PACIFIC LIGHT – DON’T BLAME ME, BLAME BURGHARD

How convenient it must be always to have someone else to blame. I have accumulated quite a list of people on whom I can quite justifiably offload a share; in fact I find recognising who deserves the credit or blame for what can be a useful way of helping to make sense of it all. The what in this case is the Pacific Light.

I have known Burghard for ever. He spent a long (!) time building his orange catamaran Shangri-La on the banks of the Elbe downriver from here and I used to drive past the construction site regularly, never hesitating to pass a disrespectful comment or two on the latest developments. Things went quiet for some years after that as Burghard slowly made his way across the oceans (slowly being the only option with Shangri-La, which was too heavy and solid to make much speed even before Burghard had loaded it to the ceiling with everything discovered and collected along the way for later use ornamenting windowsills, landings, niches, gardens and basements).

The older one grows, the more trinkets and souvenirs one accumulates – in the cupboards, on the shelves, in the garden, just everywhere… It’s a habit not limited to Burghard. Organisation is the critical factor if you want to keep the big picture in view, prevent carve-outs (in the sense of divorce) pruning your assets and be ready and able to tend and care for life’s accumulated objects until you find you can’t safely move around your home any more without falling over them.

Burghard underwent something of a metamorphosis on his return: he didn’t change all that much in himself, I should say, but the arrival of the vivacious Silke as co-pilot by his side (a position she holds to this day) certainly brought a very different complexion to his life. Whatever their secret, the two have clearly found a formula for living every moment to the full as a team.

The lure of adventure soon re-exerted its power over Burghard and before long he – they – started work on the next big idea. And this time it needed to be something properly special. Perhaps it came as a consequence of reading Captain Bligh’s story while under the influence, perhaps not, but for whatever reason, Burghard took it upon himself to re-enact the remarkable voyage that followed the mutiny: the idea of the Bounty Bay was born. Two sloops were quickly cold moulded in wood and epoxy in Estonia (we’re at the end of the 1980s at this point) and then shipped to Lubeck. Why two? Well, Burghard wanted to promote his voyage at boat shows and other events to generate interest – and perhaps entice a sponsor or several – and, practical soul that he is, he felt that would be more easily achieved if he had two boats available.

Then came the moment at which my relationship with Burghard took a more serious turn: might I, he asked, have something light around the place that he could use, a lightweight Windpilot for his two little sloops. And if I didn’t happen to have something already, could I build something? Curiously enough I didn’t happen to have a special lightweight self-steering gear just lying around the workshop, but I found the idea of making one instantly attractive.

