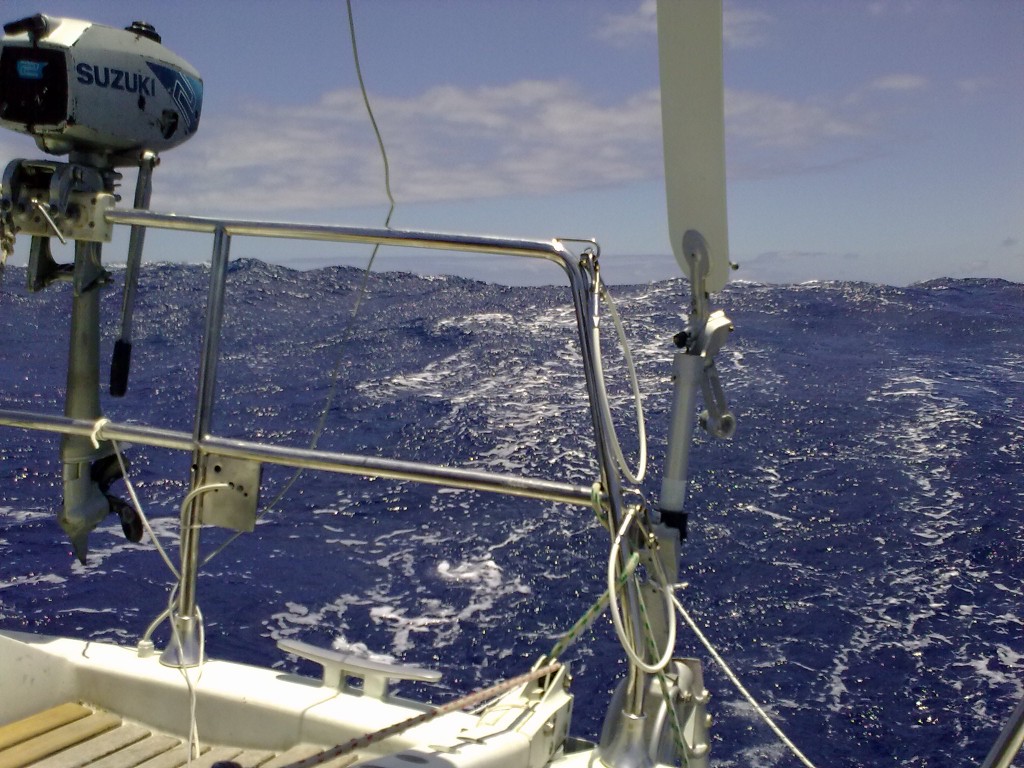

SV Jöke, a german built Phantom 38, on her way around the world… for 8 years

Mit Spi über die Nordsee und die Windpilot hält Kurs!

Wibo 945 with Windpilot Pacific, please follow her blog here

April – May – conversion winter to summer

Barbeque not ready yet – still deep winter – eventhough spring is around the corner

Working on deck is possible – outside however – not

Decks hardware prepared for hard work

Some confusion on deck and around – too many other boats – at least

A bit of cleaning – quickly done…

Underwater Icebergs need some paint and upgrade

Dreaming about working at boats is slightly different rather than the work itself…

Dreaming about Kobenhagen – perhaps the trip of this summer?

Spring is in front of any door – sometimes not really

At least the Captain is prepared for his duties…

As the crew nearly always is…

All safety equipment in good working order

And the blind passenger ready for new challenges – even on a move

SV Gwen, Alain Guennou FRA

Dear Peter,

as I promised some 17 years ago, I send you the pictures of the installation WINDPILOT PACIFIC 1994, on my new sailing boat ALUBAT OVNI30.

The system is working very well, like usual since 1994 on my former boat.

But, I have a little problem with the DELRIN bearing part #75, because since 1994 when I am not on my boat, I have the used to remove the rudder fork and the windvane shaft, for to avoid damage by other boat in the marina on a river with strong flood, so after 17 years of UV sun exposition this part #75 is destroyed leaving in dust. Now I put a little bag for to protect from the sun, but it’s too late.

But, I have a little problem with the DELRIN bearing part #75, because since 1994 when I am not on my boat, I have the used to remove the rudder fork and the windvane shaft, for to avoid damage by other boat in the marina on a river with strong flood, so after 17 years of UV sun exposition this part #75 is destroyed leaving in dust. Now I put a little bag for to protect from the sun, but it’s too late.

So can you send part #75. Thank you in advance.

Best regards.

