DEVICES AND BACKUPS – THE SHORT VERSION

Sailing is great, especially when the bow is pointed towards those gently swaying palms. What a pity it is that the trees of our nautical fantasies – and the hula girls dancing beneath them (yes I know they only shake their hips for visitors when the Tourist Office tells them to) – are so ridiculously far away. Bluewater sailing has a definite mystique all its own and so many of the destinations it opens up are the stuff of dreams. Might this explain why a good many sailors who have thought about the possibility of a round the world trip even once end up calling that thought a plan and sharing it with their social circle as soon as possible?

Sailing is great, especially when the bow is pointed towards those gently swaying palms. What a pity it is that the trees of our nautical fantasies – and the hula girls dancing beneath them (yes I know they only shake their hips for visitors when the Tourist Office tells them to) – are so ridiculously far away. Bluewater sailing has a definite mystique all its own and so many of the destinations it opens up are the stuff of dreams. Might this explain why a good many sailors who have thought about the possibility of a round the world trip even once end up calling that thought a plan and sharing it with their social circle as soon as possible?

Dreaming big in public can be a way to gain a little separation from the herd, you understand – and the consequences of ultimately failing to walk the walk lie so far in the future that they can virtually be discounted altogether, no? And even when the chickens do come home to roost, the magic of social media makes it possible to massage and optimise any story until the reflection staring back from the mirror becomes tolerable again. The golden rule endures: never waste an opportunity put one over on the competition!

Steering can sometimes be far from great. Enthusiasm for the helm tends to be inversely proportional to length of voyage. Posing at the controls is great for photos – look at me, master of the universe – but who would want to be chained there once land and audience have receded? Commercial shipping plies the oceans under automatic control after all, aided by other electronic devices that help keep the behemoths a safe distance from each other. Do I mean “aided by” or should that be “reliant on”? Switching off the AIS (for whatever dubious reason) anywhere near traffic is asking – begging, no less – for trouble. And if something does go crunch in the night? What then? Cautiously consult the insurance or put it down to possibly having fallen asleep and take it on the chin? Do we really want to delve into the causes? Knowing nothing can be most advantageous sometimes, because that way the insurance will probably pay out faster, right? Nobody wants to be left without a chair when the music stops; nobody wants to be the fall guy.

Steering can sometimes be far from great. Enthusiasm for the helm tends to be inversely proportional to length of voyage. Posing at the controls is great for photos – look at me, master of the universe – but who would want to be chained there once land and audience have receded? Commercial shipping plies the oceans under automatic control after all, aided by other electronic devices that help keep the behemoths a safe distance from each other. Do I mean “aided by” or should that be “reliant on”? Switching off the AIS (for whatever dubious reason) anywhere near traffic is asking – begging, no less – for trouble. And if something does go crunch in the night? What then? Cautiously consult the insurance or put it down to possibly having fallen asleep and take it on the chin? Do we really want to delve into the causes? Knowing nothing can be most advantageous sometimes, because that way the insurance will probably pay out faster, right? Nobody wants to be left without a chair when the music stops; nobody wants to be the fall guy.

Some weighty tomes have been written about how to avoid the chore of steering by hand on sailing boats (including, I confess, by me). Brevity has unmistakable advantages though and this time I intend to keep it short. There are three devices available and it amazes me that after almost half a century, there are still some sailors around trying to bend reality to fit their own preconceptions even though the laws of physics, hewn in stone as they are, should surely have penetrated every last skull by now. Reading around, it appears we might be due a little refresher course. So here it is.

Some weighty tomes have been written about how to avoid the chore of steering by hand on sailing boats (including, I confess, by me). Brevity has unmistakable advantages though and this time I intend to keep it short. There are three devices available and it amazes me that after almost half a century, there are still some sailors around trying to bend reality to fit their own preconceptions even though the laws of physics, hewn in stone as they are, should surely have penetrated every last skull by now. Reading around, it appears we might be due a little refresher course. So here it is.

