RUDDER, TILLER, WHEEL STEERING, EMERGENCY TILLER

Is overconfidence the order of the day? Have we lost our respect for the forces of nature? Naively succumbed to the marketers’ forked tongue? Is the new really always better than the old? Are today’s boats objectively better than yesterday’s?

Deep down inside, where the flame of personal experience bravely resists the rushing winds of sales-speak and the blustery but hollow protestations of sofa-bound know-it-alls, we know the answer to these questions.

What-if, what-if, what-if? What if we really delved down into all the what-ifs? Less sleep, for one thing! But we sleep easy after all: who has the time to think about the darker side of what may be? Lives are busy and the clock runs faster with every passing year. Sailing brings a much more relaxed pace to life, of course, but with the boat, the sea and the wind competing for our attention we are highly unlikely to give any thought to the potential negatives of our sport – unless fate happens to bring us face to face with them.

Or is our failure to consider what could go wrong actually a conscious decision? Do we in fact hear that inner voice of caution, those unwelcome words of wisdom and actively suppress them? Perhaps we should gird our loins and give our intuition free rein after all. Perhaps it might be worth making time to think about what can go wrong and what we might like to do about it?

I would like to shine a light into these dark places for a moment, to dust off the old mantras and, at the risk of raising the collective blood pressure, to see whether we would not in fact do well to remember the lessons our seafaring ancestors have bequeathed us. Please read:

https://windpilot.com/blog/en/columns/boat-building/what-ever-happened-to-boat-building/

THE RUDDER

The rudder is the soul of the ship. Lose or damage it and reaching any safe harbour in any kind of shape will be a triumph. So wholly reliant are we on this one component that the old-time designers would never have dared to suggest anything even half so vulnerable as a spade or balanced rudder. They liked their rudders tucked away at the aft end of a long keel, where they could be robustly attached along their entire length and were thoroughly protected by the keel, which would reliably bulldoze anything solid out of the way.

https://windpilot.com/blog/en/columns/boat-building/rudders/

However many reasons we might hear to move beyond the old rules and cast off the yoke of past principles in favour of the modern and the new, staying safe at sea ultimately still trumps every other concern. All the sharp theory, clever words and sofa-bound wisdom in the world count for nothing when fate strikes, fear breaks out and physics unshackled takes control.

TILLER STEERING

My predilection for traditional types of boat has its roots in their particular suitability for serious offshore sailing. My special interest of course is in sparing the crew the torment of endless helming, which probably explains why yachts with tiller steering and the rudder solidly hung on the keel or a skeg are for me the brightest stars in the constellation of ideal bluewater steeds.

There are 40-tonne Colin Archer designs with tiller steering that are as light as can be on the helm – a delight to steer for even the most delicate of drivers. The Vikings (not the most delicate of drivers, I think we can assume) steered very substantial boats by hand using solid wooden tillers, along the way giving English the word starboard, among others. And the 2018GOLDEN GLOBE RACEis open only to long-keelers with a keel-hung rudder (all designed before 1988).

Why has what was once regarded as ideal now fallen out of favour in many quarters? Is it simply that boat-building has changed and what was once a craft is now an industry – an industry that has no qualms about jettisoning time-honoured principles if it boosts the bottom line and that has a willing accomplice in the form of revenue-hungry glossy magazines to help it spread its message that the new generally beats the old? Surely not!

I assure you I don’t live in the past, I’m not one for wallowing in nostalgia and I’m positively enthusiastic about innovation, but when it comes to sailing I draw a very clear line between a bit of fun in friendly waters and more serious undertakings far from safe harbour. I believe this line has become blurred in the head of far too many sailors today, partly because it suits them to think that way, perhaps, but also because they lack the knowledge (or good advice) to appreciate the differences. I might be exaggerating to make the point, but… Set off on a long trip with the wrong type of boat and whatever else happens, you will need a measure of luck to come home safe. Set off in the right type of boat, on the other hand, and you need only worry about your own seamanship and the practices of the prudent mariner. Keel and rudder are always the first point to check. A quick glance around the deeper recesses of your own brain should be enough to start you off in the right direction…

WHEEL STEERING

I have always wondered how many sailors prefer wheel steering simply because of the photos: how much more imposing one must look standing at the helm square-on to the world rather than perched on the side-deck clutching a tiller. There are of course also plenty of good reasons one might prefer a wheel. Assuming though that the rudder is properly attached to the keel or skeg, the mechanical wheel steering system is the weak link in the chain: the rudder is operated indirectly and the additional components required as compared with tiller steering (cables and blocks, push rods/gears or hydraulic lines) all represent potential failure points.

Modern cruising boats of the type also thought up, built, sailed and promoted for bluewater use are, however, aligned with a different set of priorities. Many yards buy in mass-produced rudder blades (complete with shaft) and then fit (weld/bond/laminate) them into the hull. Not least because of their carefully profiled and balanced design, these rudders are installed well aft, far from the safety of the keel, and rely solely on their shaft and its mounts and bearings in the hull for survival. Obviously specialist companies with their specialist expertise are able to produce better quality rudder systems at a better price (with more profit for the boat-builder), but a measure of trust is nevertheless required. The vertical separation between the two rudder bearings and the leverage exerted by the rudder blade below raise questions about the ultimate robustness of this approach and such rudder systems certainly cannot be considered the equal of older designs when it comes to safety. The effectiveness of the rudder in performance terms has clearly come to take precedence over strength of mounting and attachment, at least in the context of the ideal solutions described above.

