receive so little consideration in the sailing press, although the fact that our press has become, willingly or unwillingly, so dependent on its advertisers might perhaps have something to do with it. Our would-be critics have simply washed their hands of the whole notion of quality, with any criticism limited to fairly trivial points such as headroom, berth length and interior furnishing. The fundamental properties of a product as a seagoing vessel are seldom even considered, let alone subjected to a rigorous comparative investigation.

It is quite extraordinary that these matters receive so little consideration in the sailing press, although the fact that our press has become, willingly or unwillingly, so dependent on its advertisers might perhaps have something to do with it. Our would-be critics have simply washed their hands of the whole notion of quality, with any criticism limited to fairly trivial points such as headroom, berth length and interior furnishing. The fundamental properties of a product as a seagoing vessel are seldom even considered, let alone subjected to a rigorous comparative investigation.

The transformation of boat building from a craft into an industrial process and, in particular, the implications of this change in terms of the quality and price of the product seem to me to be fundamental issues for our sport and yet they are hardly eating up the column inches. Nothing sets the opinions flying like an open debate on then versus now, but there are a number of distinct aspects to consider if we are to do the subject justice:

The transformation of boat building from a craft into an industrial process and, in particular, the implications of this change in terms of the quality and price of the product seem to me to be fundamental issues for our sport and yet they are hardly eating up the column inches. Nothing sets the opinions flying like an open debate on then versus now, but there are a number of distinct aspects to consider if we are to do the subject justice:

– How boat building has changed from a craft into an industrial process

– Materials and their use

– Speed and seakeeping ability

– Intended and actual purpose

– Lifetime and maintenance requirements

– Marketing and its costs

– Value and resale

Clearly sailing could never have become widely accessible as a sport without the introduction of mass production in GRP. The smaller the boat, the bigger the potential market open to it and hence the more units to be sold. Optimists and Lasers have been churned out in their millions, or least hundreds of thousands, and while yachts have never shifted in these numbers, their extra features – everything from heads to an engine – make them much more interesting in terms of the value to be extracted per unit.

When yacht production first began to move onto something approaching an industrial scale, the small number of manufacturers offering boats at shows in Europe could have sold dozens of each model every time they exhibited. The Seventies and Eighties were gold rush time as sailors beat a path to the boatyard gates and demand soared. Brian Meerlow and his team in England built thousands of their Leisure yachts, for example, back when nobody worried about breathing in styrene vapour and extractors were unheard of.

Coincidentally it was to Brian that the founder of my company, John Adam, turned in 1968 in his search for something small and seaworthy to win him some respite from excessive strife on the domestic front. Armed with a Leisure 17, he headed West and eventually found himself on the beach in Cuba having fallen asleep and run aground. It was while cooling his heels in one of Castro’s prisons that he made the decision to set up Windpilot: the first vane gear had after all passed its test with flying colours (keeping watch – then as now – not being a part of its remit).

Coincidentally it was to Brian that the founder of my company, John Adam, turned in 1968 in his search for something small and seaworthy to win him some respite from excessive strife on the domestic front. Armed with a Leisure 17, he headed West and eventually found himself on the beach in Cuba having fallen asleep and run aground. It was while cooling his heels in one of Castro’s prisons that he made the decision to set up Windpilot: the first vane gear had after all passed its test with flying colours (keeping watch – then as now – not being a part of its remit).

John’s story created a sensation at the time in Germany so that all the marketing professionals in the world could not have coordinated a better market launch for Leisure yachts. The brand retains a special aura to this day, with over 4000 Leisures sold and almost all of them still in existence. But I digress…

The number of people eager to get afloat was simply too high for traditional production methods and craftsmanship to cope. Consumers were no more patient then than they are now: once they felt the itch, they wanted deck beneath their feet and pronto. When it comes to impatience, children on Christmas Eve have nothing on grown men and women waiting for a new boat to arrive. The transformation in the nature of boat building precipitated by these pressures was dramatic. The process was – almost literally – turned upside down (or inside out, depending on your point of view) and ever since, boats have been built the wrong way around: today everything starts with the skin and not the bones.

Henry Ford started exploring the possibilities of assembly line production a century ago, but it would be another 60 years before boat builders first sat up and took notice.

Originally the hull of a boat was a very complex assembly: to keel and keelson, stem, sternpost, stringers, deck beams and ribs were added planks as thick as a seaman’s thumb and the whole thing was bolted, nailed and glued together, sealed, sealed and sealed again and then finally treated to several coats of paint to create a thoroughly robust and watertight structure. All of which took some time…

Originally the hull of a boat was a very complex assembly: to keel and keelson, stem, sternpost, stringers, deck beams and ribs were added planks as thick as a seaman’s thumb and the whole thing was bolted, nailed and glued together, sealed, sealed and sealed again and then finally treated to several coats of paint to create a thoroughly robust and watertight structure. All of which took some time…

A finished hull of this nature came ready to sail; there was no need for extra interior structures or fittings to help spread and absorb the working loads. To keep the weight down, racing yachts often started life with nothing below but pipe berths and were only fully furnished at a later date if and when racing gave way to luxury cruising. Whether to hit the race course with a crack crew or embark family and friends and concentrate on seeing and being seen was a matter for the owner: the yachts were tough enough for both lives – in fact they still are. In those days the cost of the hull made up an eye-watering proportion of the overall price of the boat. Boat builders were craftsmen, not magicians, and bending wood takes time (although of course man hours were not at all expensive in that era).

A finished hull of this nature came ready to sail; there was no need for extra interior structures or fittings to help spread and absorb the working loads. To keep the weight down, racing yachts often started life with nothing below but pipe berths and were only fully furnished at a later date if and when racing gave way to luxury cruising. Whether to hit the race course with a crack crew or embark family and friends and concentrate on seeing and being seen was a matter for the owner: the yachts were tough enough for both lives – in fact they still are. In those days the cost of the hull made up an eye-watering proportion of the overall price of the boat. Boat builders were craftsmen, not magicians, and bending wood takes time (although of course man hours were not at all expensive in that era).