The three devices (and backups) are easily summarised:

The three devices (and backups) are easily summarised:

– The human hand is the best, at least until the eyes that guide it start to close. Steering is tiring and sometimes tiresome work for human crew and the fun factor is likely to drop off significantly, potentially bringing the whole adventure to a premature end, if the supply of willing and able bodies runs out with no alternative solution available.

– The autopilot has an established place on yachts, be it on or below deck. The noise, risks and compromises associated with these inscrutable electronic assistants have been widely reported. As tends to be the case with black-box systems, everything is fine until it isn’t (a realisation some may well find unhelpful for their peace of mind).

– The Windpilot (they also go by other names) slaves away in silence borrowing just a fraction more of that free energy the boat is already converting into forward progress. Who could ask for more?

The question, then, is how to choose (and the selection criteria will sound rather familiar to regular readers). The human element is important, but for brain rather than brawn. I have always found it interesting (and it is still the case and I still find it interesting) that almost everyone who comes to me for a transom ornament already has an electronic steering slave on the books. What does this observation tell us? Must I really explain it again? I think not. I should though take this opportunity to point out that a small electric autopilot can operate the transom ornament very effectively in a flat calm. Double redundancy: The advantages speak for themselves!

Many sailors, having finally found the best way to share duties between the different options, wonder how it can possibly have taken them so long. And cost them so much. The blame, I would suggest, lies with marketing and with the amount invested in advertising designed to find and operate the “go electric and go large” push button in the sailor’s brain. Myself, I prefer to trust sailors to figure it out for themselves. I put no end of information and examples out there but am content to leave first contact until that initial e-mail lands in my inbox. None of this is news, of course, so instead of raking over old ground again I thought I might add some spice to the mix for all those who always seem to (think they) know better.

The first autopilot for commercial shipping came into the world at about the same time as I did, which is quite a while back now (data protection concerns and the risk of scaring myself prevent me being any more precise).

The first transom ornament for sailing boats was invented about 20 years later, which is also when the first little electric autopilot for yachts appeared. Was it simply a question of technological progress or was it only then that sailors became too lazy to steer and/or realised how good for the soul it was to have a little nap in the fresh air while the boat crept its way across the water?

Sailors often seem to assume that the autopilots used on pleasure craft offer a level of reliability similar to that of those used in commercial shipping. The fact is they do not – and the differences are substantial.

Sailors often seem to assume that the autopilots used on pleasure craft offer a level of reliability similar to that of those used in commercial shipping. The fact is they do not – and the differences are substantial.

Ships that have to pay their way at sea always have generators operating constantly, so they are never short of electricity and since automatic steering is cheaper in the long run than several watches’ worth of human crew, shipping lines can afford to have robust and fully integrated units installed during construction. Commercial vessels rely heavily on hydraulic systems anyway, so adding a few more circuits for steering is no big deal. Everything necessary for reliable hands-free steering is present in abundance, in other words.

Ships that have to pay their way at sea always have generators operating constantly, so they are never short of electricity and since automatic steering is cheaper in the long run than several watches’ worth of human crew, shipping lines can afford to have robust and fully integrated units installed during construction. Commercial vessels rely heavily on hydraulic systems anyway, so adding a few more circuits for steering is no big deal. Everything necessary for reliable hands-free steering is present in abundance, in other words.

The same cannot be said of sailing yachts, on which electricity is always in short supply. Battery life can be extended somewhat using “intelligent” (as the manufacturers like to call it) software to restrain the autopilot from responding to every single miniscule deviation from course, but the fundamental problem remains. As (almost?) all sailors know only too well, electricity is generally a scarce commodity on board and none of the electrical systems will work properly once the voltage drops below a certain level.

The same cannot be said of sailing yachts, on which electricity is always in short supply. Battery life can be extended somewhat using “intelligent” (as the manufacturers like to call it) software to restrain the autopilot from responding to every single miniscule deviation from course, but the fundamental problem remains. As (almost?) all sailors know only too well, electricity is generally a scarce commodity on board and none of the electrical systems will work properly once the voltage drops below a certain level.