Not surprisingly, almost all of the large-scale boat-builders now choose to procure saildrive units and complete rudder and steering systems from specialist companiesrather than manufacture their own solutions. Presumably the financial benefits are just too significant to ignore. The risks and side effects of this decision are left to the sailor to bear: a spot of water ingress around the saildrive seal or a little “love tap” between a balanced rudder and anything solid will generally suffice to bring the downside of the modern approach into sharp relief.

Provided that nothing gets in the way, containers, fishing nets and other partially submerged solids keep clear, no uncharted shallows or reefs pop up at the wrong moment, the wind and the weather play ball, all on-board systems remain fully functional and the skipper doesn’t leave anything to luck, thousands of joyful sailors will continue to proclaim at top decibel on reaching their destination: “We were fine. It’s all a lot of fuss about nothing!”

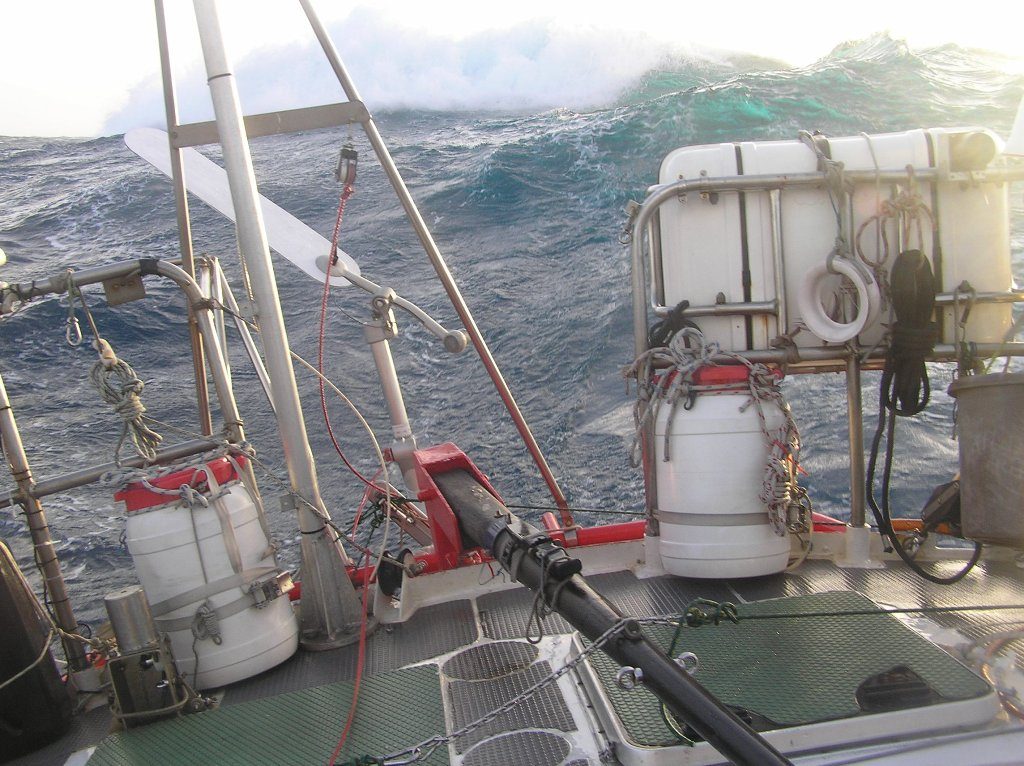

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Credit Pantaenius

Anyone interested in building a more accurate picture of what can and does go wrong could do worse than have a look at the loss statistics produced by the insurance industry. A (more or less) exposed appendage like the rudder is always going to be something of an Achilles’ heel and damage to the rudder, its bearings or other parts of the steering system will tend to have serious consequences, so this is a subject the insurers hear plenty about.

It is quite clear that rudders attached to a skeg and robustly mounted with a third bearing achieve better outcomes in extremis. Even if the lower part of the rudder is lost, enough of the more protected upper part usually survives to provide at least some control.

TREACHEROUS WATERS

My belief that national preferences regarding designs, construction and builders are largely the product of media reporting, targeted marketing through advertisements, orchestrated test reports and boat shows and the observations and recommendations of well-known sailors is thoroughly borne out by the clear differences that exist between countries and continents.

Robustly built traditional types with a long keel and protected rudder are far, far more popular in the USA, for example, than they are here in Europe. I suspect that this is due to the large number of successful American bluewater sailors who have stuck with the traditional model (despite the fashion for “progress” and intensive marketing campaigns promoting a very different type of boat for bluewater use), have found it very effective and have written of their experiences in books that their fellow sailors find credible and compelling.

