IN EXTREMIS – LOSING THE RUDDER

It’s dark, very dark, and up isn’t where it used to be. All that time at home on the sofa planning autopilots and windvanes and swaying sun-drenched palms counts for little when you scramble across the cockpit on all fours, place your own now-sweaty palms on the tiller or wheel and discover that there’s nothing left at the other end of the system.

The risk of losing the rudder is one any sailor venturing far from land should take proper time to consider. How can we minimise the chances of it happening and how would we cope if it does? As ever, there are good and bad answers to both of these questions and sound advice is the key. Preparation always beats regret!

Sound advice on rudders can though be hard to find: the usual self-proclaimed oracles have little to offer on the subject and the manufacturers’ glossy brochures and media test reports are seldom any better. Why? Because in a world where sales and margins are the ultimate arbiter of all matters, questions about rudder safety are an inconvenient intrusion and because there are no shortcuts to acquiring expertise. Some things cannot be bought and the life experience that breeds expertise is one of them.

IN EXTREMIS – PULLING NO PUNCHES

I understand that not everyone enjoys pondering the bad things that can happen at sea but personally I find it fascinating, not to mention worthwhile, to do exactly this (and, having done so, to share the results). You can review my previous efforts in this direction in two other articles

I know my segment of the market like I know my own coat pocket thanks to a long and eventful history in the transom ornamentation business (I have shared the full gory details elsewhere, so an ultra-brief summary will do here). I have manufactured all of the different system types, from the early auxiliary rudder and servo-pendulum systems to the current Pacific and Pacific Plus sister models. I modernised and expanded the range in 1998, since when Windpilot has been offering the following modular line-up, all produced using advanced industrial manufacturing methods:

PACIFIC LIGHT, a servo-pendulum system for boats under 29 feet

PACIFIC, a servo-pendulum system for boats under 70 feet

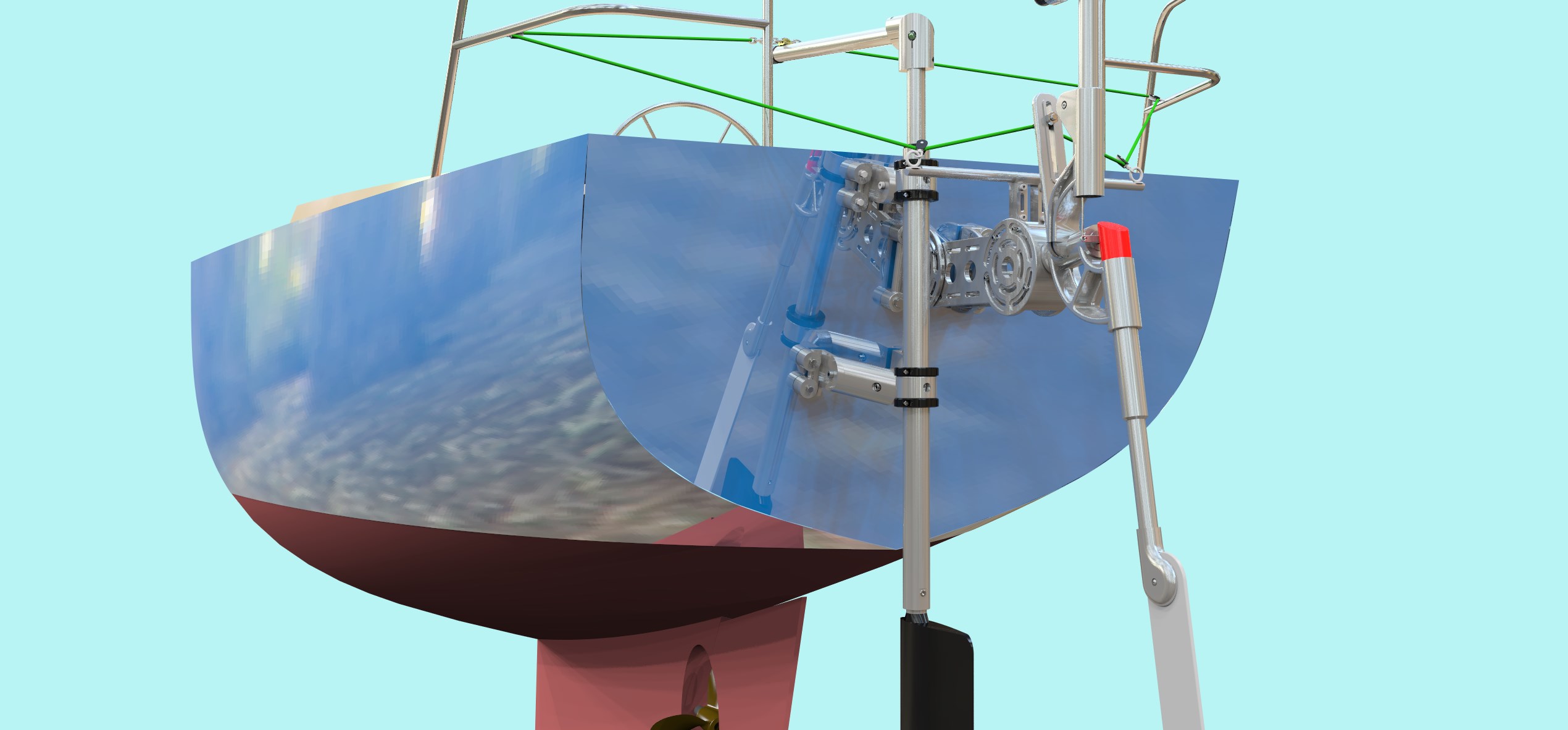

PACIFIC PLUS, a double rudder system for boats under 60 feet

SOS PACIFIC, an emergency rudder available as an upgrade to the Pacific

SOS SOLO, an emergency rudder for non-Windpilot boats

Building Windpilot has been something of a labour of love and my enjoyment of the business extends to seizing every opportunity to refine and upgrade my products and generally realise any potential improvements I can identify. It’s an approach that has seemed to work so far and while I am aware of the dangers of overconfidence, I have also come to accept that a sprinkling of Narcissism is probably a helpful thing to have in life. Similarly, rather than fume and rage over the way that various technical features of my designs have been “emulated” by others around the world, I have learned to regard it as a welcome confirmation and endorsement of the Windpilot design philosophy. I discuss my views on the subject of copyright and copycat designs elsewhere. What concerns us here and now is the subject of emergency rudders.

EMERGENCY RUDDER OPTIONS

The worst has happened and the rudder is damaged, out of commission or just nowhere to be seen. What next? US magazineSAIL in den USA recently published a detailed report on the options here

THE SOS RUDDER – PROTOTYPE FOR SV SUBEKI

I designed what became the prototype of Windpilot’s SOS Rudder product for SV SUBEKI in 1999 at the request of owners Sybille and Christian Uehr. The Subeki crew built the first actual device off my drawing for themselves on the dock at Las Palmas and it gave them great peace of mind on their circumnavigation from its sentry post by the stern rail.

It is a wonderful – and thankfully not too uncommon – sensation to realise that a few words from a fellow sailor have set the cogs whirring again and gifted me a head full of ideas just itching to be turned into practical solutions. Thanks Sybille and Christian!

THE GOLDEN GLOBE RACE

I find it most interesting that the GGR has started to pay such a lot of attention to the subject of emergency rudders. There is nothing unusual about having one’s curiosity piqued, of course, but sometimes that little germ of an idea that sets the thought processes in motion acquires extra vigour by virtue of having such an unexpected origin.

What started me thinking in this instance was Don McIntyre’s rulebook for the GGR. Generally, the rules for this demanding solo non-stop race are very specific – so much so that establishing compliance has proven to be a significant financial hurdle among less well funded candidates for the fleet. Windvane steering systems are relatively lightly regulated, but the rules are very clear that every participant must have a fully-functional emergency rudder. And when the rules say it has to be fully-functional, they mean it: every participant must provide video evidence demonstrating the presence and effectiveness of an emergency rudder system. Now at first glance this just seems like a responsible step to take to increase safety at sea, but the more I thought about it, the more I became aware that there was another side to it altogether. Which is what prompted me to sit down at the keyboard. Before I say any more on this, let me add a few – not necessarily unrelated – words on the subject of sponsorship.

SPONSORING

Hunting for sponsors is a big part of the job description for an event organiser. Sponsorship helps to shift some of the financial burden onto other shoulders, reducing the organiser’s own investment and improving its chances of making a profit out of its venture. The carrot for sponsors, the proposition that parts them from their cash, is global media exposure (depending on the scale of the event) and the associated opportunity to polish their brand and implant it in the mind of event fans, who are then expected to adjust their spending habits to make the whole exercise worthwhile.

Credit Antoine Cousot

Don McIntyre has apparently found it difficult to drum up much interest among potential sponsors for the GGR. The question of why that should be the case can wait for another day, but Don’s announcement that he will bankroll the event out of his own pocket if necessary strikes me as a thoroughly honourable gesture and a clear indication of just how much he cares about the race and its participants (seehere for more on the subject from the man himself).