A LOADED QUESTION Have you ever seen a car gearbox with plastic gears? That would almost certainly be a no, unless you are thinking of scale models.

A LOADED QUESTION Have you ever seen a car gearbox with plastic gears? That would almost certainly be a no, unless you are thinking of scale models.

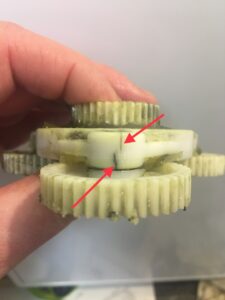

If you happened to be someone who enjoys disassembling autopilots, however, you probably would have seen plenty of plastic gears. Believe it or not, a large proportion of the autopilot units designed for pleasure craft contain gears made from POM or other plastics. These are components whose job is to transmit the force produced by an electric motor to a fairly substantial rudder. There is no form of damping in the system either, so the mechanism also has to withstand all the shock loads generated through the rudder by waves and sea state.

If you happened to be someone who enjoys disassembling autopilots, however, you probably would have seen plenty of plastic gears. Believe it or not, a large proportion of the autopilot units designed for pleasure craft contain gears made from POM or other plastics. These are components whose job is to transmit the force produced by an electric motor to a fairly substantial rudder. There is no form of damping in the system either, so the mechanism also has to withstand all the shock loads generated through the rudder by waves and sea state.

An experienced skipper – or for that matter a servo-pendulum windvane self-steering system – steers with a soft touch, adjusting course smoothly in time with the rhythm of wind and water. An electric autopilot of any type, in contrast, is rigidly connected to the main rudder, so rudder, bearings and the autopilot motor are exposed in abrupt fashion to the full force of every movement initiated at either end of the system. It seems logical to conclude this will place significantly greater strain on the rudder than a solution with inbuilt damping. Whether the stresses involved are substantial enough to cause problems for boats with a spade rudder, which has only two, closely spaced bearings is a question I will leave for skippers contemplating using this type of boat on long passages to answer. I wonder too whether the autopilot companies actually specify an expected service life in their design and manufacturing processes. A failure due to material fatigue could have very serious consequences on a bluewater yacht far from land.

I remember being in Les Sables d´Olonne some decades ago as the solo sailing heroes preparing for their non-stop blast around the world were loading spare autopilots by the dozen. They probably all had plastic gearbox components at first but I understand Autohelm quickly upgraded its GP Series to brass for improved durability. Stalking electric autopilot designers to find out what materials they use in their gearboxes these days is not my style, but I am always listening out for reports of sailors’ experiences on the high seas to add to my mental database. Life-long students of self-steering (and who isn’t?) know that every day brings new lessons and insights, especially regarding those purported all-rounders to which so many sailors (who have not yet been dragged from their bunk on a cold wet night when computer says no) are apparently so happy to entrust their comfort and safety.

Read on for a selection of recent reports from the field that have helped to inform my thinking on the subject.

Douwe Gorter SV Boer, schrieb kürzlich:

Douwe Gorter SV Boer, schrieb kürzlich:

I have restored BØR, the Bestevaer 53. And we have sailed to Portugal/ Portimao. Where I have secured a berth for the coming years as a “base”. We used the Windpilot all the from the Netherlands via south England because the Whitlock drive broke and Lewmar had a hard time to deliver the new one. The WP performed very well in the Biskay with considerable waves and winds up to 45 knots. I was really happy because steering a 53 ft 20tons yacht in that sea was exhausting but the WP didn’t complain.

