SWISS ARMY KNIFE MADE IN FRANCE

Designed and constructed for long-distance sailing and yet perfect for hopping around shallow bays and inlets: what more could the prospective bluewater adventurer ask for? These unconventional (outside France at any rate) yachts would almost certainly be even more popular were it not for the cost of squeezing so much versatility into one capable package.

Designed and constructed for long-distance sailing and yet perfect for hopping around shallow bays and inlets: what more could the prospective bluewater adventurer ask for? These unconventional (outside France at any rate) yachts would almost certainly be even more popular were it not for the cost of squeezing so much versatility into one capable package.

Although they are manufactured in small production runs, the boats are to all intents and purposes one-offs, which always has an impact on price. They are built in aluminium too, which comes at a cost but also gives them the unique selling point that sets them apart in a market awash with mass-produced GRP craft. GRP hulls may be cheaper up front, but they cannot hold a candle to their aluminium sisters in a whole range of key areas.

Although they are manufactured in small production runs, the boats are to all intents and purposes one-offs, which always has an impact on price. They are built in aluminium too, which comes at a cost but also gives them the unique selling point that sets them apart in a market awash with mass-produced GRP craft. GRP hulls may be cheaper up front, but they cannot hold a candle to their aluminium sisters in a whole range of key areas.

Fashioning a yacht from thousands of individually shaped pieces of aluminium inevitably requires vastly more man hours than moulding and assembling a GRP hull, deck and internals, which not only accounts for a large part of the price difference but also explains why the yards working in aluminium deliver relatively few boats per annum and why their lead times are so long.

Fashioning a yacht from thousands of individually shaped pieces of aluminium inevitably requires vastly more man hours than moulding and assembling a GRP hull, deck and internals, which not only accounts for a large part of the price difference but also explains why the yards working in aluminium deliver relatively few boats per annum and why their lead times are so long.

Garcia yachts enjoy an excellent reputation in the global cruising community on account of their great robustness, with the wonderful semi-custom models of the Passoa range particularly sought-after in the second-hand market.

Garcia yachts enjoy an excellent reputation in the global cruising community on account of their great robustness, with the wonderful semi-custom models of the Passoa range particularly sought-after in the second-hand market.

Allures and Garcia today form part of an extensive range of boats manufactured and marketed worldwide under theGrand Large Yachting name. The hulls are manufactured and welded in batches of three on adjustable assembly “tables” then flipped and moved on to be fitted out in the conventional manner, leaving the “tables” free to be retooled ready for the next project. There are two separate production sites.

Working with aluminium requires a vastly deeper skillset than building the same types of structure in GRP: it takes a considerable amount of training (and a considerable amount of specialist machinery and equipment) to shape and weld aluminium and craftspeople with the necessary expertise are highly valued by the yards that employ them (and also by other yards that sometimes try to tempt them away). What few boat show visitors realise is that each yard keeps a very close eye on the quality of the welds on its competitors’ products – and on the welding methods and generator types used to create them – in the pursuit of an ever more perfect surface finish. Imitation in this business is absolutely the sincerest form of flattery.

Working with aluminium requires a vastly deeper skillset than building the same types of structure in GRP: it takes a considerable amount of training (and a considerable amount of specialist machinery and equipment) to shape and weld aluminium and craftspeople with the necessary expertise are highly valued by the yards that employ them (and also by other yards that sometimes try to tempt them away). What few boat show visitors realise is that each yard keeps a very close eye on the quality of the welds on its competitors’ products – and on the welding methods and generator types used to create them – in the pursuit of an ever more perfect surface finish. Imitation in this business is absolutely the sincerest form of flattery.

I believe almost all the leading yards in Europe (most of them located in France or the Netherlands) use Fronius welding equipment, which makes it possible to achieve flawless welds and rule out deformation almost completely by means of preheating. Sailors with money waiting to be spent will want to compare the quality of surface finish offered, including by yards here in Germany, before making their final decision, particularly as any remedial work (even simple filling and painting) required to bring the finish up to standard will negate one of the most fundamental advantages of 5083 grade aluminium as a material, namely its ease of maintenance in maritime applications (a side-effect of which is that collecting a small scratch here or there while coming alongside, for example, is an utterly trivial matter). Jimmy Cornell once explained the difference between steel and aluminium like this:

I believe almost all the leading yards in Europe (most of them located in France or the Netherlands) use Fronius welding equipment, which makes it possible to achieve flawless welds and rule out deformation almost completely by means of preheating. Sailors with money waiting to be spent will want to compare the quality of surface finish offered, including by yards here in Germany, before making their final decision, particularly as any remedial work (even simple filling and painting) required to bring the finish up to standard will negate one of the most fundamental advantages of 5083 grade aluminium as a material, namely its ease of maintenance in maritime applications (a side-effect of which is that collecting a small scratch here or there while coming alongside, for example, is an utterly trivial matter). Jimmy Cornell once explained the difference between steel and aluminium like this:

On a steel yacht, the paintbrush for touching up bumps and scrapes never has a chance to dry whereas when somebody puts a scratch on your aluminium hull you just wish them good day and forget about it.