Alain GUENNOU

SV Swantje, Rainer Wäsch GER

Hallo Herr Förthmann,

nach der viel zu langen Winterpause habe ich am Mittwoch 27. April mit Unterstützung von Vereinskameraden endlich die erste Fahrt mit der neu installierten Windpilot Pacific unternommen.

Kurz gesagt: Für´s erste bin begeistert !

Hier als “Dankeschön” ein von mir produziertes YouTube-Video:

EMKA29 mit Windpilot Pacific

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QS4oVeucP6g&feature=player_embedded

welches ich auf meiner Homepage eingebunden habe.

Auf unserem geplanten Norwegentörn mit Swantje gelingen mir unter Umständen noch ein paar spektakuläre Aufnahmen im Zusammenhang mit der Pacific.

Bis dann…

Mit bestem Gruß

Rainer Wäsch

SV Pjotter, Martha + Kees Slager NL

We got a message from our friends in America that they have received a spare part from Windpilot. Thank you very much for sending this part. Your service is excellent!

I have made some pictures of the windpilot but without the new spare part. When I have the new spare part ( half May) then I can make new pictures. The pictures we can’t send to you because we have not good internet in this part of the world where we are sailing now. We have been in Colombia, Panama and Costa Rica and yesterday we arrived in Cuba. As soon as we have good internet we will send the pictures to you.

We also have a blog where we describe the adventures and stories of our trip.

Here is the site of SV Pjotter

Thank you very much again. I am very satisfied with my windpilot.

Kind regards from Kees Slager SY Pjotter a BREEHORN 44

SV Janila, Jochen Beusker DE

Blauwassergeeigneter Stahlbau GLACER 40 mit hydraulischem Schwertl ist nach vom Erstbesitzer und Erbauer zu verkaufen. Hier sind die Details

Blauwassergeeigneter Stahlbau GLACER 40 mit hydraulischem Schwertl ist nach vom Erstbesitzer und Erbauer zu verkaufen. Hier sind die Details

SV Jessamy, Roderick Innes, UK

After sailing his beloved SV Jessamy, a RUSTLER 36, Roddy handed his boat over to some friend. One of them Jeremy Cobban contacted me some time ago:

After sailing his beloved SV Jessamy, a RUSTLER 36, Roddy handed his boat over to some friend. One of them Jeremy Cobban contacted me some time ago:

Peter,

Having sailed a friends Rustler 36 “Jessamy” with your excellent self steering gear for many years, a group of us wish to show their appreciation of the owner’s generosity by having a 1/2 hull model of it made to present to him. I have a man to do the model and the boat drawings but need details of the windpilot, presumably a Pacific, to make the model specific and authentic. Problem, the boat is laid up with only the bracket visible and I don’t want to alert the owner to our plans by asking him to fish out the vanes etc to get measurements. Have searched my photos but nearly all from the boat not of the boat with it rigged. Is it possible you have a simple sketch/drawing, if not dimensioned, from which I can take approximate dimensions? I cannot praise the performance of your product too highly on every point of sail and all weathers, even with spinnaker up and a quartering sea though being a long keel tiller driven boat does help! A sales blurb with dimensions of the vanes would be ideal. Email or mail to Jeremy Cobban, Fernhill Farmhouse, Mill Lane, Titchfield, Hants. PO15 5RB

SV Otter II, Marjo+Jean Lumaye BE

SV Maus, Manfred Marktel ITA

A compliment to the sea from Manfred whilst longterm restricted to Italian Hospital. His beloved boat SV Maus is being cared in Brasilian waters from close friend in that lovely country.

A compliment to the sea from Manfred whilst longterm restricted to Italian Hospital. His beloved boat SV Maus is being cared in Brasilian waters from close friend in that lovely country.

YACHTING WORLD, Atlantic Gear Test, Windpilot top rated

If you’re thinking about equipping your yacht for long-distance cruising, our unique annual Atlantic Gear Test, the largest independent test of marine gear in the world, is invaluable. In the first of a two-part special feature, Toby Hodges reveals the results of

If you’re thinking about equipping your yacht for long-distance cruising, our unique annual Atlantic Gear Test, the largest independent test of marine gear in the world, is invaluable. In the first of a two-part special feature, Toby Hodges reveals the results of

a survey of 220 boats in last year’s ARC

Two hundred and thirty three yachts from 26 different countries set off on the 25th Atlantic Rally for Cruisers (ARC) last November. Not only was this an impressive gathering in Las Palmas for the start, it also furnished Yachting World with over 220 completed ARC Survey forms to create our annual Atlantic Gear Test, the world’s largest independent test of marine gear.