I have nothing against compromise, at least when compromise becomes unavoidable, but I would have a very limited appetite for compromise in a matter as grave as choosing the right boat for bluewater adventuring. A solid rudder robustly attached to the boat would seem to me an elementary requirement. Am I over-egging the pudding somewhat here? Perhaps I am, but if my efforts are complicating your decision-making process or causing you to revisit past decisions, so be it: ordinary life is all about compromise, but there are different rules at sea and they are not of our making. That’s my view and if you were to call me stubborn for it, you wouldn’t be the first.

German sailors make up a very small proportion of the international bluewater community, but it is still very interesting to compare their choices, in terms of preferred design types, with those of other nationalities.

FURTHER SINS

A large proportion of the boats on long-distance cruising duty rely on a wheel steering system. Presumably few would deny that the transmission components making up such systems constitute a weak point: after all any failure here can have very serious consequences. This leads me to view wheel steering systems – for all that they represent the state of the art for most designs – as another of those compromises I mentioned and, with your kind permission, I have to say they do rank in my mind as something of a minor sin, at least if the boat concerned lacks an effective emergency tiller. Remember the helm is not normally staffed on long trips anyway thanks to that little marvel of engineering that spares bluewater voyagers the purgatory of endless manual steering.

It used to be standard procedure for the main rudder shaft to extend all the way up to deck level, or at least be extendible all the way up to deck level, so that a good, solid emergency tiller could be fitted quickly if necessary to restore proper steering. This had the added bonus in many cases that the windvane self-steering system could be connected to the emergency tiller rather than the wheel to keep the transmission lines short and minimise friction and inconvenience (a win-win if ever there was one). It is still quite common in France to see boats on which the wheel is connected directly to the tiller by lines routed on deck that can be removed (via shackles) when at sea – because humans don’t helm at sea in any case.

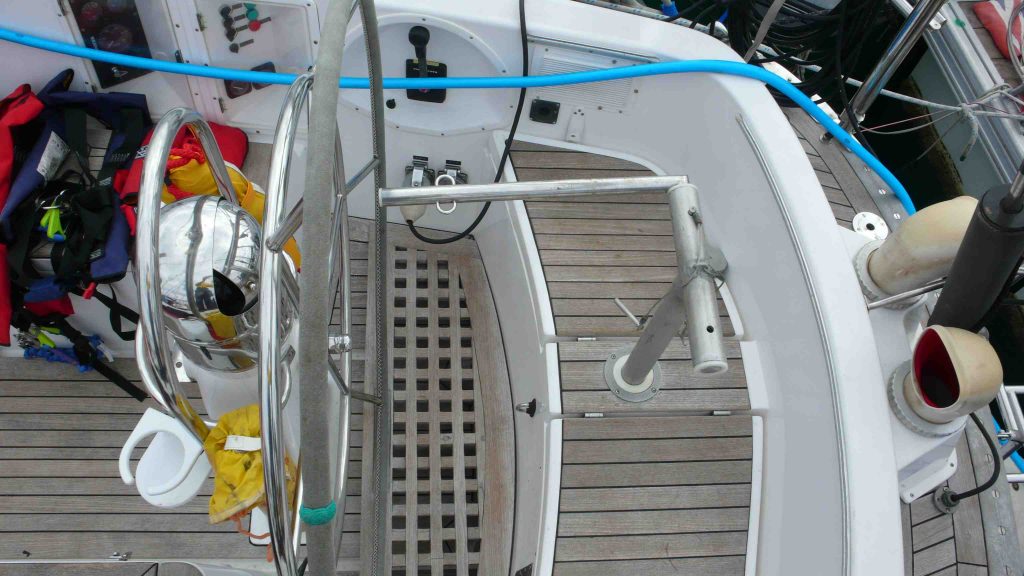

The industrialisation of large-scale boat-building seems to have somehow changed the status of the emergency tiller to the extent that one risks being perceived as a bit of a wet blanket for even suggesting it ought to be robust and effective. It isn’t just concerns about responsibility in the event of an accident that make flotilla organisers so keen on proper emergency tillers: as numerous cases have demonstrated, the difference between an effective emergency steering solution and an ineffective one (or none at all) can be immense. There is certainly plenty of room for improvement in this area, as the photos below show.

Credit: Wilhelm Greiff

Credit: Wilhelm Greiff

Credit: Wilhelm Greiff

Credit: Wilhelm Greiff

Credit: Wilhelm Greiff

Credit: Wilhelm Greiff

Credit: Wilhelm Greiff

Credit: Wilhelm Greiff

I don’t wish to trouble anyone unduly, but in my opinion the standard emergency tillers offered for many mass-produced yachts are just not up to the job of controlling a boat in heavy seas. I consider these half-hearted solutions a sin on the part of a boat-building industry that presumably manages to get away with it simply because sailors are no longer sufficiently aware of the importance of still being able to control their heading if the wheel-steering mechanism is disabled. Astonishingly this matter is barely even discussed in the German-speaking parts of the world despite seeming to feature fairly regularly in English-language publications.

Food for thought!

Peter Foerthmann