Jens Borner had a summer of steering for himself on his Bavaria 40 Skokie in 2023 having spent many months over the winter upgrading the boat’s electrical system with the latest LiPo technology (including magic batteries and a power management unit clever enough to drag him out of his bed ashore in the middle of the night – via an alert on his mobile phone – whenever anything in the system misbehaved). More than once he had to race down to the coast at an unthinkable hour to cool everything down – including his own frazzled nerves. Here’s what Jens had to say:

Jens Borner had a summer of steering for himself on his Bavaria 40 Skokie in 2023 having spent many months over the winter upgrading the boat’s electrical system with the latest LiPo technology (including magic batteries and a power management unit clever enough to drag him out of his bed ashore in the middle of the night – via an alert on his mobile phone – whenever anything in the system misbehaved). More than once he had to race down to the coast at an unthinkable hour to cool everything down – including his own frazzled nerves. Here’s what Jens had to say:

Hi Peter,

It’s great to see how, as well as providing so much useful information, this site helps to make sure new owners understand what equipment they really need.

What persuaded me to leave a comment here is the part in Douwe Gorter’s letter that says, “…because the Whitlock drive broke and Lewmar had a hard time to deliver the new one.”

I recently had a similarly joyous experience of Lewmar England’s customer service.

I recently had a similarly joyous experience of Lewmar England’s customer service.

Our boat has a Lewmar electric drive for automatic steering. I decided it must be time to service the geared motor last winter after noticing that it was becoming very noisy. On dismantling the drive, I discovered a plastic epicyclic gear train with obvious cracks in the planet gear axial bearings. Having seen photos in the past of plastic gear trains that had disintegrated completely, I thought I had better replace the damaged components straight away and tried to contact Lewmar in England to order the new parts. Neither phone calls nor e-mails produced any response, so I tried talking to Lewmar in Germany instead. I managed to meet a Lewmar representative in person at a boat show in January 2023, at which point I was informed that individual replacement parts were not available but that they could sell me a set including chain, pinion gear, the complete geared motor, the welded steel housing and the screws to fit it all – for about the same price as a second-hand car.

Our boat has a Lewmar electric drive for automatic steering. I decided it must be time to service the geared motor last winter after noticing that it was becoming very noisy. On dismantling the drive, I discovered a plastic epicyclic gear train with obvious cracks in the planet gear axial bearings. Having seen photos in the past of plastic gear trains that had disintegrated completely, I thought I had better replace the damaged components straight away and tried to contact Lewmar in England to order the new parts. Neither phone calls nor e-mails produced any response, so I tried talking to Lewmar in Germany instead. I managed to meet a Lewmar representative in person at a boat show in January 2023, at which point I was informed that individual replacement parts were not available but that they could sell me a set including chain, pinion gear, the complete geared motor, the welded steel housing and the screws to fit it all – for about the same price as a second-hand car.

Money for a load of parts I didn’t need, in other words, but the choice was all or nothing. Having negotiated a boat show discount, I placed my order for the complete set on 13 February 2023 and started waiting. No fewer than 15 weeks later – well into the second half of May – my delivery arrived. Fortunately that still left me enough time to finish the repair before our long summer cruise. Unfortunately the drive had not been packaged properly for shipping and was damaged, with nasty scratches and deep dents in the aluminium as well as scuffed paintwork. I made a complaint, received some money back and fixed the damage myself.

There was another surprise still to come though: when I installed the new drive and tried it out, it did not sound happy at all. The noises reminded me of something you might hear coming from a sickly horse. I made another complaint, took the drive out again and handed it over to Lewmar’s field service to be repaired under warranty.

Money for a load of parts I didn’t need, in other words, but the choice was all or nothing. Having negotiated a boat show discount, I placed my order for the complete set on 13 February 2023 and started waiting. No fewer than 15 weeks later – well into the second half of May – my delivery arrived. Fortunately that still left me enough time to finish the repair before our long summer cruise. Unfortunately the drive had not been packaged properly for shipping and was damaged, with nasty scratches and deep dents in the aluminium as well as scuffed paintwork. I made a complaint, received some money back and fixed the damage myself.

There was another surprise still to come though: when I installed the new drive and tried it out, it did not sound happy at all. The noises reminded me of something you might hear coming from a sickly horse. I made another complaint, took the drive out again and handed it over to Lewmar’s field service to be repaired under warranty.