A collective total of over 660,000 nautical miles of ocean sailing by these boats and their crews put equipment through the most comprehensive of roadtests, and feedback from previous Gear Tests shows how valuable this resource is to owners equipping their boats for an ocean crossing or any long passage in the future.

So this year we are reporting even more fully on the results and dividing the feature into two parts. This month we examine equipment that falls under the heading ‘Mechanics and Machinery’, from autopilots to watermakers, before going on to look at ‘Electronics and Sails’ next month.

How the Gear Test works

Every ARC entrant is given a six-page survey to complete and hand in at the finish in St Lucia. We ask them about equipment currently on the market and to rate it 0–5 (‘Useless’ to ‘Superb’) for three different categories: Reliability, Ease of Use, and Value for Money.

Skippers and crews are also asked to add comments on the performance of each item, which helps us ascertain why certain products excelled and others failed to live up to expectations.

In order to ensure that the results are statistically viable, we can only include products that have been carried by at least four boats on the Atlantic rally.

Please read the Atlantic Gear Test ARC survey pt 1

What ever happened to boat building? Part 3

Boatbuilding and the market

Once more into the breach!

The only way to be sure a boat is really robust and well-built enough for long-term use is to put it to long-term use – or break it trying… However the typical year for most seafarers yet to shed the shackles of the rat race amounts in total to no more than a few weeks under sail in a good year and less than a hundred hours on the engine in a bad year: most boats spend most of their time turning silent, solitary circles around a mooring buoy or staring at an empty car park in the vain hope that today, at long last, the skipper will finally put in an appearance and let them off the leash.

I wouldn’t want to put an exact figure on the number of nautical miles required to reach a verdict, but I do think considering the relative merits of different boats in long-term use is a good way of establishing the criteria that really count in practice. It is self-evident that yachts used for bluewater voyaging have to withstand far greater loads than fair-weather weekenders. Strongly tidal waters and the higher latitudes also have their challenges I concede, but we cannot penetrate to the heart of the matter without considering proper long-term offshore exposure.

I wouldn’t want to put an exact figure on the number of nautical miles required to reach a verdict, but I do think considering the relative merits of different boats in long-term use is a good way of establishing the criteria that really count in practice. It is self-evident that yachts used for bluewater voyaging have to withstand far greater loads than fair-weather weekenders. Strongly tidal waters and the higher latitudes also have their challenges I concede, but we cannot penetrate to the heart of the matter without considering proper long-term offshore exposure.

A design’s ability to hold its value over time is a key indicator here: any owner whose boat is known to have come up short in the moment of truth can expect to see its resale value evaporate like sea spray on a hot day in the Canaries. Boats become permanently unsalable if the nautical community gets wind of any serious weaknesses.

A design’s ability to hold its value over time is a key indicator here: any owner whose boat is known to have come up short in the moment of truth can expect to see its resale value evaporate like sea spray on a hot day in the Canaries. Boats become permanently unsalable if the nautical community gets wind of any serious weaknesses.

Obviously the yachts we turn to as the vehicle of our sailing fantasies in generally show far more endurance than their crew. When conditions deteriorate, the great majority of sailors head straight for the nearest port, teeth clenched, without ever giving the storm sails a chance to shine. The more unpleasant memories tend to fade quickly, especially away from the water, and soon enough bad times have been reborn as great stories and it’s time to get back afloat. This, of course, is all part of the charm of our sport, but it does nothing to alter the fact that most boats are only very seldom really put to the test. While this may be good for the manufacturers (nobody likes complaints), it does increase the risk of sailors only discovering the true limitations – and absolute limits – of their vessel once it is too late to find an easy way out.

Obviously the yachts we turn to as the vehicle of our sailing fantasies in generally show far more endurance than their crew. When conditions deteriorate, the great majority of sailors head straight for the nearest port, teeth clenched, without ever giving the storm sails a chance to shine. The more unpleasant memories tend to fade quickly, especially away from the water, and soon enough bad times have been reborn as great stories and it’s time to get back afloat. This, of course, is all part of the charm of our sport, but it does nothing to alter the fact that most boats are only very seldom really put to the test. While this may be good for the manufacturers (nobody likes complaints), it does increase the risk of sailors only discovering the true limitations – and absolute limits – of their vessel once it is too late to find an easy way out.

We could of course turn a blind eye to stories of trouble at sea, keep our thoughts within our comfort zone and specifically avoid learning just what can happen in extreme conditions. This approach, I would suggest, is likely to be more popular among those who have reason to fear their own judgment: it cannot be a nice feeling to buy a boat for one set of reasons and then fall out of love with it on other, far more compelling grounds.