Rationalizing hull construction was the logical way to go – and it is here that the rot set in! Once a female mould had been engineered, ready-made boat shells could be turned out one after the other like so many bread rolls in a process that suddenly no longer needed the expertise of skilled boat builders.

It is characteristic of the modern classics that although they have a GRP hull, they were still fitted out by craftspeople, that is to say skilled boat builders still had a hand – and earned a crust – in their production. Also no secret is the fact that older GRP boats tend to be considerably more solid, because stringers, bearers and wooden interior components are all laminated into the hull. The resulting structure is very stable, especially since the stringers and bearers are bonded face-on and the interior components edge-on.

Take my Hanseat boats, of which I have had three, for example. They were always perfectly quiet to sail even in a good breeze and the deck never creaked even when the summer hoards stampeded across on their way from the far end of the raft to the bar. In those days sailing boats were still seen and not heard.

Take my Hanseat boats, of which I have had three, for example. They were always perfectly quiet to sail even in a good breeze and the deck never creaked even when the summer hoards stampeded across on their way from the far end of the raft to the bar. In those days sailing boats were still seen and not heard.

Modern classics enjoy great popularity today because of the way they combine the beautiful lines and traditional craftsmanship of old with modern materials. And, at a more basic level, because of the way they allow families – even those members with a more sensitive nose – to take to the sea without the damp reek of stale air and musty socks that tends to pervade the more traditional of traditional craft.

There is more to boat building than right angles; indeed their very curvaceousness accounts for a big part of the appeal of those striking little ships whose lines alone set hearts pounding and bank accounts quaking. On a more practical level, it also makes sure that no matter how soundly you slept, you quickly remember that you are on the boat and not in the house. Rights angles really were an unusual sight in this era, which for me explains much of its charm and elegance.

There is more to boat building than right angles; indeed their very curvaceousness accounts for a big part of the appeal of those striking little ships whose lines alone set hearts pounding and bank accounts quaking. On a more practical level, it also makes sure that no matter how soundly you slept, you quickly remember that you are on the boat and not in the house. Rights angles really were an unusual sight in this era, which for me explains much of its charm and elegance.

The visual language of traditional design was emotional: function followed form and not vice versa. Today the mainstream marches to the beat of a different drummer, with aesthetic concept and product shaped by marketing diktats and design vocabulary serving only to ensure brand recognition and distinctiveness.

The visual language of traditional design was emotional: function followed form and not vice versa. Today the mainstream marches to the beat of a different drummer, with aesthetic concept and product shaped by marketing diktats and design vocabulary serving only to ensure brand recognition and distinctiveness.

The boats of the past were undoubtedly more robust. They had a backbone and ribs, meaning they were better armed against ramming, stranding, grounding and other extreme encounters, and carried their rudder firmly mounted and safely tucked away in the sweet spot at the trailing edge of the keel. Modern yacht design specifies no such backbone. It has been spirited away to be replaced, here and there, with other structural members in much the same way that many car manufacturers have done away with any distinct chassis to leave each individual component apparently supported only by the parts around it.

The boats of the past were undoubtedly more robust. They had a backbone and ribs, meaning they were better armed against ramming, stranding, grounding and other extreme encounters, and carried their rudder firmly mounted and safely tucked away in the sweet spot at the trailing edge of the keel. Modern yacht design specifies no such backbone. It has been spirited away to be replaced, here and there, with other structural members in much the same way that many car manufacturers have done away with any distinct chassis to leave each individual component apparently supported only by the parts around it.

Interior shells and moulded parts have increasingly driven traditional boat building out of interior construction too on the basis that separate units and components can be mass-produced rapidly and installed inside a bare hull equally quickly. Boats today are built in a modular fashion, which simplifies customizing and cuts costs. Moulded components can also incorporate rounded edges and corners at no extra cost to suggest at least a token element of design flair.

This video clip of a guided tour of a well-known yard illustrates the modern process. The commentary is in German, but the images really speak for themselves.

Today hulls are reinforced in critical areas with bulkheads, interior shells, longitudinal stringers and space frames to make sure that when the boat is lifted out, the keel comes too, that the engine doesn’t slowly make its way up the boat while motoring and that the pressure transmitted from the mast above when sailing close-hauled does not leave hapless crewmembers marooned in the heads. The most extreme designs include additional metal structures to distribute the loads.

Some would have us believe that modern boats are more solid than ever, but can we really believe that? Space has become a more compelling argument and the obvious response has been to do away with the traditional foundation of a strong hull – its frame and ribs – without putting anything obvious in its place. Sailors flock to the resulting space(ous) ships like moths to a candle, for it seems the number of berths has become the measure of all things (and has a not insignificant effect on the price). And who ever stops to consider how this wonder came to pass? Who seriously spends any time thinking about how much – if any – effective load-bearing structure there is behind that smart interior shell?

Perhaps it’s all a matter of perspective. After all, what we don’t know might not hurt us. Although … once I saw a sailing boat at one of the big boat shows that had been sliced in half longitudinally and I couldn’t help noticing just how little substance there would be between the sailor asleep in a bunk of a heeling yacht and the fish swimming past outside. Did that strike a chord with anyone else?

It is no secret that mast, rigging, sails, engine, keel and rudder pull and push the boat in different directions and that hydraulic systems can put a bend in the hull as well as the mast. Only a stiff hull can endure such loads in the long term; once flexing sets in, serious problems are sure to follow. Signs of fatigue on the hull, keel and rudder, soon our constant companions, auger well for the repair and restoration business.