An aluminium boat will forgive many a minor transgression. If the same were true of GRP boats, the whole spectacle of watching (from a safe spot on dry land with no boat of one’s own in the firing line) the succession of inexperienced skippers with little grasp of manoeuvring under engine (but an unshakeable conviction that speed is their friend) try to make it back to their slot in the marina unscathed on a busy evening wouldn’t be half so entertaining.

An aluminium boat will forgive many a minor transgression. If the same were true of GRP boats, the whole spectacle of watching (from a safe spot on dry land with no boat of one’s own in the firing line) the succession of inexperienced skippers with little grasp of manoeuvring under engine (but an unshakeable conviction that speed is their friend) try to make it back to their slot in the marina unscathed on a busy evening wouldn’t be half so entertaining.

credits: Joachim Willner

This, I have to say, is a planning oversight with long-term consequences for life at sea, as an increasing number of less experienced owners with big bluewater plans are now starting to realise. Does the matter receive the attention it deserves in seminars, specialist books and our sailing magazines? I am not convinced it does and I suspect there are many sailors who become aware of their error only once they have already cast off and it is too late to do anything about it. Unprotected rudders are a real gamble for serious long-distance sailing: every crew needs to decide for itself how it likes the odds. Perhaps not everyone has been giving the sea the respect it deserves? I hope the rethink the recent incidents have forced us into will trigger lasting changes in the market.

This, I have to say, is a planning oversight with long-term consequences for life at sea, as an increasing number of less experienced owners with big bluewater plans are now starting to realise. Does the matter receive the attention it deserves in seminars, specialist books and our sailing magazines? I am not convinced it does and I suspect there are many sailors who become aware of their error only once they have already cast off and it is too late to do anything about it. Unprotected rudders are a real gamble for serious long-distance sailing: every crew needs to decide for itself how it likes the odds. Perhaps not everyone has been giving the sea the respect it deserves? I hope the rethink the recent incidents have forced us into will trigger lasting changes in the market.

The biggest difference between mass-produced GRP boats and the aluminium boats manufactured by yards like Garcia probably involves how they are used. Mass-produced boats are designed for a broad cross-section of potential purchasers. They need to be inexpensive to manufacture, which means using the same hull concept to realise all manner of different versions for different segments of the market, and they need to combine a convenient draught with decent performance and pointing: nobody likes to see a succession of boats overtaking to leeward every time they venture afloat.

What it ultimately boils down to is whether a boat is intended for round the buoys, round the bay or round the world. Planning errors are soon laid bare once at sea. And it does happen: boats that have run into problems can be found in just about every port and harbour if you listen carefully enough.

AThe French sailing Swiss Army Knives also have other advantages that should be of great interest to cruising sailors the world over.

AThe French sailing Swiss Army Knives also have other advantages that should be of great interest to cruising sailors the world over.

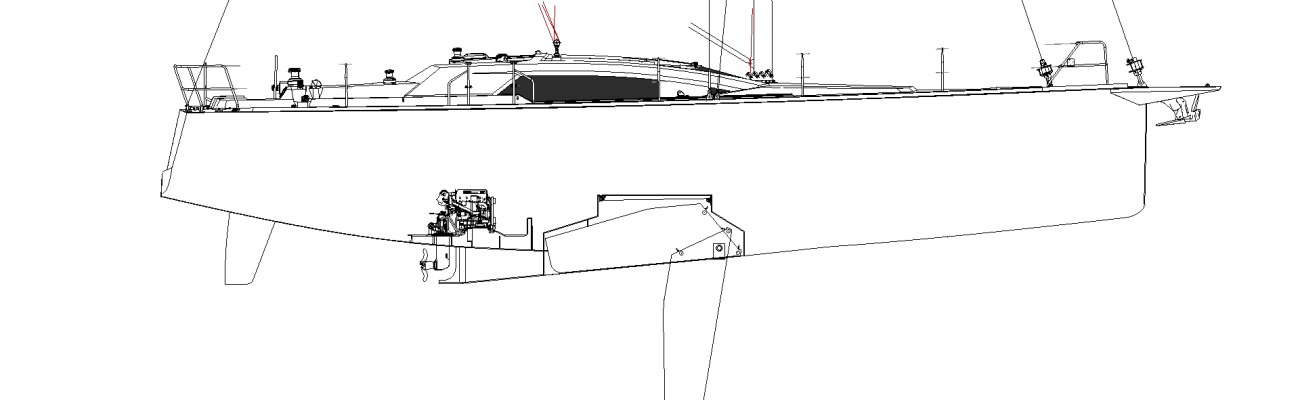

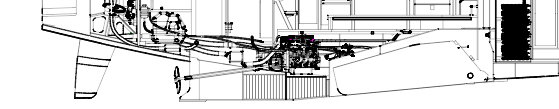

All the French designs with an integral centreboard and internal ballast are able to take the ground and settle in a level position. They are an entirely different beast in this respect to earlier keel centreboard designs on which the centreboard (with or without ballast) retracts into a protruding case that causes the hull to lie at an angle (an unhelpful angle for anyone trying to live on board) as the tide ebbs.