We could of course turn a blind eye to stories of trouble at sea, keep our thoughts within our comfort zone and specifically avoid learning just what can happen in extreme conditions. This approach, I would suggest, is likely to be more popular among those who have reason to fear their own judgment: it cannot be a nice feeling to buy a boat for one set of reasons and then fall out of love with it on other, far more compelling grounds.

The matter of hull strength we have already done to death and there is nothing to be gained be revisiting it. But what about keel, rudder and engine? A saildrive, for example, which leaves the crew parted from the fishes by just a few millimetres of gasket, can prove the Achilles’ heel of an otherwise robust yacht. Saildrives have insidiously worked their way aboard all kinds of designs now thanks to the fact that they are much quicker for the yards to install, but they remain a matter of concern among insurers and have proven by and large to be a retrograde step in the long run for us sailors.

The matter of hull strength we have already done to death and there is nothing to be gained be revisiting it. But what about keel, rudder and engine? A saildrive, for example, which leaves the crew parted from the fishes by just a few millimetres of gasket, can prove the Achilles’ heel of an otherwise robust yacht. Saildrives have insidiously worked their way aboard all kinds of designs now thanks to the fact that they are much quicker for the yards to install, but they remain a matter of concern among insurers and have proven by and large to be a retrograde step in the long run for us sailors.

Here too the new ‘solution’ fails to measure up to the older ideas it has replaced: commercial shaft drive systems always include a thrust block to pass on the thrust from the shaft, but force transmission in a saildrive system is inherently unfavourable because of the way thrust generated in the basement has to be tamed and transferred a whole level higher up in the structure. This is quite different to the situation with a conventional drive, which transmits its propulsive force to the backbone of the vessel in a straight line and, of course, enjoys a protected location tucked in at the trailing edge of the keel. The difference in terms of the work involved in installation and alignment between a conventional shaft system and a saildrive amounts to many hours – too many hours for the major production boatbuilders to ignore. For sailors, however, the case is not so clear cut: while a leaking stern tube is certainly annoying, it is nothing compared to some of the problems encountered with a saildrive.

Here too the new ‘solution’ fails to measure up to the older ideas it has replaced: commercial shaft drive systems always include a thrust block to pass on the thrust from the shaft, but force transmission in a saildrive system is inherently unfavourable because of the way thrust generated in the basement has to be tamed and transferred a whole level higher up in the structure. This is quite different to the situation with a conventional drive, which transmits its propulsive force to the backbone of the vessel in a straight line and, of course, enjoys a protected location tucked in at the trailing edge of the keel. The difference in terms of the work involved in installation and alignment between a conventional shaft system and a saildrive amounts to many hours – too many hours for the major production boatbuilders to ignore. For sailors, however, the case is not so clear cut: while a leaking stern tube is certainly annoying, it is nothing compared to some of the problems encountered with a saildrive.

Class association publications and resources can be an excellent point of reference when trying to assess the long-term qualities of production yachts, as they describe known weaknesses and solutions and can provide useful tips to help owners make the most of their investment (here are some links to well-known owners’ associations, some of which enjoy almost legendary status among the cognoscenti:

Contessa 26; Contessa 32; Westerly; Sadler; Hans Christian; Hurley; Moody; Island Packet; Valiant; Cape Dory; Westsail; Bristol; Cheoy Lee; Passport; Corbin; Hallberg Rassy; Najad; OVNI). Just about every reputable brand operates an Owners’ Association (albeit a few find the temptation to use it mainly as a marketing platform for new models hard to resist).

The Contessa 32 occupies a special niche in the used boat market thanks to its exceptional build quality. Take an example with a lifetime of use (30 to 40 years in many cases) already behind it, send it for a full refit with the original builder and you have a boat as good as new ready for another lifetime of adventures. Yachts like this hold their value and represent a good investment for their owners. The same cannot be said at the moment for many of the more common modern production yachts, whose resale prices are seriously compromised by the sheer volume of options available in the second-hand market. As elsewhere, market activity and prices depend on the balance of supply and demand, with excess demand pushing up prices and enabling sellers of the most coveted models to walk that little bit taller on the way to the bank. If there are more sellers than buyers (say, for example, the market becomes flooded with retired charter yachts), however, boats will only sell, if at all, at a substantial discount.

The Contessa 32 occupies a special niche in the used boat market thanks to its exceptional build quality. Take an example with a lifetime of use (30 to 40 years in many cases) already behind it, send it for a full refit with the original builder and you have a boat as good as new ready for another lifetime of adventures. Yachts like this hold their value and represent a good investment for their owners. The same cannot be said at the moment for many of the more common modern production yachts, whose resale prices are seriously compromised by the sheer volume of options available in the second-hand market. As elsewhere, market activity and prices depend on the balance of supply and demand, with excess demand pushing up prices and enabling sellers of the most coveted models to walk that little bit taller on the way to the bank. If there are more sellers than buyers (say, for example, the market becomes flooded with retired charter yachts), however, boats will only sell, if at all, at a substantial discount.