Everyone understands that the half-life of a new stripped-out racing machine is short, that at some none-too-distant point in the future that once proud and resolute bow will begin to acquiesce a little as the sea builds. Life is a compromise – and when it comes to rig tension, it can be a fine line between just right and ever so slightly too much.

We should also note that thanks to cheap materials and labour – and the fact that in those days nobody realised just how thin they could go – laminated hulls on older boats and those built in the Far East are often extremely thick.

We should also note that thanks to cheap materials and labour – and the fact that in those days nobody realised just how thin they could go – laminated hulls on older boats and those built in the Far East are often extremely thick.

Today it’s a different story altogether!

The greatest secret in the increasing industrialization of modern boat building is probably the sharp reduction in production times and concomitant increase in value added. Or, to put it another way, why do international investors and the pin-striped locusts suddenly have yacht manufacturers in their sights?

I know of one sailor who, out of love for his wife and in preparation for the big retirement cruise, decided to swap his dark cavern of a steel yacht for a new – and much brighter – alternative. Keen to be, as it were, in the delivery room to witness the arrival of his new home from home, he cheerfully turned up one Monday morning at the yard appointed to realise his dreams expecting to witness the final stages of fitting out. What he saw instead was a bare hull that, like him, had only just come into the building. He was astonished – and never more so than when the finished boat was handed over right on time just a few days later.

I have seen similar myself in Les Sables d’Olonnes: the project concerned, an imposing new catamaran, was just a week away from delivery and yet there it stood in the middle of the hall, deckless, looking more like a building site than a boat.

I have seen similar myself in Les Sables d’Olonnes: the project concerned, an imposing new catamaran, was just a week away from delivery and yet there it stood in the middle of the hall, deckless, looking more like a building site than a boat.

Neither I, nor the owner and his wife sitting at home in Bavaria with their sea bags packed and poised, could believe everything would be ready on schedule. But it was – no sweat!

Neither I, nor the owner and his wife sitting at home in Bavaria with their sea bags packed and poised, could believe everything would be ready on schedule. But it was – no sweat!

I always seem to end up comparing money invested in yachts with money spent on property (albeit houses too have their weaknesses with the wind on the nose). In Germany, a new family house in a pleasant setting costs in the region of €200,000 and represents thousands of man hours at a moderate level of value added for all of the companies involved. A production GRP yacht costing a similar amount takes a fraction of the time to create – and is then very often compared in price terms to boats whose construction involves a much larger element of craftsmanship.

It is hardly surprising then that terms like “quality yacht” always seem to be applied to more expensive vessels. Obviously, one-offs assembled by craftspeople are going to consume more money in the shed.

It is hardly surprising then that terms like “quality yacht” always seem to be applied to more expensive vessels. Obviously, one-offs assembled by craftspeople are going to consume more money in the shed.

It may be interesting – perhaps shocking – to reflect a little on the hours of work that go into producing a finished yacht. The conclusions in terms of the inherent value of any given boat soon become perfectly clear: you do indeed get what you pay for (in more ways than one). It can also be interesting to look at the second-hand market and see how perceptions of quality and value change once long-term use has had a chance to expose weaknesses not apparent on the boat show floor. True quality reveals itself only in long-term use and it is no surprise the sailor’s brain spends a long time quietly accumulating information before eventually coming to a judgment for or against a particular brand.

We are honoured almost every week with the launch of some or other new boat, just about all of them production GRP designs. This speaks of serious rationalization on a scale unknown – perhaps even inconceivable – to ordinary sailors. In fact producers have found ways to rationalize their business in all kinds of areas:

– in design, which is entrusted to powerful computers running sophisticated software,

– in mould making, in which robotic systems capable of five-axis CNC machining do all the work without human involvement (with no lunch break and no desire to go home at night),

– in the construction of the bare hull, which is produced using prepreg materials and vacuum bagging,

– with interior shells, which make it possible to reinforce and partition the hull simultaneously,

– with interior fixtures, which are produced as modules on a separate line and can then be installed into boats as required,

– in the production of the deck, which has the fittings installed prior to being dropped onto the fitted-out hull to seal the finished yacht like the lid on a jar.

That such rapid changes of model are even possible is, without exception, down to the enormous rationalization and acceleration of all processes. Even small production runs can be profitable now. Nevertheless even the biggest yards with global marketing and a lively charter supply business still achieve only modest output when compared with the producers of other high-priced goods, which probably explains the breathless pace of competition: production yachts have to be introduced, promoted and phased out again faster than cars just to keep up the pressure on the other big players in the market. A design lasts just a few hundred units before the focus moves on and the next contender sets sail. In a saturated market, however, there is only limited scope to keep sales volumes rising. We do not (yet) have a scrappage programme for old yachts!

Building a metal yacht remains a time-consuming business and the preserve mainly of one-offs. A high-quality 45-foot custom boat in aluminium might take around 5000 hours to build; a GRP equivalent of the same size would almost certainly be ready to hit the water in a fraction of this time. The GRP version would surely be significantly cheaper too, so it wins hands down – unless, perhaps, other factors like seaworthiness, safety, reliability, suitability for bluewater sailing, performance in use, value-holding ability and ease of resale also come into the equation. But that is a discussion for another time.

Building a metal yacht remains a time-consuming business and the preserve mainly of one-offs. A high-quality 45-foot custom boat in aluminium might take around 5000 hours to build; a GRP equivalent of the same size would almost certainly be ready to hit the water in a fraction of this time. The GRP version would surely be significantly cheaper too, so it wins hands down – unless, perhaps, other factors like seaworthiness, safety, reliability, suitability for bluewater sailing, performance in use, value-holding ability and ease of resale also come into the equation. But that is a discussion for another time.

Peter Förthmann

SV Helena Zwo, Helen+Bruno Stalder CH

Steel built Reinke 12m left her homeport sometime in 1998 travelling the world the slow motion way, currently living in Langkawi after spending quite a time Malaysia and Indochina.