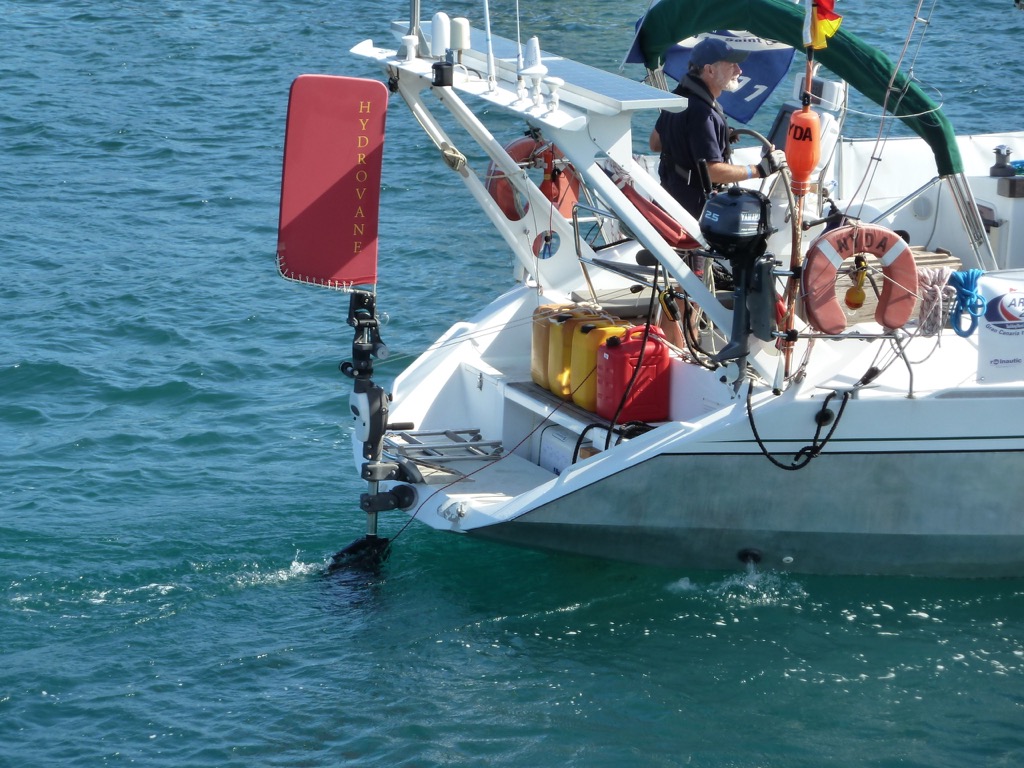

DON MCINTYRE AND HYDROVANE

I have found myself giving considerable thought to the GRR of late, especially the business model of a sponsor partnership between the organiser and one of my fellow operators in the windvane steering business. If a sponsor chooses to invest in an event as a way to raise the profile of its brand, it is a safe bet that the associated costs are already factored into the price of its products. The cost of the sponsorship arrangement, in other words, is met by all consumers, existing and new, who are drawn to the brand concerned.

The idea is that this produces a win-win situation in which the brand becomes conflated with the event and its drama and prestige in the mind of consumers, who consequently flock to the checkout, credit cards at the ready. It works too: just look at what we wear, drive and eat. But then look at the water. The global marine business is small fry and, a few top races and foil-assisted record attempts aside, it just doesn’t have the scale or traction to support the type of marketing concepts employed in other sporting arenas (and leisurely cruising – for obvious reasons – certainly doesn’t tick the sponsors’ boxes).

I wouldn’t want to speculate about the level of investment committed by my counterpart but it is quite clear we share what is very much a niche market. All of the companies involved in the windvane business are small organisations with modest sales, so it is not immediately obvious to me just what this investment is intended to achieve. Oddly, it appears in the case of the GGR that the sponsor of the event may be recouping at least a portion of its investment directly from the pocket of the people participating in the sponsored event. That would be sponsorship eating itself, wouldn’t it? Imagine Formula 1 drivers being expected to pay their sponsor for the spoiler on the back of the car…

I do hope this doesn’t sound like envy or jealousy talking: my views on sponsorship have been in the public domain for a long time!