I have contacted them by phone several times and by e-mail any number of times over the last four months and the response has always been the same: “We don’t know where the drive is and cannot say when you might have it back.” We consequently spent the four months of our summer cruise through Scandinavia steering by hand and hoping the drive might be along to join us soon. Crumbs of new information – “The order number wasn’t issued properly, so nothing was done with the drive” and “It should be ready by now and just needs to be shipped” – raised our hopes and eventually we were told we would have the drive in three weeks. Three weeks came and went with no progress and we were back to nobody knowing when it might appear. There was no way of knowing or finding out.

I have contacted them by phone several times and by e-mail any number of times over the last four months and the response has always been the same: “We don’t know where the drive is and cannot say when you might have it back.” We consequently spent the four months of our summer cruise through Scandinavia steering by hand and hoping the drive might be along to join us soon. Crumbs of new information – “The order number wasn’t issued properly, so nothing was done with the drive” and “It should be ready by now and just needs to be shipped” – raised our hopes and eventually we were told we would have the drive in three weeks. Three weeks came and went with no progress and we were back to nobody knowing when it might appear. There was no way of knowing or finding out.

We have been waiting for our electric autopilot drive since 19 June – that’s 16 weeks, four whole months now – and we are still waiting.

Why the blow-by-blow account? Because I remember reading an article here on the Windpilot blog about the suggestion that windvane self-steering system technology was antiquated compared to electric autopilots.

We have been waiting for our electric autopilot drive since 19 June – that’s 16 weeks, four whole months now – and we are still waiting.

Why the blow-by-blow account? Because I remember reading an article here on the Windpilot blog about the suggestion that windvane self-steering system technology was antiquated compared to electric autopilots.

When thinking about who to trust with their steering duties on passage, sailors really need to consider not just the technology itself but also the customer service and people behind the product. I know that I would never have had to deal with this sort of nonsense with Windpilot. E-mails are answered within a few hours and everyone receives the replacement part they need in no time at all. Wherever they are in the world. With no ifs or buts. And with tips for installation and operation thrown in for free. Personal support!

Imagine a boat somewhere out in the Pacific having to go through what we have experienced. Eight months stuck on some atoll?

Lewmar, have a look at Hamburg and see how it should be done!

Regards,

Jens Borner

These recent reports in Yachting World about the experiences of sailors on the latest ARC are also worth a read.

Seventy-five boats reported problems with their autopilots, 56 of which were encountered on the ocean crossing (rather than the ‘shakedown’ sail to Las Palmas from mainland Europe). Digging into the details of those problems reveals that skippers demand perfection but will still cede control to the unit even if performance levels drop significantly.

Drive unit problems made up 45% of the issues encountered – that’s 25 drive units across the fleet that were deemed unsatisfactory by over 250 transatlantic skippers. Just over 20% of problems were traced back to the course computer or the control unit, which leaves 30% (approximately) of problems in the ‘don’t know category’.

Problems and solutions

Many skippers gave their self-steering equipment quite high ratings and then went on to raise multiple issues with the overall performance or installation or reliability of their set-ups. It makes for an interesting read, and leads us to conclude that for most skippers even a poorly functioning self-steering system is better than nothing.

We discovered multiple references to autopilots as people, or crewmembers with foibles and idiosyncrasies: The skipper of Amandla Kulu advises feeding the autopilot coffee and biscuits, while the German skipper of Petoya Too described his Hydrovane as: ‘a full crew who needs no food – happy with it all the time.’

Not all windvane systems were quite so highly rated. The skipper of Malouine made a positive report on the yacht’s self-steering: ‘She is doing a good job, but takes a lot of energy, so we prefer using the Windpilot’ – which is typical praise of ‘free’ self-steering windvane systems over previous ARCs. They averaged eight hours per day on autopilot, stating: ‘we turned off the autopilot in squalls/strong winds so that it lasts for longer and has less wear and tear.’