Steel built Reinke 12m left her homeport sometime in 1998 travelling the world the slow motion way, currently living in Langkawi after spending quite a time Malaysia and Indochina.

Here is the link to their adventures

SV Wadda, Margaret + Moe from North Dakota US

Current Location: Las Brisas, Panama City

Current Location: Las Brisas, Panama City

Greetings to all our readers and visitors.

We travelled to Gamboa then boarded a canopied panga (long thin dinghy with large outboard), were soon under the old Gamboa bridge and out in the Panama Canal. We briefly stopped to meet some of the local inhabitants and watched some of the canal traffic. After a trip through a very narrow overgrown side channel we stopped for lunch on a houseboat in a protected side lagoon. We met some more residents of the Canal and rainforest ecosystem.

Some folk went kayaking, some snoozed in hammocks, some went fishing. I was very thrifty with my bait fish and at the end of an hour still had the same fish on the end of my hook. We zoomed back across the Canal to Gamboa and had just enough time for a trip to one of the artisan bazaars for some Panamanian handcrafts. Yet another Grand Day Out.

Please have a look to the spectacular pictures of Panama and the surrounding djungle and follow the adventures of this US couple

Sponsoring – competing priorities

The pearl of marketing re-examined in the context of windvane steering systems.

The pearl of marketing re-examined in the context of windvane steering systems.

I made my confession on 28 December 2008 on the German YachtForum board: Laura Dekker was not a familiar name at the time, just a girl who came to see me in Hamburg looking to buy a windvane steering system – and ended up being given one instead.

We all know the score: when it comes to raising children, internet forum regulars have all the answers. That they all have different answers seems not to matter – all at once everyone simply knows they are the perfect parent! Anyway, just like that I found I had mutated – in the eyes of one outraged forumite at least – into a “calculating sponsor” with eyes only for the fortune I stood to make. I was puzzled: did people really think I should have insisted on being paid? What a contorted idea! But then again the whole notion of sponsorship in our sport is rather shaky…

First a few home truths about advertising and sponsorship. Opinions may vary, of course, but I think it is worth highlighting these issues just to illustrate the extent of the wealth to be accumulated through sponsorship in a niche sport like sailing. Sponsors are as much a fact of modern life as the sun, the moon and the stars. Living as we do in a world suffused with elegant marketing ruses, we have it in our head that what sponsors pay, we don’t have to and we find the whole notion thoroughly reassuring. We understand by and large that companies do not engage in sponsorship out of sheer benevolence, still their backing for initiatives and events undoubtedly creates a positive vibe.

The subtler and more delicate a sponsor’s approach, the less likely it is to awaken public suspicion. The neater the fit between sponsor, beneficiary and/or event, the more golden the glow generated – and the smaller the probability that anyone at the bottom end of the food chain will start to wonder who actually picks up the bill.

The subtler and more delicate a sponsor’s approach, the less likely it is to awaken public suspicion. The neater the fit between sponsor, beneficiary and/or event, the more golden the glow generated – and the smaller the probability that anyone at the bottom end of the food chain will start to wonder who actually picks up the bill.

When a well-known carmaker lays on a shuttle service to ferry hotshot sailors from boat to party and back again smoothly during their annual visit to Kiel, for example, the costs for coach and coachman are ‘socialised’: everyone who purchases one of well-known carmaker’s vehicles pays a share of the cost – without ever suspecting a thing! Along the way the brand gains plenty of positive exposure among public and media alike and stealthily merges its identity with that of sailing. And the association of automobiles and yachting, as everyone knows, unleashes waterfalls of testosterone that leave us powerless to resist. At least I believe that’s how it’s supposed to work. Advertising execs are smart folk – many of them sail too…

Cutting a little closer to the bone, consider the example of the bank specialising in shipping finance (apparently banks have no sense of irony) that, having already lost face and parted taxpayers from a handsome sum, decides in the name of those selfsame taxpayers (albeit we, unlike our elected representatives, have no influence whatsoever in its decisions) to sponsor the same nautical event. An institution propped up by our taxes uses money contributed by us to try and set that testosterone flowing in the hope we’ll then dip into our pocket for a third time and help lift it a little further out of the mire into which it has sunk. It couldn’t work without the sheen of respectability afforded by sponsorship.

Cutting a little closer to the bone, consider the example of the bank specialising in shipping finance (apparently banks have no sense of irony) that, having already lost face and parted taxpayers from a handsome sum, decides in the name of those selfsame taxpayers (albeit we, unlike our elected representatives, have no influence whatsoever in its decisions) to sponsor the same nautical event. An institution propped up by our taxes uses money contributed by us to try and set that testosterone flowing in the hope we’ll then dip into our pocket for a third time and help lift it a little further out of the mire into which it has sunk. It couldn’t work without the sheen of respectability afforded by sponsorship.

Ultimately there is no escaping the fact that any form of plugging is paid for by the customer. Assuming the process is handled with discretion, of course, the customer hardly notices, but marketing and advertising write their own rules and it seems a pretty safe bet that, whatever the product, the price you pay includes the costs of its promotion. Manufacturers’ efforts first to catch our eye and then convert our interest into money on the counter add between €640 and €4,000 on average to the price of every new car from one of the familiar German marques – and we are talking here about mass-produced items.

The costs for advertising, boat shows, marketing and so on incorporated into the prices we pay to turn our sailing dreams into reality must be astronomic by comparison on a per-boat basis. Can I even say that here or is it just too painful to mention?