All the French designs with an integral centreboard and internal ballast are able to take the ground and settle in a level position. They are an entirely different beast in this respect to earlier keel centreboard designs on which the centreboard (with or without ballast) retracts into a protruding case that causes the hull to lie at an angle (an unhelpful angle for anyone trying to live on board) as the tide ebbs.  aluminium siblings from Alubat, Boreal and Allures/Garcia all share similar key design features: a very broad beam and internal ballast to improve righting moment plus flattened U-shaped frames in the central area of the hull to enable the boat to settle comfortably and securely level as the tide retreats, removing the need for the “legs” so often seen on boats that dry out in England.

aluminium siblings from Alubat, Boreal and Allures/Garcia all share similar key design features: a very broad beam and internal ballast to improve righting moment plus flattened U-shaped frames in the central area of the hull to enable the boat to settle comfortably and securely level as the tide retreats, removing the need for the “legs” so often seen on boats that dry out in England.

The weather helm problem for which Ovni yachts once had a reputation has long since been resolved; in fact the all-around design of integral centreboard boats has advanced in leaps and bounds in France to the extent that almost all examples are now light on the rudder and only develop significant weather helm once quite well heeled, which is a natural consequence of their beaminess.

The weather helm problem for which Ovni yachts once had a reputation has long since been resolved; in fact the all-around design of integral centreboard boats has advanced in leaps and bounds in France to the extent that almost all examples are now light on the rudder and only develop significant weather helm once quite well heeled, which is a natural consequence of their beaminess.

The concept underlying the design of craft of this type is explained in detail by the GLY yard hier beschrieben.

The ability to sail close to the wind obviously comes fairly far down the list of desirables when designing boats like these that are not at all intended for short-course racing. All that heavy internal ballast does not help with pointing either, but heavy weather sailing would be a much more unpleasant prospect without it. The broad stern and long waterline of course permit long day’s runs on the more comfortable courses favoured by bluewater sailors.

The ability to sail close to the wind obviously comes fairly far down the list of desirables when designing boats like these that are not at all intended for short-course racing. All that heavy internal ballast does not help with pointing either, but heavy weather sailing would be a much more unpleasant prospect without it. The broad stern and long waterline of course permit long day’s runs on the more comfortable courses favoured by bluewater sailors.

Having mentioned that Alubat, Boreal and Allures/Garcia all share important common features, I should probably also point out some key differences, especially as they explain why I am concentrating mainly on Allures/Garcia here. Alubat and Boreal both build to hard chine designs, whereas the Allures and Garcia Exploration yachts have round bilges, which makes them visually very appealing (to my eye at least) but also has significant cost implications.

Having mentioned that Alubat, Boreal and Allures/Garcia all share important common features, I should probably also point out some key differences, especially as they explain why I am concentrating mainly on Allures/Garcia here. Alubat and Boreal both build to hard chine designs, whereas the Allures and Garcia Exploration yachts have round bilges, which makes them visually very appealing (to my eye at least) but also has significant cost implications.

It is no coincidence that the Allures/Garcia yard has two separate production lines. The two brands together cover all relevant applications but each has its own distinct niche:

It is no coincidence that the Allures/Garcia yard has two separate production lines. The two brands together cover all relevant applications but each has its own distinct niche:

– Allures for bluewater cruising all over the world

– Garcia Exploration for extreme adventures up to and into the ice

Allures are fitted with a saildrive as standard while the Exploration series, presumably in a nod to the tougher operating environment for which it is conceived (and named), has a conventional shaft drive. Both feature a double rudder system robust enough that the boats can rest on their rudders without damage. The two lines vary significantly when it comes to deck, cockpit and fit-out concepts.

Garcia Exploration yachts are welded aluminium throughout and have a generous amount of freeboard.

Allures yachts have a GRP deck shell bonded flush with the hull. They have less freeboard and are generally regarded as highly aesthetically pleasing.

Allures yachts have a GRP deck shell bonded flush with the hull. They have less freeboard and are generally regarded as highly aesthetically pleasing.

Underwater configurations and material thicknesses are the same for both brands, although there are obvious (if, for example, you ever have the chance to compare the Allures 45.9 and Exploration 45 or Allures 51.9 and Exploration 52 side by side) differences in beam, freeboard and waterline length.

Underwater configurations and material thicknesses are the same for both brands, although there are obvious (if, for example, you ever have the chance to compare the Allures 45.9 and Exploration 45 or Allures 51.9 and Exploration 52 side by side) differences in beam, freeboard and waterline length.

Production numbers are shared openly:

ALLURES

Allures 39.9 / 40.9 2013 – 2021 # 43 built

Allures 45: 2016 – 2022 # 34 built

Allures 45.9 # 30 built so far

Allures 51.9: two under construction, nine on order

Allures delivery time: two years

GARCIA EXPLORATION

Exploration 45: 2013 – 2021 # 40 built

Exploration 52: 2020 – 2021 # 12 built, 24 on order

Garcia delivery time: four years

Escalator clauses have been included in contracts concluded since 2006 due to the long delivery times.

Hamburg 29.01.2022

Peter Foerthmann

FURTHER INFORMATION

Grand Large Yachting

Blue-Yachting