They relied instead on a 30+ year old Windpilot for up to 10 hours per day, but even that wasn’t smooth sailing all the time: ‘Working unless the wind is coming directly from behind, then she zigzags and too big waves make her steer off course.’

The 2011 UK-flagged Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 45DS Optimistic was another of the belt-and-braces boats with autopilot and windvane on board. The boat’s hydraulic drive unit, computers and sensors worked perfectly for 22 hours per day on the crossing (via Cape Verdes), but the skipper reported problems with the Hydrovane instead: ‘The Hydrovane rudder broke on day two of leg one. It was repaired in Cape Verde then snapped in half on day two of leg two.’ His verdict: ‘Hydrovane did everything in their power to help me out in this situation. Their support and customer service has been very good,’ yet he concluded: the Hydrovane ‘cannot cope with big waves’. His top three tips for self-sufficiency: ‘1. conservative sail plan at night 2. good preparation 3. good tools and spares.’

Usually, windvanes take over the steering when/if autopilots fail. However there was another UK-flagged large monohull for which the opposite was true. Paul Cook, skipper of Esti, a 1996 Moody 44, was very impressed with his recently installed Raymarine ACU-400 with hydraulic ram. ‘It saved us and performed perfectly. We found the “wind vane” mode to be perfect for optimising wind shifts,’ he said. So although he didn’t need to rely on the failed windvane rudder, he pointed out that without it he’d lost his main emergency steering system.

Autopilots aren’t without their share of faults though. South African skipper Darrol Martin took part in the ARC Plus aboard his 1988 Amel Mango. He and his crew took apart their Raymarine rotary drive unit multiple times en route to Las Palmas as well as once during the ocean passage. Despite a professional installation less than four months before the start of the event, Martin reported that the drive gears were ‘mismatched’ and the screws were too small and ‘not strong enough to hold’.

On passage to Mindelo, they made repairs using spare ring gears and planetary gears bought in Las Palmas and reported: ‘After 4th repair, it worked perfectly for 2nd half of the crossing.’ This was followed up by some further advice: ‘Get a windvane as backup. Autopilot is not robust.’

Thirty boats crossed the startline for the ARC January, including skipper Paolo Santagiuliana aboard his virtually brand new Neel 51 trimaran Chica 3. The boat was fitted with the Zeus 3 chartplotter/multifunction display, which he rated 4 out of 5, but Santagiuliana found that the sensors feeding the data to his B&G drive unit via a H5000 CPU resulted in ‘very frequent ROUTE OFF’ messages. He rated the pilot’s performance as ‘very poor’ in the second half of the crossing and lamented not bringing spare sensors, but he had made provisions for such a failure by fitting a second autopilot.

‘We arrived thanks to the second one. The limit of the second one is that it cannot be fully interfaced with the B&G Zeus so you can’t automatically follow the wind, you have to manually modify the route.’ The H5000 has now been recalibrated: ‘narrowing the value of rudder gain, auto trim and counter rudder that were too large, generating a wide variation of route when the wave was more than 2-3m. I have to say that the software is much less easy for a normal sailor used to other brands.’

Andreas Müller’s story about repairing on old Raymarine autopilot for his boat Rio deserves a look too (and he is keen that other sailors should follow his successful low-cost approach).

Andreas Müller’s story about repairing on old Raymarine autopilot for his boat Rio deserves a look too (and he is keen that other sailors should follow his successful low-cost approach).

Let me clarify one thing. These lines should not be understood – or even worse dismissed – as a marketing effort by a confused and increasingly grey-haired manufacturer of transom ornaments fearful for the future of his livelihood. My concern is that as electronic devices become more and more ubiquitous on land, sailors are losing sight of the “keep it simple, stupid” principle that has always served us so well at sea. Murphy has a long reach coupled with infinite patience and we have no more chance of outrunning his law than we do the laws of physics. This is the wisdom of old age, acquired first-hand, assures

Peter Foerthmann

8 October 2023