Sponsorship as a magic formula was conceived by strategists to kill a whole flock of important birds with a single stone, to defray the costs of the “show” in small amounts across innumerable consumers of the sponsor’s products in pursuit of the relevant commercial Greater Good. The smart weapon of marketing professionals, it really is advertising in disguise: we barely notice the cleverly positioned brand logo, but it nestles itself into a cosy corner somewhere up inside our brain and suddenly we can’t even begin to think about some of the prestigious offshore races without instantly being reminded of a certain rather expensive Swiss watch. And with the right media exposure – the media plays a critical role in conveying the message effectively to its target audience – that single well placed logo can reach untold numbers of people, improving the marketing economics with every new pair of eyes it passes.

Sponsorship as a magic formula was conceived by strategists to kill a whole flock of important birds with a single stone, to defray the costs of the “show” in small amounts across innumerable consumers of the sponsor’s products in pursuit of the relevant commercial Greater Good. The smart weapon of marketing professionals, it really is advertising in disguise: we barely notice the cleverly positioned brand logo, but it nestles itself into a cosy corner somewhere up inside our brain and suddenly we can’t even begin to think about some of the prestigious offshore races without instantly being reminded of a certain rather expensive Swiss watch. And with the right media exposure – the media plays a critical role in conveying the message effectively to its target audience – that single well placed logo can reach untold numbers of people, improving the marketing economics with every new pair of eyes it passes.

Sponsorship largely remains the preserve of big companies keen to exploit its direct emotional appeal in their constant search for a stronger and more distinctive profile, but humanitarian objectives, environmental protection, big boys’ toys, a round-the-world race and even perfectly ordinary sporting events can be packaged up in a form that creates financial value enough for all. Sponsoring can be quite a gamble too. Large sums of money are put on the line with no way of predicting the return in advance: the mechanism only works if the masses hand over their heard-earned for the right cause, the right beer and the right phone, if they embrace the opportunity to release their inner dynamic athlete and order that Global Race Special Edition car (to spend sweaty hours in stationary traffic dreaming of the ocean), if they drink the right energy drink and feel the hand of Schumacher in their driving (he’s the one with the red hat and the airline, right – or am I thinking of someone else?).

Sponsorship relies on an alliance between the sponsor, the beneficiary, the media that bring the event to the public’s attention and the customers who willingly – or at least unwittingly – stump up the funds. So when a well-known energy drink brand decides to sponsor Driver X, he reaps millions, the proprietor gets a new aeroplane, ordinary drivers park themselves in front of the TV and the ‘right’ kind of blue can carries a rather hefty price tag (but there is after all a world champion in every one).

It’s a sterling deal, but the figures only add up in the context of cars, football, fashion, the world of the wealthy, the beautiful and the nipped and tucked – in short, wherever ordinary people stand in line for a chance to bask in the reflected glory of the celebrities of the day (albeit the reflection comes from the TV and most of the basking is done from the comfort of the couch). The world of sailing appears unpromising by comparison: with no ball to kick, no stadium to sit in and no prospect of really becoming a sport of the people, our sport does not lend itself to mobilizing the masses.

It’s a sterling deal, but the figures only add up in the context of cars, football, fashion, the world of the wealthy, the beautiful and the nipped and tucked – in short, wherever ordinary people stand in line for a chance to bask in the reflected glory of the celebrities of the day (albeit the reflection comes from the TV and most of the basking is done from the comfort of the couch). The world of sailing appears unpromising by comparison: with no ball to kick, no stadium to sit in and no prospect of really becoming a sport of the people, our sport does not lend itself to mobilizing the masses.

The exception is France, where heroes returning from the Vendée Globe can look forward to a parade along the Champs-Élysées. Even foreign competitors command public attention and respect in France, an almost inconceivable scenario elsewhere. The broad-based popularity of sailing in France provides sufficient oil to keep the wheels of serious sponsorship turning. Prominent backers include regional banks, food producers, newspapers, insurers, breweries – all the types of company that can build a sponsorship budget out of minor contributions from millions of customers happy to see ‘their’ brand in pole position on screen, billboards and the printed page. We should be so lucky!

The French way gives ace sailors the perfect opportunity to enjoy the best in equipment and resources while also helping their own star shine a little brighter. However sponsorship inevitably also adds to the pressure on the heroes of the great races: sponsors are a whip that drives boats and crews to their limits and at times perhaps beyond. Sponsorship on this scale is most definitely business first: agents, lawyers and the like gather to define rights and obligations in painstaking detail to minimise collateral damage on all sides in the event of failure and ensure there are no long faces at the end. The sums involved are significant – too significant for anything but the most formal legal arrangements. Apparently it is not unheard of for ownership of a boat to be transferred to its skipper bit by bit as each stage of the race is successfully completed (assuming, of course, that neither runs out of strength, nerve or luck along the way).

The French way gives ace sailors the perfect opportunity to enjoy the best in equipment and resources while also helping their own star shine a little brighter. However sponsorship inevitably also adds to the pressure on the heroes of the great races: sponsors are a whip that drives boats and crews to their limits and at times perhaps beyond. Sponsorship on this scale is most definitely business first: agents, lawyers and the like gather to define rights and obligations in painstaking detail to minimise collateral damage on all sides in the event of failure and ensure there are no long faces at the end. The sums involved are significant – too significant for anything but the most formal legal arrangements. Apparently it is not unheard of for ownership of a boat to be transferred to its skipper bit by bit as each stage of the race is successfully completed (assuming, of course, that neither runs out of strength, nerve or luck along the way).

The infinitely more modest proposals of typical amateur sailors seeking sponsorship simply to make their own life afloat a little easier seem almost touching by comparison. The prospects of reaching an audience of any real size in print and on TV elsewhere in the world are poor – after all sailing is at best the preserve of the inside pages and late broadcast slots – and the proposition for sponsors is correspondingly less attractive. When companies do decide to try their luck with our sport and attempt to generate publicity and excite the masses through sailing, they have to accept that in this arena, success cannot be guaranteed in advance. Perhaps not surprisingly, the sponsorship that does flow into sailing tends to be targeted at higher level racing events where national pride is on the line. There is just no more reliable way to secure the emotional involvement of consumers.