A few minutes in the company of Google and the usual portals can give a pretty good idea of the market value of used yachts (although it should not be forgotten that there can be a big gap between asking price and actual selling price and selling prices hardly ever become public knowledge). That today’s market is a difficult place even for high-quality yachts from respected yards is evident from the way so many pre-owned examples take such a long time to find a new home. The classifieds pages of leading sailing magazines contain innumerable repeat ads, with boats commonly taking several years to sell despite being advertised with good photos and plenty of detail. Brokers have no magic power to speed up the process either – in fact there is often little they can do other than add yachts to their own listings and advertisements.

And yet craft from certain yards still seem to sell with ease. Second-hand KOOPMANS yachts, for example, regularly command excellent prices – irrespective of hull material – and are commonly snapped up almost as soon as they become available. OVNI, GARCIA, BESTEVAER, VAN DE STADT, HUTTING and other aluminium yachts also often seem to change hands quickly with little fanfare at a price strong enough to spare seller’s blushes. The stand-out performer among the GRP builders meanwhile is BREEHORN, whose Koopmans-designed boats are purchased almost exclusively by private buyers and are in most cases used for long-distance and offshore sailing. Their seakeeping, construction and robustness have elevated Koopmans yachts in the European market to a position similar to that once occupied by Sparkman & Stephens.

A good reputation, which boosts resale value immeasurably, can only be earned through satisfied customers. Word of mouth recommendations are becoming increasingly important for manufacturers today: full-page glossy adverts carry little weight if the people who actually sail the boats featured are left unimpressed.

A good reputation, which boosts resale value immeasurably, can only be earned through satisfied customers. Word of mouth recommendations are becoming increasingly important for manufacturers today: full-page glossy adverts carry little weight if the people who actually sail the boats featured are left unimpressed.

As for the special qualities of aluminium yachts, that is a subject to which I intend to return another time…

Peter Foerthmann

SV Berserk loss, commented by Nick Jaffe AUS

Nick Jaffe posted in his blog on 2nd of march 2011

Here is the article of 2nd of march 2011 published in NATIONAL STUFF.CO.NZ

SV Espen, Liz Cleere + Jamie Furlong UK

Oyster 435 with her owner Liz and Jamie on her way to MUMBAI, INDIA. Both are writing regularely for the British sailing magazin SAILING TODAY. Here are some interesting articles:

“SV ESPER to EGYPT” The intense blue waters and desert backdrops of the Red Sea have long been alluring to European sailors, but at a plrice. With fears of piracy and dangerous reefs at the forefront of their mind Liz Cleer and Jamie Furlong embarked on their trip from Turkey to Egypt with the secure framework of a cruising rally.

Here is their report about EGYPT – published in SAILING TODAY in September 2010 Egypt.09:10pdf

The report about Cruising Pirate Alley – published in SAILING TODAY in September 2010 Cruising PIrate Alley 09 : 10

The report about Sudan and Eritrea – published in SAILING TODAY in September 2010Sudan Eritrea 11:10

The report about the crossing of the Arabian Sea towards Mumbai – published in SAILING TODAY in March 2011Mumbai

If you want to follow Liz and Jamie´s adventures please visit their blog here

Sex sells – even in the marine industry!

I posted the following on the German yacht.de forum on 18 January, 2011 under the title “Sexy Sailing Blog, Around the world with an HR352”.

Once before I mentioned the story of a particular sailing couple and their search for a sponsor to help them with a windvane steering system so they didn’t have to stand at the helm or rely on an autopilot all the time:

“Last week it was the turn of a young and attractive Finnish lady with a lively blog who had fallen for a Spanish single-handed yachtsman at a party in Barcelona, moved into his bunk, suddenly considered herself a yachtswomen and – even more suddenly – decided it was time they sailed around the world. Her open and direct circular sent out to all vanegear manufacturers proffers media attention and exciting blogs with eye-catching photos and makes no secret of her criteria: “We have decided that saving money is important for us (especially now so close to departure!) and we will have to go for a brand that could offer us a greater discount”.

I find her willingness to cut straight to the chase disarming: it’s all about the money. Honest, credible … but somewhat wide of the mark as a pitch for sponsorship.”