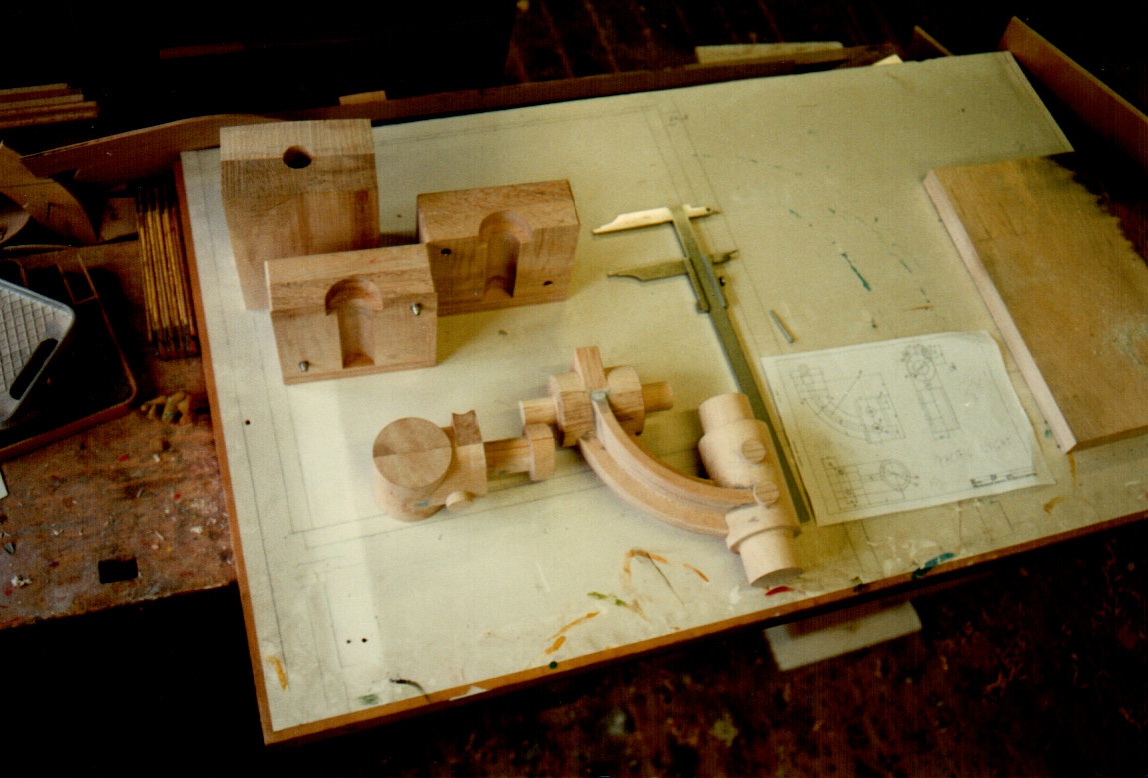

Mr Hoffmann was quickly back at his tools turning out the wooden models for sand casting the aluminium components and the whole initial run of Pacific Light systems (ten in total) was conjured in the space of a few weeks – just in time, as it happened, for us to install one of the new models ready for the Bounty Bay press event. The proud owner particularly wanted to demonstrate the seaworthiness of his diminutive vessel, which could have been a problem given that the venue – Ratzeburger See – was a modest lake in the woods near Lubeck, but by the time he had loaded 17 people aboard a still comfortably afloat Bounty Bay, neither the journalists nor anyone else present had any reason to doubt the fact.

Burghard completed his amazing Pacific adventure singlehanded, with a support boat standing by partly to document the trip and partly just in case. The book he wrote documenting the voyage (which was called “5000 nassen Meilen im Pazifik” in German and doesn’t appear to have been published in English) has, like his other four books, been out of print for many years.

The addition of the Pacific Light to my range, which really did stem directly from Burghard’s prompt, turned out to be a timely move, as the pocket cruiser was then on the cusp of a renaissance all over the world (though that’s a different story for a different day).

Burghard brought another unusual adventure my way some years later. A man with a feel for the mood of the crowd (the bigger the better) and a talent and passion for entertaining, he had the ability to captivate audiences at events – from shopping centres to festivals – with his words while simultaneously convincing them to part with their cash in exchange for home-made jewellery, bottles of mead and other similar wonders.

His tales could transport people to a different world – for example the world of the Vikings (this was an easy one for Burghard, who certainly didn’t need prosthetics or make-up to bring out his inner berserker and often looked as though he might be in between takes as an extra on a film set). The laughter lines on his face left no doubt that this was all great fun for him as well as for his public: a man thriving in the role to which he was born.

Visiting Burghard at his fairy tale house deep in the woods near the Ratzeburger See one day in the 1990s I was struck by the two larger than life moais marking the fairway to his front door. The figures, which had been carved out of giant polystyrene blocks with a saw, were not particularly robust or weather-proof and while they undoubtedly made an eye-catching backdrop for Burghard’s event and trade fair appearances, their size and unwieldiness regularly created a significant logistical headache.

Convincing him of the possibility of making a negative form in GRP from the moais so that we could knock out a full production run of the blockheads turned out to be the work of a few minutes – the idea quickly brought out the inner child in both of us! We made a couple of calls to a team of boatbuilders in Gdansk and before long one of the moais was propped in a trailer heading East. And not so long after that, a trailer holding seven of the giant heads could be seen hurrying back to Germany and Hamburg, generating no end of questions (and featuring in plenty of photographs) along the way. The whole business was nothing but fun from start to finish.