Sponsoring in the context of long-distance cruising, in contrast, usually amounts to nothing more glamorous than a simple exchange, a touchingly naïve arrangement ordinarily framed in the simplest of terms: you give me a blanket or a windvane steering system and I’ll tell everyone that I sleep well when George is driving. Not infrequently, however, competing priorities take over and fairness falls by the wayside to be replaced with promises of “media attention”, a scarcely measurable commodity at the best of times and one the party doing the promising may well – aside from a few courteous mentions in the ship’s own blog – have no concrete means to deliver. Not everyone views their word as their bond either and assurances given on shore can quickly fade once the voyage is under way.

Sponsoring in the context of long-distance cruising, in contrast, usually amounts to nothing more glamorous than a simple exchange, a touchingly naïve arrangement ordinarily framed in the simplest of terms: you give me a blanket or a windvane steering system and I’ll tell everyone that I sleep well when George is driving. Not infrequently, however, competing priorities take over and fairness falls by the wayside to be replaced with promises of “media attention”, a scarcely measurable commodity at the best of times and one the party doing the promising may well – aside from a few courteous mentions in the ship’s own blog – have no concrete means to deliver. Not everyone views their word as their bond either and assurances given on shore can quickly fade once the voyage is under way.

When an author approached me 35 years ago to ask if I would like to sponsor his ‘rugged’ self-built yacht by supplying one of my Atlantik auxiliary rudders, my response was no and no: not only was I less than enthusiastic about giving away products for free, but I also felt the boat concerned was too heavy for my system at the time. In the end the author bought my unit anyway (for what his subsequent book described as obvious reasons) and I had the dubious pleasure of reading about how it had been steadily optimised until, by the end of the voyage, it had actually been made to work. Imagine that as the payback on a sponsorship deal!

I had a similar experience with another well-known individual who was dead set on completing the Northwest Passage (he did it too, only on foot, as his boat became stuck in the ice). Here too I declined to sponsor and instead sold the skipper one of my systems, which was promptly installed wrongly and then operated equally badly. It never stood a chance – and the photo that proved it appeared on the front of German sailing magazine YACHT. The slick aluminium yacht concerned subsequently had a stainless steel windvane system fitted in California. As a sponsorship move this was undoubtedly a red-letter day for my fellow windvane purveyor in the US, but months later YACHT magazine published a report in which the individual concerned outlined the various improvements he had had to make to get the (by no means unproven) new system working properly. The boat itself is still sailing, although it passed many years ago to a new owner who reports on his comparison of autopilot and windvane systems in the current edition of YACHT.

I had a similar experience with another well-known individual who was dead set on completing the Northwest Passage (he did it too, only on foot, as his boat became stuck in the ice). Here too I declined to sponsor and instead sold the skipper one of my systems, which was promptly installed wrongly and then operated equally badly. It never stood a chance – and the photo that proved it appeared on the front of German sailing magazine YACHT. The slick aluminium yacht concerned subsequently had a stainless steel windvane system fitted in California. As a sponsorship move this was undoubtedly a red-letter day for my fellow windvane purveyor in the US, but months later YACHT magazine published a report in which the individual concerned outlined the various improvements he had had to make to get the (by no means unproven) new system working properly. The boat itself is still sailing, although it passed many years ago to a new owner who reports on his comparison of autopilot and windvane systems in the current edition of YACHT.

Approached in early 2009 about the possibility of sponsorship for a double circumnavigation project, I went to see the man involved, viewed the boat, whose previous owner I knew, explained my concerns to the new owner, whom I also knew, and offered to sell him one of my systems instead. The outcome this time is a matter of record too: the owner passed up my offer, but I can’t say I was disappointed, as the system he fitted instead ended up being implicated twice over in the failure of his record attempt. Not exactly music to the ears of a sponsor, especially since the facts of the matter tell a rather different story.

Last week it was the turn of a young and attractive Finnish lady, the author of a lively blog adorned with copious bikini shots, who had fallen for a Spanish single-handed yachtsman at a party in Barcelona, moved into his bunk, suddenly considered herself a yachtswomen and – even more suddenly – decided it was time to sail around the world. The open and direct circular she sent out to all vanegear manufacturers proffering media attention and exciting blogs (and not forgetting to mention those photos) makes no secret of her criteria: “We have decided that saving money is important for us (especially now so close to departure!) and we will have to go for a brand that could offer us a greater discount.” I find her willingness to cut straight to the chase disarming: it’s all about the money. Honest, credible … but somewhat wide of the mark as a sponsorship proposal.

A pragmatist living in a small world, I still consider word-of-mouth to be a reliable marketing strategy. It might take a bit longer (almost a lifetime as it sometimes seems), but is dependable and – if you are prepared to leave time, effort and dedication out of the equation – favourably priced. Hence my regular response to solicitations of sponsorship, which are as much a part of my life as the ebb and the flood, remains that the best endorsement a product can have is that people are willing to pay for it: if “good no cheap, cheap no good”, then what of free? I have strayed from this path now and again though and have collected some amusing human interest stories for my trouble.

A pragmatist living in a small world, I still consider word-of-mouth to be a reliable marketing strategy. It might take a bit longer (almost a lifetime as it sometimes seems), but is dependable and – if you are prepared to leave time, effort and dedication out of the equation – favourably priced. Hence my regular response to solicitations of sponsorship, which are as much a part of my life as the ebb and the flood, remains that the best endorsement a product can have is that people are willing to pay for it: if “good no cheap, cheap no good”, then what of free? I have strayed from this path now and again though and have collected some amusing human interest stories for my trouble.