Now the story continues. A few weeks later one of my fellow vanegear purveyors snapped up the bait – and Taru and her Alex had a new Sailomat system. Free gift? Generous discount? Hard-headed sponsorship deal on ruthless terms? Actually I don’t know the details: some things have to remain private even in our small world!

Now the story continues. A few weeks later one of my fellow vanegear purveyors snapped up the bait – and Taru and her Alex had a new Sailomat system. Free gift? Generous discount? Hard-headed sponsorship deal on ruthless terms? Actually I don’t know the details: some things have to remain private even in our small world!

And then all at once strange things began to happen: Neptune’s convert started calling her new deck hardware a Windpilot! What was I to do? Should I set her straight and put an end to the confusion? Or should I make like I hadn’t noticed and enjoy a little vicarious publicity?

After three months at sea, however, things have moved on, and what started out being called a Windpilot now answers to the name of Sailomat – albeit after a transitional phase revelling in the double-barrelled “Sailomat Windpilot”. So it looks as though I will not have to make that choice after all.

After three months at sea, however, things have moved on, and what started out being called a Windpilot now answers to the name of Sailomat – albeit after a transitional phase revelling in the double-barrelled “Sailomat Windpilot”. So it looks as though I will not have to make that choice after all.

I desired clarity, Taru desired a windvane, in fact desire is probably the common denominator of all the life/style/concepts scrambled together here. Is it really the adventure story that keeps drawing all those mouse fingers back to the Taru and Alex blog? Or is it rather a desire to see more of those sparkling images: fish whole fresh from the sea, fish on the table, fish raw and fish cooked – seasoned, perhaps, with the occasional modest glimpse of skin… Our sailing community, overwhelmingly male as it still is, finds the hook thus baited too enticing to refuse. Again and again: click, click, click.

Even without the mix-up over names, the heady combination of blogs, cuisine, sponsorship and bikini shots weaves a deeply tangled web: just who is paying the piper and whose tune is it anyway?

And is it really possible to turn clicks into money? Perhaps I’m still rather confused after all. But nonetheless happy enough not to lose any sleep worrying whether one might have got away. Plenty more fish in the sea I trust …

Peter Förthmann

SV Touch Wood, Sandra Kloesges + Michael Rinas GER

Zwei Rümpfe – Zwei Masten – Zwei Erwachsene – Zwei Kinder – und die weite Welt

Zwei Rümpfe – Zwei Masten – Zwei Erwachsene – Zwei Kinder – und die weite Welt

Im Frühjahr 2007 haben wir die fünf Jahre alte Wharram Tiki 38 von den Erbauern, Dave und Rita Barker gekauft. Mit sehr viel Liebe und Können entstand in einem Riesenzelt im Garten der Barkers in nur fünf Jahren Bauzeit ein hochseetüchtiger Katamaran.

Fünf Jahre lang lebten die beiden älteren Herrschaften danach in Portugal auf ihrem selbst gebauten Schmuckstück, bis sie entschieden, dass ein Apartment auf Dauer zum Leben komfortabler sei und dass Touch Wood außerdem gebaut wurde, um die Welt zu sehen.

Fünf Jahre lang lebten die beiden älteren Herrschaften danach in Portugal auf ihrem selbst gebauten Schmuckstück, bis sie entschieden, dass ein Apartment auf Dauer zum Leben komfortabler sei und dass Touch Wood außerdem gebaut wurde, um die Welt zu sehen.

Mit der Bitte, ihrem „Baby“ die Welt zu zeigen, verkauften Dave und Rita uns schweren Herzens ihr Schiff.

Mit der Bitte, ihrem „Baby“ die Welt zu zeigen, verkauften Dave und Rita uns schweren Herzens ihr Schiff.

Und hier beginnt eine neue Geschichte:

Hallo Peter Foerthmann,

viele Grüße aus Barbados. Wir haben gerade erfolgreich mit unserem Wharram Katamaran Touch Wood samt Kleinkind und Baby an Bord den Atlantik überquert. Das jüngste Crewmitglied, Quinn, hat auf dem Atlantik seinen ersten Geburtstag gefeiert. Ohne die extrem zuverlässige Steuerleistung unserer Windpilotanlage wäre dieses Unterfangen sicherlich sehr viel schwieriger, wenn nicht fast unmöglich gewesen. Sie hat uns trotz sehr hoher Wellen und einer zeitweilig starken Kreuzsee sicher auf Kurs gehalten.

Danke für diese supergute Windsteueranlage,

Sandra Kloesges

Hier geht´s weiter.