THE CART BEFORE THE HORSE

If, as appears distinctly possible, the sponsor entered into this particular agreement primarily to gain exclusive access to the participants, how does this serve the sailors – the stars of the event? The sailors may feel obliged in some way to support their event sponsor and the organiser (who has quite naturally endorsed his sponsor’s product) may well be happy for them to feel this way, but in the end it is they who have to foot the bill (and deal with the consequences should it transpire that the sponsor’s product is not the best fit for their campaign).

The organiser’s insistence on a fully-functional emergency rudder (“as long as you can show you can fit it in a seaway”) strikes me as perfectly understandable but, putting aside my personal reservations about sponsorship in the windvane steering business for a moment, I have to say that I find the logic of the GGR/Hydrovane agreement difficult to follow – not least because of the obvious contradictions between the broader aims of the organisation and the apparent aim of the deal.

DELIBERATION AND INSPIRATION

A number of GGR sailors have been in touch with me – electronically or in person – over the last few months to discuss issues associated with the race and seek my technical advice. I find it particularly rewarding to see suggestions I have made put into practice (something I definitely cannot take for granted these days). Eventually I found I had developed a sufficiently strong bond with several of these people to feel confident offering them a little direct assistance: I have the greatest respect for the sailors willing and able to put themselves on the GGR start line and it is a pleasure to be able to help a few of them chase their dreams. I am of course more than happy to share my experience and opinions with any of the participants; they only have to ask (no cold e-mail here).

Where our discussions have touched on self-steering (not an uncommon occurrence), I have suggested that my Pacific Plus system is probably not the best choice given the type and size of boat being used and the importance of saving weight wherever possible. A powerful yet lightweight servo-pendulum system seems to me the only sensible option on craft like these with the main rudder close at hand. It has come to my attention (largely indirectly) that one or two of those I discussed the matter with eventually decided to go with my competitor’s product. Which is fine.