Once upon a time there was a melancholy singlehander who intended to set sail for New Zealand from the Baltic in October in a 7m yacht with no engine. He twice reached the Skaw at the Northern tip of Denmark before eventually thinking better of it, sailing home and selling his boat on eBay in time to fly down under for Christmas. My wife and I had become very fond of this man, a master carpenter, and are reminded of him every time we sit on the two beautiful and unique chairs of his own making that were left orphaned when he sold up and headed South.

Then there is the single man to whom we opened out hearts and gave a few days and nights of therapy who subsequently thought nothing of descending on us again unannounced with his girlfriend in tow. Good manners would suggest asking first, but apparently not to everyone. Had he asked first, we would certainly have declined in the circumstances. As it was, the visit lasted the brief but intense five minutes it took my wife to tell them how things stood and singlehandedly send them on their way. I could never have dealt with the situation so effectively, but fortunately I was out shopping for a bolt at the time and only found out about the whole business later by phone. The plain truth can be brutal, but at least it is the truth.

I am struck by just how few of the really prominent figures in the sailing world attempt to leverage their name for favours – at least in the vital matter of procuring a windvane steering system.

The first German to sail around the world singlehanded (who later also became the first German to complete a solo circumnavigation in both directions) used a vanegear borrowed from a robust Colin Archer design whose owner had found it superfluous after relocating to British Columbia.

The first German to sail around the world singlehanded (who later also became the first German to complete a solo circumnavigation in both directions) used a vanegear borrowed from a robust Colin Archer design whose owner had found it superfluous after relocating to British Columbia.

Another of our best-known sailors here in Germany, a circumnavigator, prolific author and one-time judge, bought a system from me in the usual manner. I installed it for him personally, which isn’t always part of the deal, and he then treated us to a meal of lobster, which is – sadly – very seldom part of any of the deals I do. Lobster is an excruciatingly expensive pleasure in our latitudes and I consequently remember this particular sale very fondly.

Another of our best-known sailors here in Germany, a circumnavigator, prolific author and one-time judge, bought a system from me in the usual manner. I installed it for him personally, which isn’t always part of the deal, and he then treated us to a meal of lobster, which is – sadly – very seldom part of any of the deals I do. Lobster is an excruciatingly expensive pleasure in our latitudes and I consequently remember this particular sale very fondly.

Looking further West, I once travelled to Le Havre to drill my magic four holes in a gleaming new OVNI. The boat and its owner became legends and I gained a friendship that has brought all manner of interesting twists and turns – none of them at all connected with sailing.

Looking further West, I once travelled to Le Havre to drill my magic four holes in a gleaming new OVNI. The boat and its owner became legends and I gained a friendship that has brought all manner of interesting twists and turns – none of them at all connected with sailing.

I am reminded also of a certain tram conductor from Austria. His tiny yacht was plastered with advertising from stem to stern, but he too had no hesitation in paying for his windvane.

I have long since lost count of the requests for sponsorship and promises to light up my brand, but I know that in all but a few exceptional cases in which something special caught my eye, my response has always been the same. Sometimes, I admit, I have fallen foul of the competing priorities and missed a trick by failing – or maybe just being unwilling – properly to weigh up the exchange. But that might be just as well.

Age could be a factor too: what hope for a bright young thing seeking sponsorship in exchange for no more than promises of the moon and the stars when the target of the pitch – 63 years old and motivated by the fun and enjoyment his work brings rather than the potential financial rewards – is already perfectly familiar with the heavenly bodies. It hardly helps, of course, that only one side stands to gain something it really wants from the deal. Something for nothing, that is …

Peter Foerthmann

SV Bika, Nina+Henrik Nor Hansen NOR

Norwegian couple, sailing Bika, a Contessa 26, around the world. We left Norway in 2005, and are currently sailing down the Mexican coast.

Norwegian couple, sailing Bika, a Contessa 26, around the world. We left Norway in 2005, and are currently sailing down the Mexican coast.

Nihilism and Photography. Most places aren’t really that interesting. I’m stating this as a fact: it’s mainstream living and nothing more. But here’s where photography makes a twist: it opens up a place. What used to be boring could suddenly become the only thing worth shooting.

I guess this is the main reason why photography has taken such a hold on me, although I sense something way darker underneath this enthusiasm, a kind of sadness, or nihilism, when an idea empties out and the photographs stops radiating.

Nina and Henrik are professional writers having published many articles about their journey in different magazins. Here is the link to many of their articles.

SV Yovo, Bruno Daguzan FRA

![P1010022 [1600x1200]](https://windpilot.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/P1010022-1600x1200-1024x766.jpg) Jeanneau Sun Legende 41 autour du monde. Started at her homeport in France 2007

Jeanneau Sun Legende 41 autour du monde. Started at her homeport in France 2007 ![05 - Niue - course de radeaux (12) [1600x1200]](https://windpilot.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/05-Niue-course-de-radeaux-12-1600x1200-1024x768.jpg) passed Gibraltar towards the Canaries later the year to go West in the same winter.

passed Gibraltar towards the Canaries later the year to go West in the same winter.

![Poissons Raiatea-Tahaa (1) [800x600]](https://windpilot.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/Poissons-Raiatea-Tahaa-1-800x600.jpg) Visiting the Antilles, Curacao, Trinidad, Venezuele, La Tortuga and Les Roques 2008 to cross Panama Canal in march 2009. Guatemala, Galapagos, Marquesa, French Polynesia, Raiatea and Bora Bora were the following places. To follow their route please read their blog in French language

Visiting the Antilles, Curacao, Trinidad, Venezuele, La Tortuga and Les Roques 2008 to cross Panama Canal in march 2009. Guatemala, Galapagos, Marquesa, French Polynesia, Raiatea and Bora Bora were the following places. To follow their route please read their blog in French language

SV Nada, Stine + Andreas SWE

Laurin 31 ketch rigged built in 1968 needed some careful upgrade and restauration before the start for her Atlantic circle some time in summer 2010.