SV Morgi, Claudia+Edgar Schnetz GER

Französische ALBION 36, ein Stahlschiff der soliden Art. Auf 2 jähriger Rundreise vom Mittelmeer über die Kanaren zur Karibik und zurück haben der Skipper und seine Frau insgesamt 13353 sm zurückgelegt. Einziger Schaden in der gesamten Zeit;

Französische ALBION 36, ein Stahlschiff der soliden Art. Auf 2 jähriger Rundreise vom Mittelmeer über die Kanaren zur Karibik und zurück haben der Skipper und seine Frau insgesamt 13353 sm zurückgelegt. Einziger Schaden in der gesamten Zeit;

ein Block und die Membran der Dieselfoerderpumpe.

MORGI hat sich als Fahrtenschiff perfekt bewaehrt. Der Eigner: wir hatten immer das Gefuehl ein sehr sicheres Boot zu segeln. Hier geht´s zum blog

MORGI hat sich als Fahrtenschiff perfekt bewaehrt. Der Eigner: wir hatten immer das Gefuehl ein sehr sicheres Boot zu segeln. Hier geht´s zum blog

Dream and reality

Seglers Träume sind alle gleich:

Seglers Träume sind alle gleich:

Palmen, Sonne, Wärme, Wind und Wellen –

eine Umgebung, die uns den Alltag vergessen lässt – dummerweise sind das Ländereien, die nicht vor der Haustür liegen – zu denen man fliegen – oder langwierig segeln muss – bevor man den Anker dann – in den Sand eingraben kann.

Dagegen ist die Wirklichkeit eine andere Sache – Segeln findet nur in den Träumen statt – und auch der Versuch – an Land dem Winterlager einfach wegzusegeln – kann nicht gelingen – wenn das Schiff von anderen daran gehindert ist.

Dagegen ist die Wirklichkeit eine andere Sache – Segeln findet nur in den Träumen statt – und auch der Versuch – an Land dem Winterlager einfach wegzusegeln – kann nicht gelingen – wenn das Schiff von anderen daran gehindert ist.

So helfen nur die schönen Geschichten, vom Segeln mit den zwei Geliebten – dem Schiff an der einen und der Frau an der anderen Seite – wer die Erste nicht zur Verfügung hat – dem hilft die Bank – bei der Zweiten – vielleicht – eine Pause auf der Lügenbank.

So helfen nur die schönen Geschichten, vom Segeln mit den zwei Geliebten – dem Schiff an der einen und der Frau an der anderen Seite – wer die Erste nicht zur Verfügung hat – dem hilft die Bank – bei der Zweiten – vielleicht – eine Pause auf der Lügenbank.

Peter Foerthmann

SV Papalagi, Michael Ballhouse GER

Sparkman & Stevens 35 Stahlbau der soliden Art – für kernige Anlegemanöver bestens vorbereitet.

Sparkman & Stevens 35 Stahlbau der soliden Art – für kernige Anlegemanöver bestens vorbereitet.