Burghard kept four of the figures and three came home with me. We shared the costs and ended up making no attempt to defray them. The moais had found a place in our heart and became a part of our life – not one of them was ever sold.

Around this time Burghard moved to Lubeck, where he had found an extensive plot of land hosting countless garages and workshop spaces arranged around a spacious home that would have been more than adequate for two families and proved to be perfect for entertaining in style (and enjoying succulent South Seas mussels on the front steps). Formerly host to a tow-truck company, the site had found another ideal proprietor: from the various experiments that inevitably occupy a man like Burghard from time to time to the boating paraphernalia, moai family, fleet of Viking longships and countless other construction projects, there was plenty of space for everything (and still a few spots left over for cars).

The story of Burghard’s adventures is available to read in his own words on hisWebsite nachzulesen. website. Among the armada his habit of acquiring boats has brought him is a mighty catamaran. “Barracuda” was the life’s work of an incessant tweaker and fettler who never had the pleasure of putting his dream ship through its paces on the water. When its builder died, the 17 metre Barracuda came under Burghard’s protection. It made an imposing spectacle, but had more than a few idiosyncrasies too, most notably a large complement of industrial-scale machinery – including twin engines with jet drive (quickly converted to conventional shaft drive) that really merited the attentions of a full-time engineer.

And so it came to pass a few years later that Burghard called me with a friendly enquiry as to whether I might like to take a stake in Barracuda. I already had quite enough experience of fleet management by that time to anticipate the trouble I might be inviting by giving in to such an otherwise tempting offer (I didn’t doubt Burghard’s sincerity, but boats are boats after all) and I regretfully had to say no thanks. Partly this was because I already had a life that was bursting at the seams, my own personal navy to maintain and more than enough excitement to make any thought of boredom laughable; partly it was because I understood my own sense of duty and did not want to drive my gunwales below the water by taking on another responsibility that I would feel bound never to shirk. Better a quick “no” than a “yes” that might put pressure on friendships and generate never-ending consequences.

The result was that Barracuda remained – and remains – a land-bound landmark in search of the kind heart and robust bank balance required to make her seaworthy again.

Burghard had to tackle his most recent adventure, a tortuously long trip on the Pacific with the proa Ana-Varu, without anything Windpilot to embellish his stern. Because he had two of them. Two sterns, that is. I wish I could have come up with something for him when he asked but, tempting as it was to give this or that possibility a try, I could not for the life of me figure out how to fit a vanegear sensibly on a boat on which the two ends are identical and which one counts as bow and which as stern depends on nothing more than the direction of the wind (and changes when the wind or required heading change). The voyage went ahead anyway last year but came to a disappointing end with a mayday call. Skipper and crew all survived unscathed and the press picked up

a nice little story.

A few years ago, Burghard and Silke joined the crew of a cruise ship to share tales of their experiences with tourists yearning for a zephyr of excitement. They proved a success and have now done a number of cruises. Burghard’s repertoire, which encompasses 20 lectures relating to different regions all over the world, makes the most of his remarkable ability to engage and fascinate people with his stories. I can almost see them now, lapping up tales from his catalogue of adventures before retiring replete to their own cruise-ship bunks to lie, half in a dream, replaying the conjured sights and sounds in their own head and imagining themselves riding the oceans in Burghard’s boots.

It must be nigh on the perfect arrangement for Burghard and Silke: working afloat, one of the social highlights of the whole entertainment programme and a well-earned pay cheque (I trust) at the end of it.

When the thought of the Pacific Light first popped into my head, I only pursued the idea for the fun of it. Never did I suspect that in bringing this compact little system into the world I was helping to create a global best-seller.

Don’t blame me, in other words, blame Burghard.

Credit where credit’s due!

Best wishes,

Peter Foerthmann