Laurin 31 ketch rigged built in 1968 needed some careful upgrade and restauration before the start for her Atlantic circle some time in summer 2010.

The boat is being performed by a Windpilot Atlantic auxiliary rudder system of 1973.

The boat is being performed by a Windpilot Atlantic auxiliary rudder system of 1973.

The boat and her owners passed Germany, went through Nederlands waters to go South. They did the traditional way for the Canaries,

The boat and her owners passed Germany, went through Nederlands waters to go South. They did the traditional way for the Canaries,

where they arrived in november2010, visited the Cape Verdies to head West for Grenada where the arivved just some days ago.

where they arrived in november2010, visited the Cape Verdies to head West for Grenada where the arivved just some days ago.

The idea is to do the Atlantic circle and return to their home country in 2011. If Swedish is your language, you may join them here

The idea is to do the Atlantic circle and return to their home country in 2011. If Swedish is your language, you may join them here

SV Felicia, Tomas Larsson SWE

Laurin 32 started from her homeport in Stockholm in summer 2010 and excaped to the South. Passed Guernsey late october to pass the Bay of Biscay late season. Arrived in the Canaries mid of november to head West in december. They arrived safely in Barbados last week to stay for the European winter in warm waters – at least. Here is the way to join them

Laurin 32 started from her homeport in Stockholm in summer 2010 and excaped to the South. Passed Guernsey late october to pass the Bay of Biscay late season. Arrived in the Canaries mid of november to head West in december. They arrived safely in Barbados last week to stay for the European winter in warm waters – at least. Here is the way to join them

SV Ballerina, Gesa+Onno Hurdelbrink GER

Baltic 51 mit Windpilot Pacific, die über die Notpinne steuert.

Baltic 51 mit Windpilot Pacific, die über die Notpinne steuert.

Sehr geehrter Herr Förthmann,

sind gut auf den kapverden angekommen. Nach unserem start sollte nun auch der windpilot zum einsatz kommen. Nach wenigen vergeblichen Versuchen klappte es und wir waren uns einig: GENIAL!!. Es macht riesig Spaß und die Anlage steuerte bei halben bis vor dem wind sauber ohne große ausschläge – wir hatten zu keiner Zeit die Befürchtung einer Patenthalse. An der Feineinstellung beim Kurswechsel müssen wir noch üben aber dies kriegen wir sicherlich hin. Die Pinne machte nur ganz geringe ausschläge, obwohl wir bis ca 25 kn Wind und ca. 4 m achterliche Welle hatten. Unterwegs mußten wir die Knoten der steuerseile an dem Augbolzen erneuern und einmal löste sich der augbolzen selbsttätig von der Anlage – zum Glück klebte die Schraube durch das fett und ging nicht verloren. Kurz vorm Ziel bemerkten wir einen Steuerfehler und stellten fest, daß unsere Niro-Ruderpinne am Ansatzstück- wo das schräg nach oben ging- gebrochen war. Dies war offensichtlich nicht gut gearbeitet und wir lassen es hier reparieren und verstärken. Auch die Pinnenhalterung für die Kette hatte sich losgerappelt – man sollte doch immer mal kontrollieren und nachzuziehen.

Alles in allem – großes Kompliment für Ihre Anlage und wir bedanken uns nochmal für Ihren Besuch bei uns an Bord.

Mit freundlichen Grüßen Gesa und Onno Hurdelbrink SY Ballerina z.zt. Mindelo Kapverden

SV Swan of Tuonela, Judy+Anthony Gifford CAN

Bruce Roberts 45 started from her homeport in Ontario, Canada sometime in 2007, slowly sailed down the Eastcoast of the United States, entering warmer waters quite a time later, went snorkelling in the Bahamas and entered the Carribbean waters afterwards. If you never thought that the silent world below the surface of the oceans might be able to attract you – just follow to admire the attached pictures here – perhaps you will change your mind – visitng Judies blog please follow the road here….

Bruce Roberts 45 started from her homeport in Ontario, Canada sometime in 2007, slowly sailed down the Eastcoast of the United States, entering warmer waters quite a time later, went snorkelling in the Bahamas and entered the Carribbean waters afterwards. If you never thought that the silent world below the surface of the oceans might be able to attract you – just follow to admire the attached pictures here – perhaps you will change your mind – visitng Judies blog please follow the road here….

SV Forty Two, Mercedes+Carsten Borchardt GER

Mercedes and Carsten first met in 2000 at the Baltic Germany during sailing .

Mercedes and Carsten first met in 2000 at the Baltic Germany during sailing .

It just took some months to realize that they were destined to walk together.

It just took some months to realize that they were destined to walk together.

Soon afterwards they decided to have a plan, the idea of a circumnavigation arose,

Soon afterwards they decided to have a plan, the idea of a circumnavigation arose,

a Westerly Fulmar 32 has been purchased in Guernsey Channel Islands,

a Westerly Fulmar 32 has been purchased in Guernsey Channel Islands,

headed for a Round Brittain circle soon afterwards. The years passed by, the boat has

headed for a Round Brittain circle soon afterwards. The years passed by, the boat has

been upgraded with useful equipment, the appartment got emptied, the car was sold and

been upgraded with useful equipment, the appartment got emptied, the car was sold and

the Fairwell Pary in Hamburg City Marina was quickly done: 18.5.2009 this was

the Fairwell Pary in Hamburg City Marina was quickly done: 18.5.2009 this was

the day of departure. Todays we got some pictures of their adventures during some weeks,

the day of departure. Todays we got some pictures of their adventures during some weeks,

just some of the many impressions they have published via their own blog.

just some of the many impressions they have published via their own blog.  They just passed the Panama Canal to head for Galapagos soon – and the open Pacific with direction West. Please follow their trip here – in German language

They just passed the Panama Canal to head for Galapagos soon – and the open Pacific with direction West. Please follow their trip here – in German language