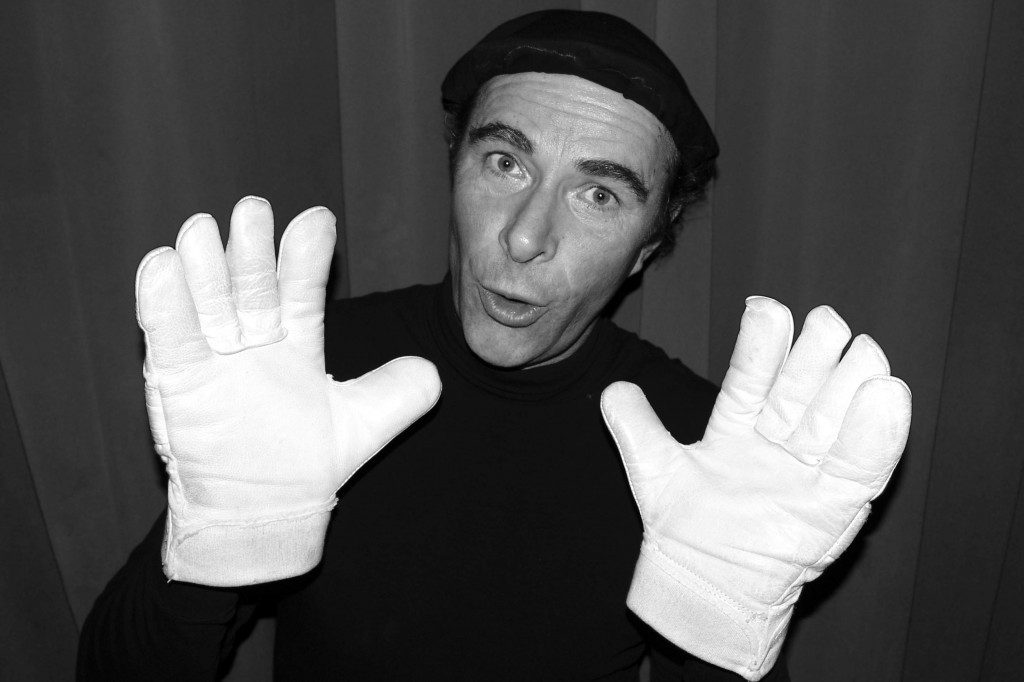

Eigner, Skipper, Pantomime, Conferencier und Allein Unterhalter Mick lebt in Hamburg und nordeuropäischen Küsten Gewässern auf seinem Schiff, das immer mal wieder woanders angebunden ist.

Eigner, Skipper, Pantomime, Conferencier und Allein Unterhalter Mick lebt in Hamburg und nordeuropäischen Küsten Gewässern auf seinem Schiff, das immer mal wieder woanders angebunden ist.

Das Schiff ist ein Mikrokosmos ganz besonderer Art, es wird alternativ mit Kohle, Holz und anderen – gesetzlich erlaubten – brennbaren Gegenständen im Winter warm beheizt – es verfügt über Werkzeuge, Töpfe und andere Kuriositäten, mit denen der Skipper sich und sein Schiff auch in schwierigen Situationen überall verteidigen oder befreien kann.

Das Schiff ist ein Mikrokosmos ganz besonderer Art, es wird alternativ mit Kohle, Holz und anderen – gesetzlich erlaubten – brennbaren Gegenständen im Winter warm beheizt – es verfügt über Werkzeuge, Töpfe und andere Kuriositäten, mit denen der Skipper sich und sein Schiff auch in schwierigen Situationen überall verteidigen oder befreien kann.

Und auch ein Schaf ist stets an Bord, zumindest das Fell, das den Eigner wärmen kann. Nordsee ist Mordsee – das ist des Skippers Lieblings Wasserkessel – dort kreuzt er zwischen Kelten, Kaltem Westen und Wikingern hin und her – wo immer sein Impressario – also er selbst – ihn hinbeordert oder abkommandiert.

Und auch ein Schaf ist stets an Bord, zumindest das Fell, das den Eigner wärmen kann. Nordsee ist Mordsee – das ist des Skippers Lieblings Wasserkessel – dort kreuzt er zwischen Kelten, Kaltem Westen und Wikingern hin und her – wo immer sein Impressario – also er selbst – ihn hinbeordert oder abkommandiert.

Mick betreibt ein Künstler Portal der besonderen Sorte: seine Facebook Seite “Michael Ballhouse” und das Label “Ballhouse United Artists” vernetzt gleichgesinnte Musiker, Künstler und Interpreten rund um die Lebens Kugel. Seine Fan-Gemeinde könnte einen Ocean Riesen zum Kentern bringen. Für sie schreibt Mick zudem ein Buch:

Mick betreibt ein Künstler Portal der besonderen Sorte: seine Facebook Seite “Michael Ballhouse” und das Label “Ballhouse United Artists” vernetzt gleichgesinnte Musiker, Künstler und Interpreten rund um die Lebens Kugel. Seine Fan-Gemeinde könnte einen Ocean Riesen zum Kentern bringen. Für sie schreibt Mick zudem ein Buch:

„bukka bukka facebook.me“ by Mick M.

Comedy Mime / Master Flash Dancer / Moderator / Humorist. Winner of the GOLDEN CAMERA in France ( Les Cameras d`or ) First Pantomime that can speak and Haiku Rap MICKrophon Poetry

Mick M. > Socializer Export / Profi Kavalier

People Power Entertainment and Live Music

The Musicality of Movement …. update me for stabil Humor – Hier sein Link

SY Sumara of Weymouth, Alasdair Flint UK

Email change with an obedient yachtsmen:

Email change with an obedient yachtsmen:

Hi Peter,

After 13 years of hard work my Windpilot is now in need of some tender loving care. Some of the teeth have stripped from the nylon turning gear and the whole unit has become rather wobbly. Do you offer a complete service if I were to return it to you or should I order the damaged parts and attempt to service it myself. Do you have a spares diagram?

Best regards,

Alasdair

Dear Alasdair,

unit got tender love, has been disassembled and assembled back again and getting cleaned from lot of Lanolin everywhere – even at places it should not be.

PLEASE be not attempted to use Lanolin for greasing purposes in future times because this will prohibit sentitive operation in light airs.

Kind regards from Hamburg – and always just a mouseclick away

Peter