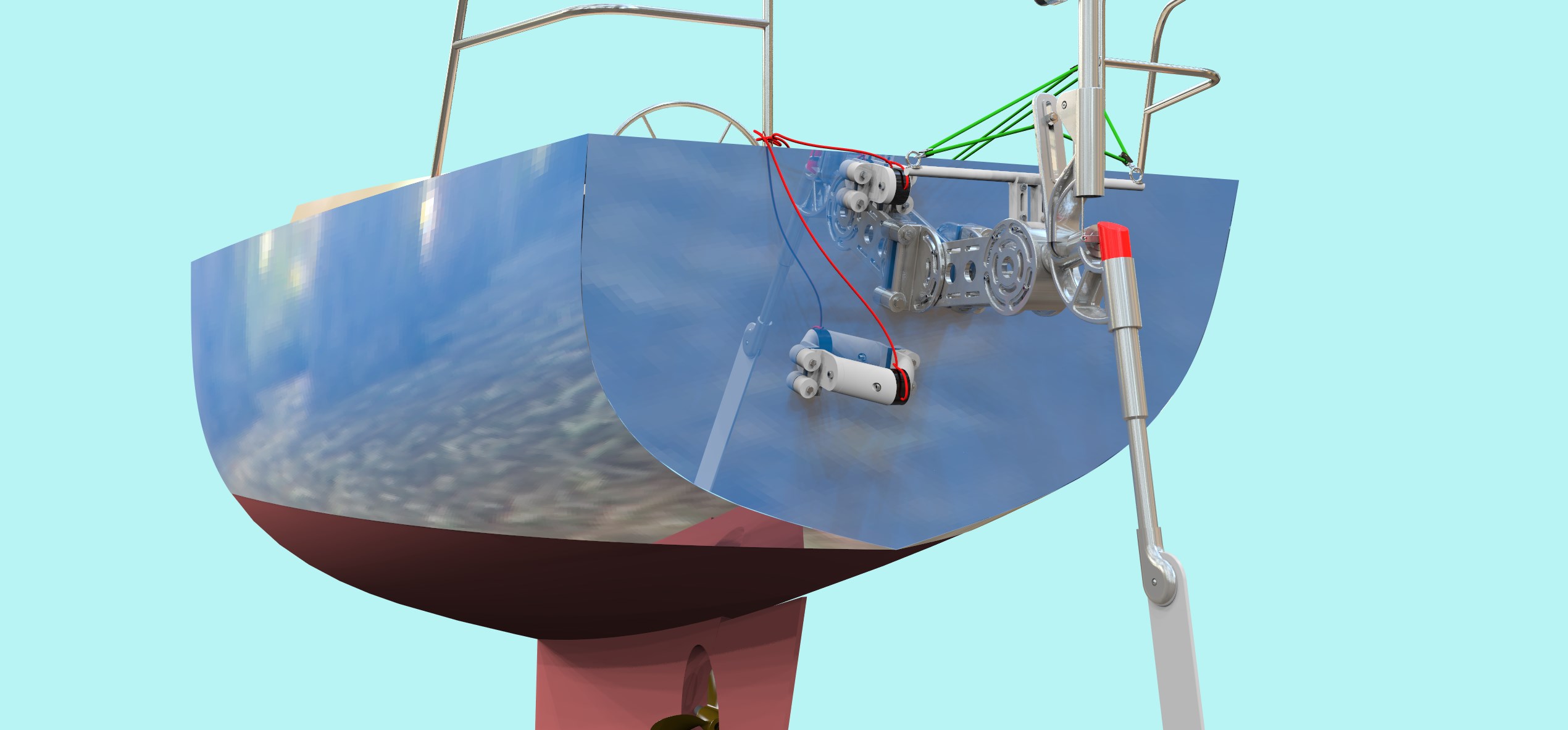

By the time I met up with Igor Zaretskiy in Paris in December 2017, it had become quite clear that the organiser would not be softening its interpretation of the emergency rudder rule and with this in mind I confirmed that I would indeed be prepared to supply one of my SOS Solo emergency rudders.

THANK YOU DON

Now, I admit it did initially cross my mind that this strict emergency rudder rule could be a good way of generating a bit more of a return for the event sponsor, which happens to sell an emergency rudder system. Luckily though the thinking didn’t stop there. I was aware that Ertan Beskardes had added a Hydrovane to the existing Sea Feather servo-pendulum system on his Rustler 36, presumably in response to this rule. Might this, I wondered, mark the start of a fleet-wide rush to fit a second windvane steering system?

credit Ertan Beskardes

Would the fear of falling foul of the rules eventually lead to boats with three rudders (main rudder, servo-pendulum system and auxiliary rudder system)? I don’t for a moment suppose that this is what Don had in mind, but once the idea had sparked in my head I had to see it through.

SOS – SOLO – PACIFIC

My deliberations led me to conclude that I might actually have a previously unsuspected gap in the Windpilot range and I consequently decided to produce a third version of the SOS emergency rudder for the GGR.

Here are the three options now available:

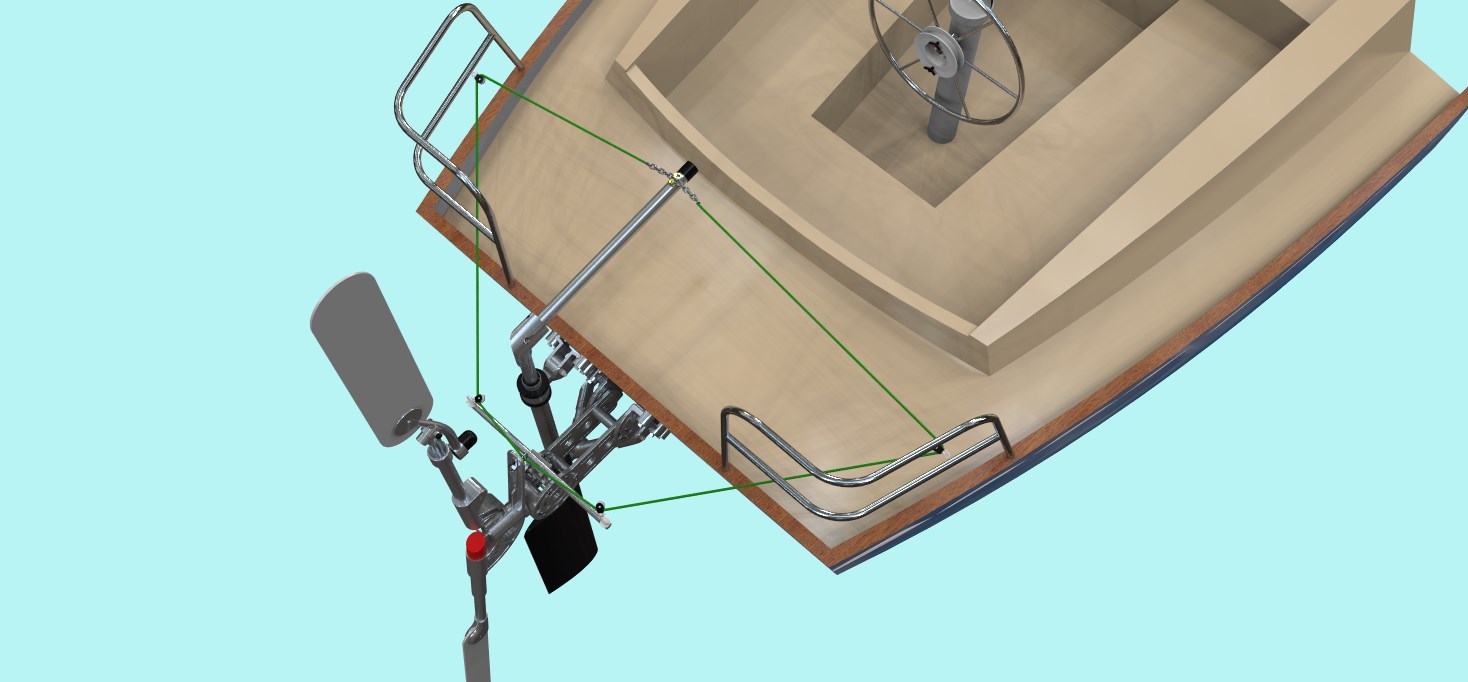

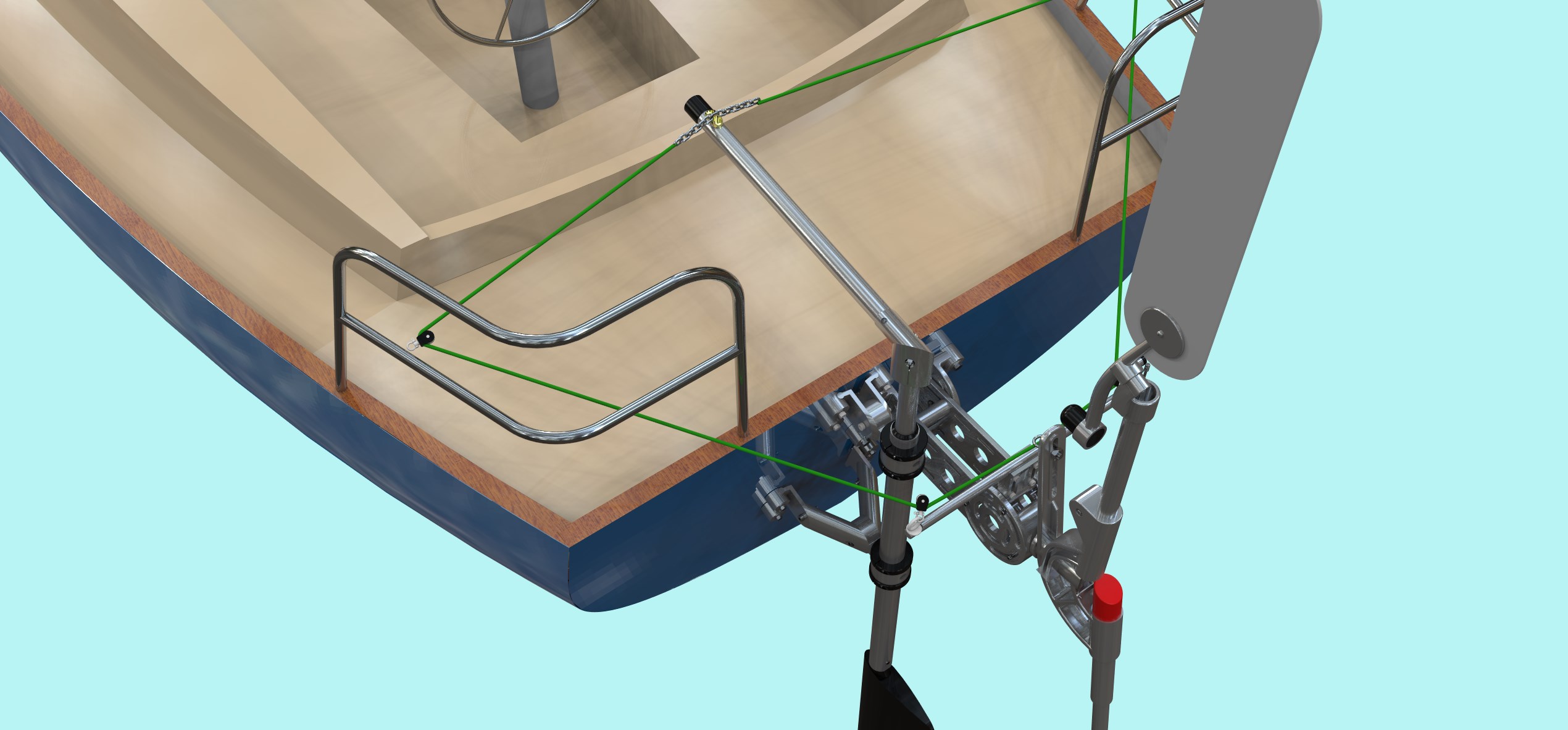

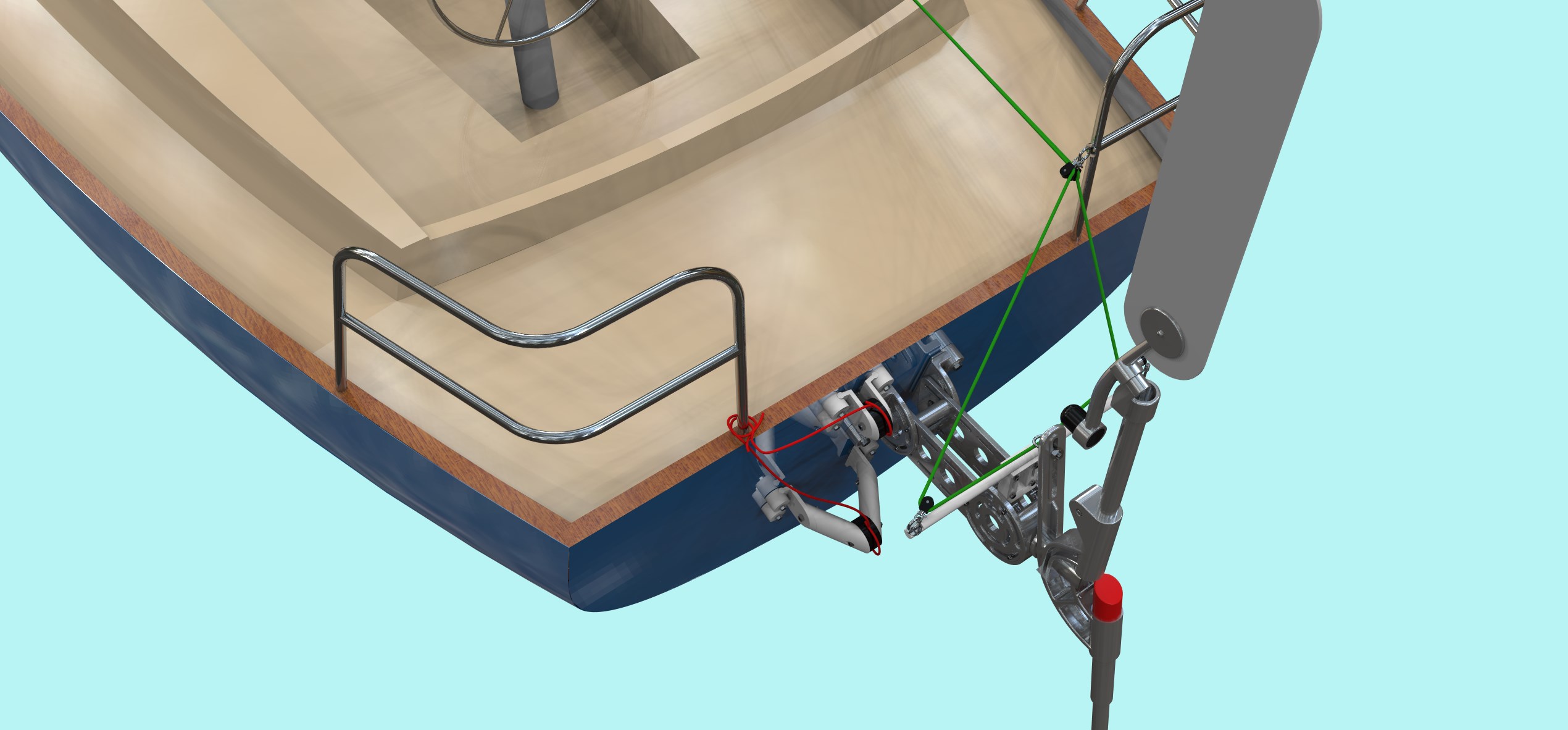

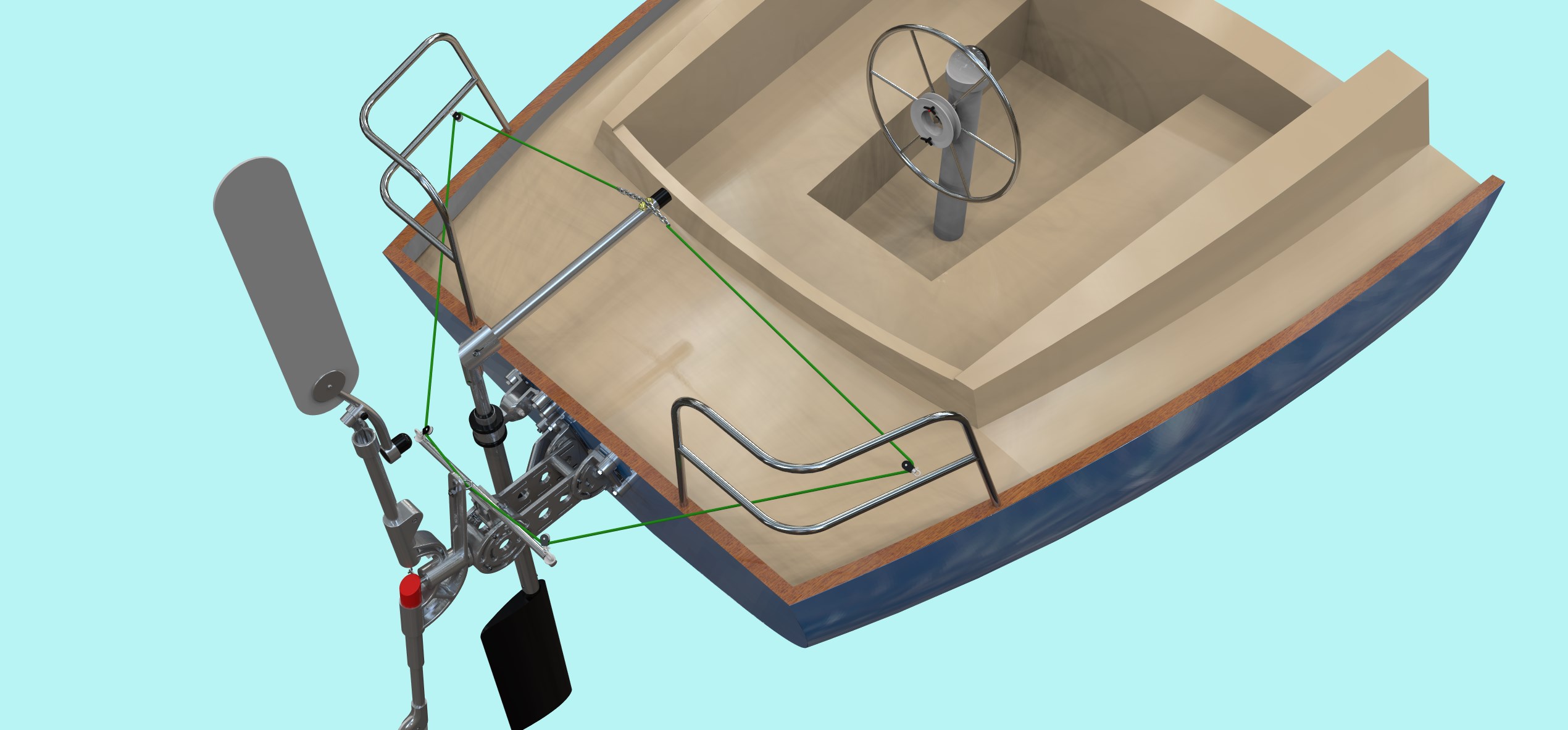

SOS PACIFIC – an emergency rudder system to be fitted on existing Pacific mountings; designed to be stored in a bag in a cockpit locker until needed.

SOS SOLO – a transom-mounted emergency rudder system for non-Windpilot boats; designed to be stored in a bag in a cockpit locker until needed.

SOS SOLO PACIFIC – a hybrid system in which the emergency rudder component (once retrieved from its storage bag in a cockpit locker, obviously) can be connected to the Pacific component to create an emergency double rudder system.

The advantages of the powerful combination of auxiliary rudder and servo-pendulum rudder technology are well known, so the SOS Solo Pacific seems like the logical step to give participants effective self-steering even in an emergency.

This is my response to the challenge, a reconfiguration of my existing modular system line-up that I would never have stumbled across without the stimulation of a challenging set of rules and the urgent questions of the sailors racing to master them. Thank you, Don, for drafting the rule that set me thinking!

I mentioned in my opening remarks the importance of preparation. Let us hope that the preparation phase is the last time any of our GGR skippers has to give any serious thought to emergency rudders and that none of them has to put their plans into practice during the event.

That will be all for today.

Peter Foerthmann